One of the most persistent myths in American culture is that our family surnames were changed at Ellis Island. Just how ingrained is this myth? Well, when my younger two children were in 5th grade, their school included an Ellis Island simulation as part of a learning module on immigration. After learning about the “great American melting pot,” the economic and social factors that prompted immigration, and some of the contributions and impact that immigrants had on American society, the students capped off the unit with an Ellis Island Day immigration simulation. Prior to the simulation, students were assigned names and identities (hypothetical, not historical) of various”immigrants” from the late 19th century. They created costumes that would have been typical for their assigned immigrants and when Ellis Island Day came, these “immigrants” were “processed” by teachers and parent volunteers posing as immigration officials. Processing stations included mock health inspections and checking of documents, and at one station, parent volunteers were instructed to inform some of the “immigrants” that their names were “too foreign-sounding” so, “we’ll call you Mary Smith from now on.”

Although I applaud the idea of an immigration learning module and think that the Ellis Island Day simulation is a fun way for the kids to experience what the process might have been like, I found this particular element of the simulation to be appalling since it reinforces the very myth that so many of us genealogists have tried to dispel. When I attempted to explain this to the teacher, and then to the school administration, I was told, “You’re arguing with History.”

Really?

One of my favorite articles that debunks the Ellis Island Name Change myth is this one,1 and one of my favorite passages from that article is this:

The idea that names were changed at Ellis Island raises lots of questions. For instance, if names were changed, what happened to the paperwork? And if inspectors were charged with changing names, why are there no records of this? Where are the lists of approved names? Where are the first hand accounts, of inspectors and immigrants? If immigrants had name changes forced upon them, why did they not simply change their name back when they entered the country? Or, if they could not, where is paperwork describing the roles of Federal officials charged with making sure that names were not changed back?

It underscores the lack of thought that goes into the knee-jerk assertion about those name changes. The myth of Ellis Island is so easily accepted that most people don’t bother to consider the implications, but if one takes a moment to do that, the myth quickly falls apart.

So what really happened? How did we end up with so many distorted, truncated, or translated versions of our immigrant ancestors’ surnames? Here’s one example from my own family history.

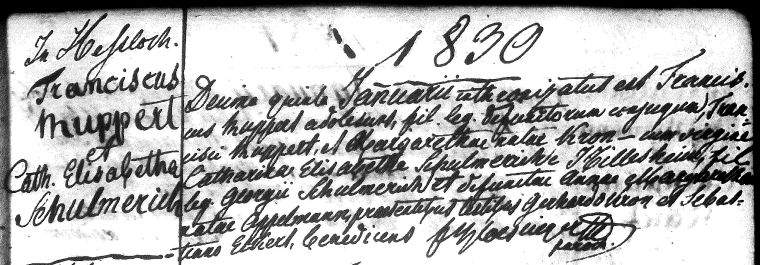

My maiden name, Roberts, was originally Ruppert. My immigrant ancestors were the family of Franz and Catherina Elisabeth (née Schulmerich) Ruppert, who were married in the little village of Heßloch in 1830, in what was at the time the Grand Duchy of Hesse, colloquially known as Hesse-Darmstadt (Figure 1):

Figure 1: Marriage record from the Roman Catholic parish in Heßloch for Franciscus Ruppert and Catharina Elisabetha Schulmerich, 15 January 1830.2 Translation: “On the 15th day of January is married Franz Ruppert, young man, legitimate son of the late spouses Franz Ruppert and Margaretha née Kron — with the young woman Catharina Elisabeth Schulmerich of Hillesheim, legitimate daughter of Georg Schulmerich and the late Anna Margaretha née Appelmann, in the presence of witnesses Gerhard Kron and Sebastian Eckert, blessed by Fr. [illegible]”

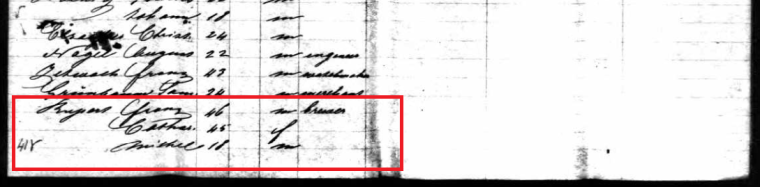

The Ruppert family included their three sons, Johann Georg, Michael, and Arnold, as well as daughter Catherina Susannah. Michael was my great-great-great-grandfather. In 1851, Georg traveled to the U.S.,3 followed by the rest of the family in 1853.4 Their passenger manifest is shown below (Figures 2a and 2b).

Figure 2a: Passenger manifest from the William Tell, arriving on 4 March 1853, showing parents Franz and Catherine and son Michael Ruppert.

Figure 2b: Passenger manifest from the William Tell, arriving on 4 March 1853, showing Franz and Catherine Ruppert’s children, Arnold and Catherine Ruppert.

To me, the name looks like it’s written as “Rupert,” although the transcriber at Ancestry indexed it as “Rupard.” The ages of the family members agree well with their ages based on their baptismal records from Germany. The manifest is not especially informative, which is typical for earlier manifests like this, mentioning only that their place of origin was Württemberg, their destination was the United States, and Franz’s occupation was a brewer.

One might argue that my family surname clearly wasn’t changed at Ellis Island because in the case of my Rupperts, they didn’t enter the U.S. through Ellis Island at all. The Ellis Island inspection station didn’t open until 1892, and its predecessor, Castle Garden, did not open until 1855. In the first half of the 19th century, when the Rupperts came over, immigrants merely landed at docks around South Street in Manhattan. However, I’m willing to bet that the vast majority of people who purport that their family names were changed at “Ellis Island” probably have no idea at which port or on what date their immigrant ancestors actually arrived in the U.S. When it comes to the myth, the main idea seems to be that the name change resulted from something the immigrants were told by someone in an official capacity when they entered the U.S.

So, my ancestors were Ruppert in Germany, and a reasonable misspelling thereof was recorded on their passenger manifest. What happened in the U.S.?

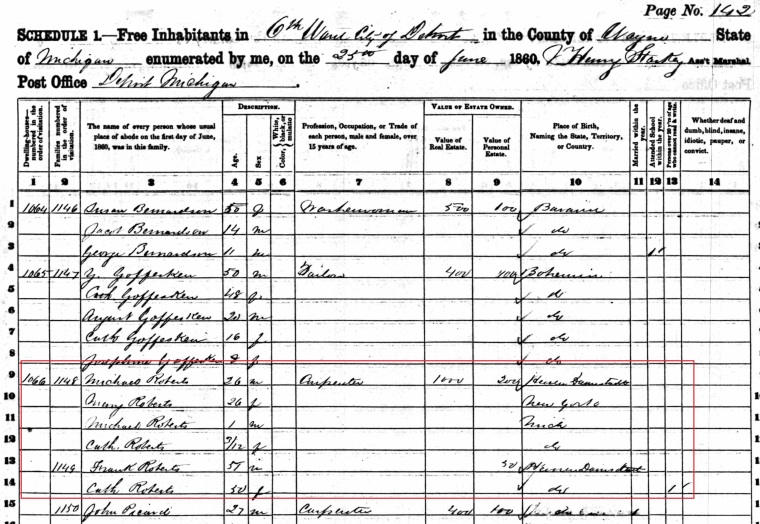

By 1860, the family had settled in Detroit, Michigan and had already begun using the name Roberts, as evident from the 1860 U.S. Census (Figure 3).5

Figure 3: Excerpt from the 1860 U.S. Census for Detroit, Michigan, showing the Michael Roberts and Frank Roberts households.

The first part of the Roberts family is the family of Michael and Mary (also known as Maria Magdalena) Roberts, with their children Michael and Catherine. Below them are the elder Michael’s parents, Frank and Catherine. The younger Michael, also known as Michael Frank, also known as Frank Michael, was my great-great-grandfather.

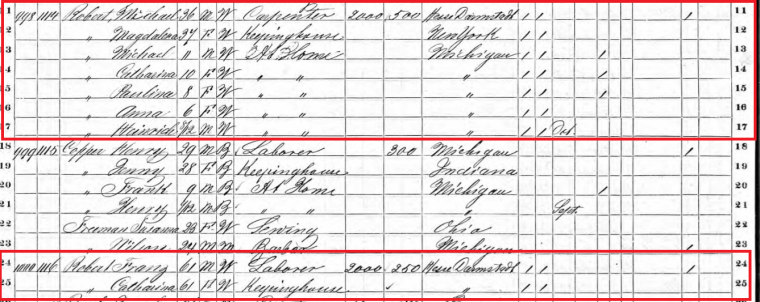

As anyone who has ever done genealogy for more than five minutes can tell you, names were pretty fluid up until, say, the 1930s. So in 1870, the family surname was recorded as Robert (Figure 4).6

Figure 4: Excerpt from the 1870 U.S. Census for Detroit, Michigan, showing the Michael Robert and Franz Robert households.

In this census, we see that Michael “Robert” was still employed as a carpenter and that two more children had been born to the family, daughters Paulina and Anna and a son, Heinrich. Michael’s wife Mary’s name appears here as Magdalena. Michael’s parents, Frank and Catherine Robert were still living nearby, and the fact that their name was also recorded as “Robert” and not “Roberts” suggests that this was a version of the surname that the family was collectively trying out at that time, rather than simply a recording error on the part of the census-taker. Frank was also recorded as Franz once again.

By 1880, Franz and Catherine were living on Prospect Street and were continuing to use the surname Robert, although Franz was recorded as Frank once again, as shown in Figure 5.7

Figure 5: Excerpt from the 1880 U.S. Census for Detroit, Michigan, showing Frank Robert family.

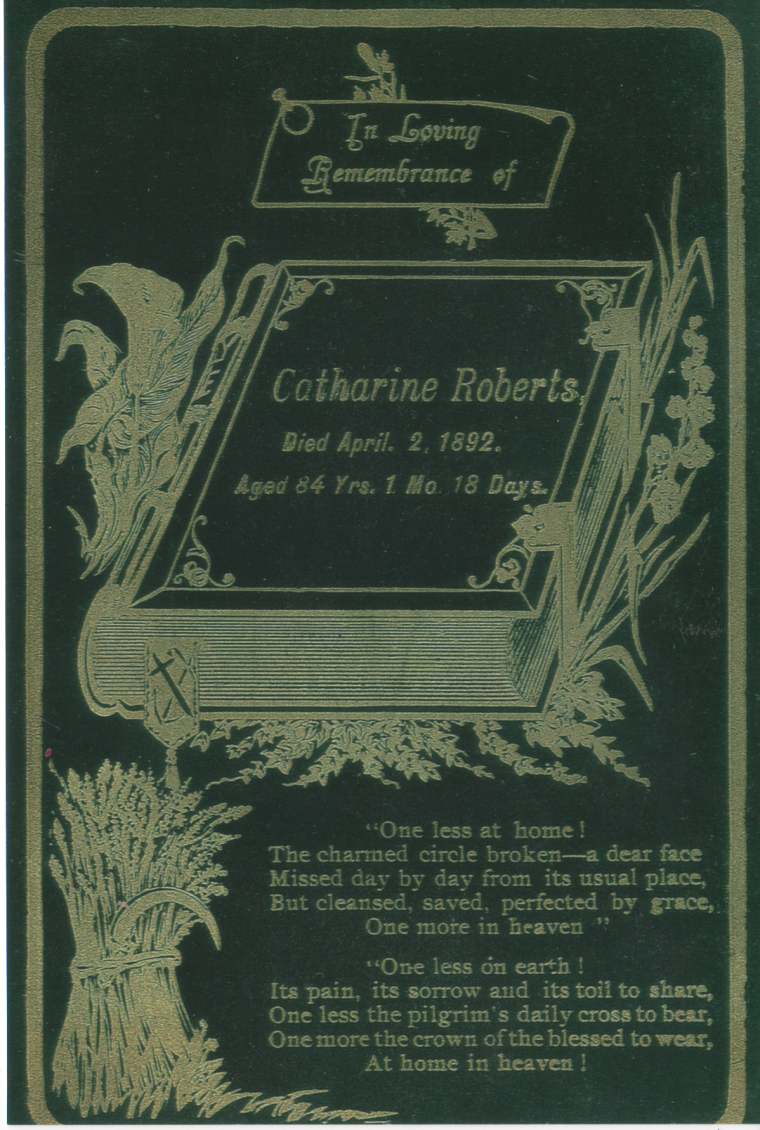

Frank, God bless him, was still a laborer at age 72, while Catherine continued to keep house. The 1890 census cannot be consulted to see what name they were using at that time, since most of the returns were destroyed in a fire. Catherine passed away in 1892 at the age of 84, and her funeral card was preserved in the family (Figure 6).8 At that time she was “Roberts” again.

Figure 6: Funeral prayer card for Catharine (née Schulmerich) Roberts.

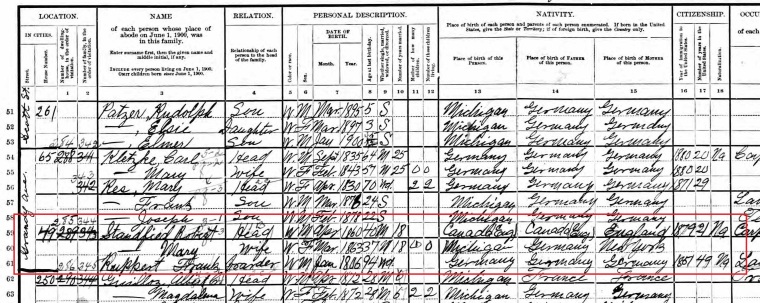

As for her widower husband, Frank, by the 1900 census, enumerated a year before his death, he had come full circle and was listed under the name Fran(t)z Ruppert once again (Figure 7).9 At that time he was living with his daughter, Mary, and her husband, Robert Standfield. This final use of the Ruppert surname doesn’t reflect a lasting change, however, as subsequent generations of the family have continued to use Roberts.

Figure 7: Excerpt from the 1900 U.S. Census for Detroit, Michigan, showing Frantz Ruppert in the Robert Standfield household.

One might ask why the Ruppert family felt compelled to change their surname upon immigration to the U.S.? The answer might lie in the political situation at that time. During the mid 1850s in the U.S., precisely when Franz and Catherine brought their family to America, the American Party, also known as the “Know Nothing movement” was gaining in popularity on the U.S. political scene. This movement arose as reaction against immigrants, mostly Irish and German Catholics, such as Franz and Catherine Ruppert’s family. Know Nothings believed that these immigrants would subvert traditional American values and ultimately make the U.S. subservient to the Pope.10

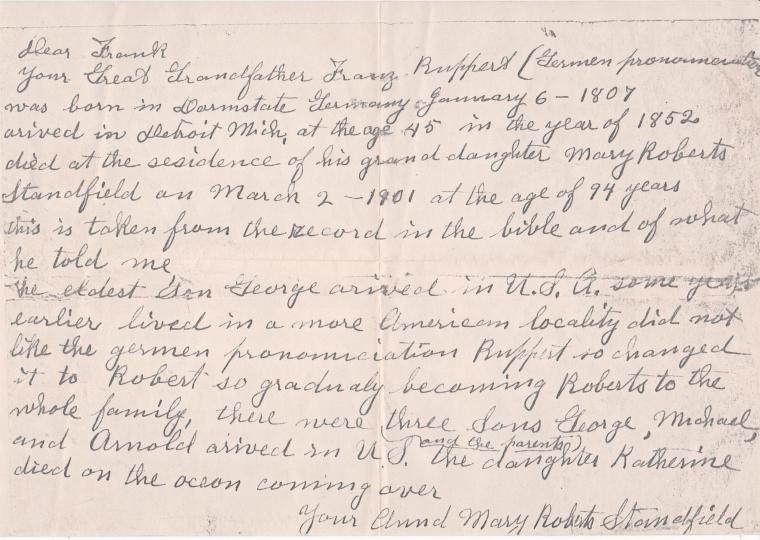

Of course, one could also just ask Aunt Mary Roberts Standfield for her version of the story, recorded in a letter to my great-grandfather (Figure 8).11

Figure 8: Letter from Mary Roberts Standfield to J. Frank Roberts, unknown date.

So there you have it. It was the immigrants themselves, or their descendants, who initiated these name changes. Those poor, maligned Ellis Island officials were almost always blameless. Misspellings may have occurred on passenger manifests, but they were nothing more significant than that. So if you have a story in your family about your name being changed at Ellis Island, dig a little deeper and see what you find.

Sources:

1 Sutton, Philip,”Why Your Family Name Was Not Changed at Ellis Island (and One That Was),” New York Public Library Blogs, 2 July 2013, accessed February 18, 2017.

2 Roman Catholic Church (Heßloch {Kr. Worms}, Hesse, Germany), Kirchenbuch, 1715-1876, marriage record for Franciscus Ruppert and Cath. Elisabetha Schulmerich, 15 January 1830, Family History Library microfilm # 948719.

3 New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 (image), Geo Rupert, S.S. Vancluse, 30 May 1851, http://ancestry.com, subscription database, accessed February 2017.

4 New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 (images), Franz Rupert family, S.S. William Tell, 4 March 1853, http://ancestry.com, subscription database, accessed February 2017.

5 1860 U.S. Census (population schedule), Detroit, Wayne, Michigan, p. 142, Michael Roberts and Frank Roberts households, http://ancestry.com, subscription database, accessed February 2017.

6 1870 U.S. Census (population schedule), Detroit, Wayne, Michigan, p. 126, Michael Robert and Franz Robert households, http://ancestry.com, subscription database, accessed February 2017.

7 1880 U.S. Census (population schedule), Detroit, Wayne, Michigan, E.D. 306, Sheet B, Frank Robert household, http://ancestry.com, subscription database, accessed February 2017.

8 Carol Roberts Fischer funeral home prayer card for Catharine Roberts, 1892; privately held by Carol Roberts Fischer, Hamburg, New York, USA, 2017

9 1900 U.S. Census (population schedule), Detroit, Wayne, Michigan, E.D 126, Sheet 16B, Robert Standfield household, http://ancestry.com, subscription database, accessed February 2017.

10 “Know Nothing,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org, accessed February 2017.

11 Mary Roberts Standfield (Detroit, Michigan, USA) to “Frank” (Mary’s grand-nephew, John Frank Roberts), letter, unknown date; after 1901; privately held by Carol Roberts Fischer, Hamburg, New York, USA, 2017.

© Julie Roberts Szczepankiewicz 2017

Simply fascinating. You tell the story so well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You made some unique points here! Most of my grandparents’ names were not changed at all, but a good example is my Swedish great grandparents. Immigrants seemed to know that “Carlsson” should be changed to Carlson with one S when they came over. I think there was likely a network of information that let most immigrants know that they would be more employable if the name was Americanized and it was totally voluntary.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on "Limesstones".

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Julie,

In response to name changing, my name was changed by the nuns who taught me. It was my first name only and it was changed from Krystyna to Christine. My brother’s name was changed from Roman to Raymond. These were the names used in our records and became official when we were naturalized. I’m not sure how this fits in with your mythology article but the name changes were not our idea. They were imposed on us by our teachers and later became official.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Chris, thank you for your comment. Did you naturalize on your own, or via a parent? If it was via a parent (say, your father), did he write your name on his petition as “Christine” and write your brother’s name as “Roman”? I can easily envision an immigrant being influenced by school officials’ suggestions in this regard. However, I think it would have to be up to the petitioner to write whatever name he or she wished on his petition, so if your father had insisted on Krystyna and Roman, that’s what would have been recorded. But I’m not a lawyer, so this is somewhat speculative. 🙂

LikeLike

My maternal grandfather, in Buffalo, NY went for a job at Bethlehem Steel as Bołeslaw Olejniczak and was turned down. He went back a few weeks later as Bill Olley and was hired.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yep, that’s pretty much how it went! 🙂

LikeLike