In my last post, I wrote about my recent confirmation of the parents of Mary Magdalene (Causin/Cossin) Roberts and the discovery of their place of origin in Pfetterhouse, Haut-Rhin, Alsace, France. Although this was a thrilling breakthrough for me, in hindsight, I’m frankly amazed that it took me this long to find them. Let’s unpack the process and see what can be learned from it.

1. Thorough Documentary Research is Always Key

Although this was definitely a stubborn research problem, it’s probably overstating the case to call it a “brick wall” because the documentary research was far from complete. The Genealogical Proof Standard requires “reasonably exhaustive” documentary research, and it’s up to the researcher to identify all collections that are potentially relevant to the research problem and add them to the research plan. Although I’ve been chipping away at research in onsite collections in Detroit as time and money (and the pandemic….) permit, I had not yet examined all of the relevant birth, marriage and death records from the Roberts’ parish in Detroit, Old St. Mary’s, either in person or by proxy. Similarly, my local Family History Center has not been open for quite a while due to the pandemic, making it difficult to research digitized collections with restricted access, such as the church records from St. Louis in Buffalo, where I might have found death records that offered a transcription of “Cossin” that would have been more recognizable. So, it’s entirely possible that this problem could have been solved solely through documentary research, given enough time and focused effort.

2. Don’t Overlook Online Family Trees

Even if I had accepted immediately that the Maria Magdalena Gosÿ who was baptized at St. Louis church in Buffalo, was my Maria Magdalena Causin, I would have had to rely on FAN research for the identification of their ancestral village, since the baptismal record did not mention the parents’ place of origin. So, finding those family trees that mentioned Anna Maria/Maria Anna Hentzi was a critical clue. One of the things I find most surprising is that searches for “Anna Maria Hensy” did not turn up results for Anna Maria/Maria Anna Hentzy Schneider, given the number of family trees in which she appears. Even now, when I repeat those searches to see if I can tease her out of the database, using only the search parameters I knew previously (before the trees from the DNA matches gave me her married surname), she is not readily found. I like to think I’m not a rookie when it comes to database searches, and I certainly tried a variety of search parameters, based on what I knew for a fact, and as well as what I could speculate.

Assuming that the godmother was actually present at the baptism of Maria Magdalena “Gosÿ,” I knew that “Maria Anna Hensy” was living in Buffalo in 1832, was most likely born in France, and was probably between the ages of 16 and 60 when she served as godmother, suggesting a birth between 1772 and 1816, although I suspected that a narrower range from 1800–1816 was more likely. I guessed that she was also probably living in Detroit by 1857 when Maria Magdalena was married, so I set up parallel searches with either Buffalo or Detroit specified as her place of residence. I tired varying the specificity of the search, leaving out some information, such as approximate year of birth, and I also tried making the search more restrictive by specifying “exact search” for some parameters, such as her place of birth in France. I used wild card characters to try to circumvent problems with variant spellings in the surname, and I performed all these same searches at FamilySearch, since they offer a different assortment of indexed databases. Despite all that, no promising candidates emerged for further research until DNA matches permitted me to focus on particular family trees.

Why might this be? Good question. One thing I did not do was try drilling down to the Public Member Trees database, specifically. It’s standard research practice among experienced researchers to drill down to a particular database where the research target is expected to be found, e.g. “1870 United States Federal Census,” or “New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957,” especially when the desired results don’t turn up readily in broader searches of all the databases, or within a sub-category of databases, like “Immigration & Emigration” or “Census & Voter Lists.” So, although I searched for “Maria Anna Hensy,” in specific historical records databases (e.g. 1840 census, 1850 census, etc.), my research log indicates that I never drilled down to the Public Member Trees to look for clues. I suspect this reflects some unconscious bias on my part—mea culpa! I’m so accustomed to frustration over all the inaccuracies that I find in so many online trees, that I failed to give these trees the consideration they deserved in generating good leads. When I repeat those searches for Maria Anna Hensy in the Public Member Trees database, the correct Maria Anna/Anna Maria Hentzy Schneider shows up in the first page of search results.

3. Analyze the Surname Hints from DNAGedcom

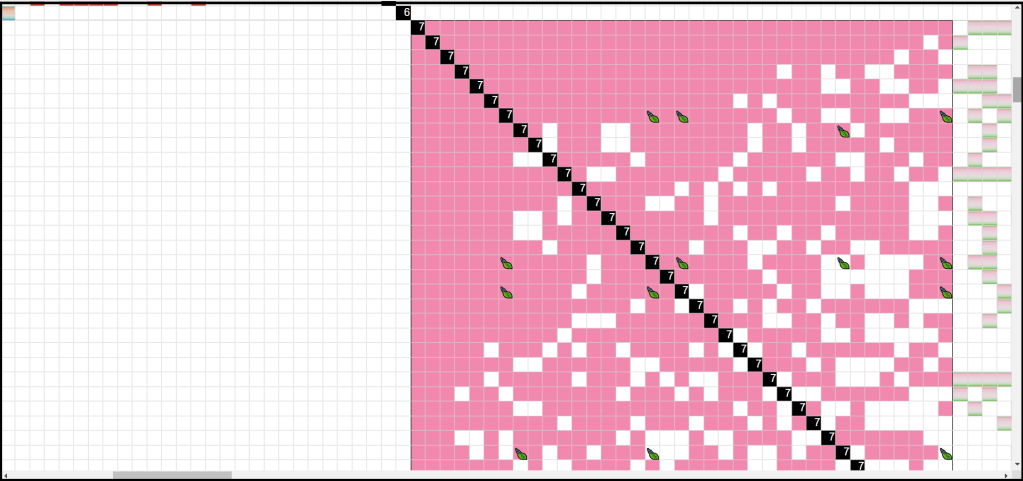

Had I also dug deeper into Aunt Betty’s DNA matches using some of analytical tools out there, I might have found my Cossins sooner. Several weeks ago, I ran a Collins-Leeds analysis at DNAGedcom on all of Aunt Betty’s matches at Ancestry that were within the 20–300 centiMorgan (cM) range, and the results included an enormous cluster with 36 members, whom I realize now are all related through the Hensy line (Figure 1). I’ve written a little previously about DNAGedcom, and more information can be found on their website. However, the purpose of autocluster analysis tools like this is to sort your autosomal DNA match list into clusters of people who are related to each other through a common line of descent.

The really cool thing about DNAGedcom for these analyses is the amount of information that is provided—assuming you take the time to dig into it, which I had not done previously. For that cluster shown in Figure 1, you’ll notice that some of the pink squares are marked with a green leaf. Those leaves mark the intersections of two DNA testers who have family trees linked to their DNA tests, and hovering the cursor over those squares will reveal the names of individuals found in both trees. You can even go one better and tap on any colored square (marked with a leaf or not) to see the option to “View Cluster,” or “View Chromo[some] Browser,” as shown in Figure 2.

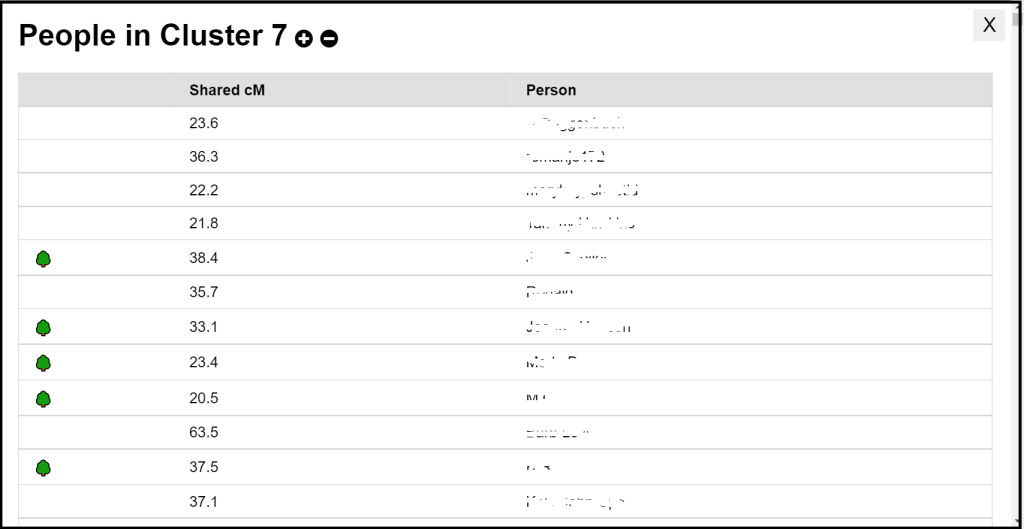

The data used for this autocluster analysis came from Ancestry, and much to the dismay of pretty much everyone interested in genetic genealogy, Ancestry does not offer a chromosome browser or any sort of segment data. So, the “View Chromo Browser” option will not work here, although it would work if these data were gathered from another source like 23&Me. However, clicking on “View Cluster” brings up the chart shown in Figure 3. Names of testers have been redacted for privacy.

Clicking on the name of anyone in that list will take you to the DNA match page for that person at Ancestry. Tree icons on the left indicate those matches with linked family trees. Nice information, but if you keep scrolling down, it gets even better. After identifying the individuals with whom DNA is shared in each cluster, DNAGedcom goes one step further, identifying individual ancestors who appear in the family trees linked to those matches (Figure 4).

The names of the DNA matches who own each family tree are listed in the column on the far right, and have been redacted for privacy, but the chart indicates that Nicolaus, Johann Anton, and Servatius Thelen all appear in 4 different family trees of individual members of Cluster 7, as do Anna Maria and Andrew Schneider and Peter Simon. As it happens, the most recent common ancestral couple between Aunt Betty and these matches—Dionisy Hentzy and Agnes Antony— is not mentioned in this top part of the list. However, if we were to scroll down a bit, we would find them (Figure 5).

Admittedly, this is still a “Some Assembly Required” type of tool. The ancestor list for a given cluster identified by DNAGedcom does not immediately identify the most recent common ancestral couple. However, in conjunction with a list of ancestral FANs, and with guidance from the public member trees, which explain the relationships between individuals mentioned in the list, this is a powerful tool, indeed.

4. Use All the Information in Each Historical Record

The mistake that galls me the most in all of this is that I failed to fully examine the death record for Mary M. Roberts until I sat down to write that first blog post about this discovery. (Actually, had I blogged about my “brick wall” with Maria Magdalena earlier, I might have found my answers faster, since writing about something always forces me to review, organize, and reanalyze my information.) When I looked at my evidence for her date of death, I noticed that I had her probate packet and cemetery records, but I was still citing the index entry for her Michigan death certificate, which I had obtained years ago, and not the original record, which is now readily available online. Duh! One of the cardinal rules of genealogy is to always go to the original source, rather than trusting the information in an index, because so often there is additional information in the original, or there are transcription errors that are caught after viewing the original. Such was the case here, as well. The index entry, shown in Figure 6, only states that Mary M. Roberts was born “abt. 1833.”1

However, the entry from the death register contains more information than was indexed regarding her precise age at the time of death.2 The death register states that she was 61 years, 6 months, and 10 days old when she died, as shown in Figure 7.

When I ran this through a date calculator (such as this one), it points to a birth date of 17 August 1832. This is almost an exact match to the birth date of 14 August 1832 that was noted on the baptismal record for Maria Magdalena “Gosÿ” from St. Louis Church in Buffalo.

Facepalm.

Had I made this connection sooner, I would have been much more confident in accepting that baptismal record as the correct one for Mary Magdalene Causin/Casin/Curzon/Couzens. I guess this is why we have Genealogy Do-Overs. All of us start our research by making rookie errors, so at the very least, it’s important to periodically step back and re-evaluate the search to see what is really known, and to make sure that nothing has been overlooked. Better still, consider a full-blown, Thomas MacEntee-style Do Over, which I have never yet had the courage to do.

Not all breakthroughs are the result of elegant or sophisticated methodology. Sometimes, you just keep hacking away at a problem, and you get to the answer in the end, and that’s what happened here. While the origins of the Causin family could possibly have been discovered, in time, using thorough documentary research in church records from Detroit and Buffalo, the process was expedited when the focus switched from the Causin surname to the Hentzy surname of one of their FANs. With the addition of insight gained from examination of DNA matches, the process was expedited still further. The combination of cluster research, autosomal DNA matching, and standard documentary research, is so powerful that it can even overcome a flawed research process. So, while this may not have been a pretty victory, it was a victory nonetheless. I’ll take it.

© Julie Roberts Szczepankiewicz 2021

Sources:

1 “Michigan, U.S., Deaths and Burials Index, 1869-1995,” database, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/ : 17 November 2021), Mary M. Roberts, died 27 February 1894, citing Family History Library film no. 1377697.

2 “Michigan Deaths and Burials, 1800-1995,” database and image, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FHH5-3XW : 17 November 2021), Mary M. Roberts, 27 February 1894, citing Wayne, Michigan, Deaths, v. 13-17 1893-1897, no. 3598.

Nice! I do enjoy reading your offerings, though I have not caught on to the DNA possibilities. Do-overs are revealing and sometimes embarrassing! I’ve got files 30 years old to fix and pass on. Well, my daughter-in-law has a program that changes pdfs to “pages”, so all is not lost. When I began I never included photos or doc. images in my essays … so much to do and so little time! (I’m under hospice care.) So we’ll see. It has been quite a trip! So much fun and so rewarding. Thanks as always,Sarah

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sally! How wonderful to hear from you! I was thinking of you the other day and wondering how your Konin research project is coming along. I’m so happy I was able to be a part of it. Hospice….wow. Losing my mom last year has really taught me how fleeting is our time here, and I’ve been “sweating the small stuff” much less as a result. My thoughts and prayers are with you as you continue on your journey. I never had the privilege of meeting you in person in this life, but I hope that we will greet each other as old friends, with joy, in the next. May God bless you, draw you close to Him, and bring you comfort and peace.

LikeLike

Julie,

What a wonderful article. Love how you took apart each step and explained how it worked. So many people do not check everything and original records are the key. Checking back on work you have done is such a great way to check and confirm your information.

Keep up the good work. Enjoy your newsletters.

Barbara Murphy

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the kind words, Barbara! Best wishes for success in your research!

LikeLike

Julie,

I always enjoy reading your blog. It teaches me and makes me reexamine things in a good way.

Thanks,

Paul Baltzer

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Paul. You’re very kind.

LikeLike

Julie

I truly enjoy all your articles. I have high hopes that some of my ancestry mysteries can be resolved..as you are pointing me in the right direction!

Thanks

Debbi

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your kind words, Debbi, and best wishes for success with your ancestor hunt. I so enjoy sharing the journey with like-minded genealogy folks through this blog!

LikeLike

I admit I don’t know much about the DNA part of Ancestry.com, but I appreciate how you didn’t give up until you found Magdalena. I too have hesitated to trust Public Member Trees because of exactly what you said: the number of glaring inaccuracies that are out there. But I have also found some good information there, including photos of ancestors I’m researching that were posted on trees relating to their in-laws, ex-spouses or even friends. I have a couple of “mystery people” in my tree, but I’m not giving up. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I don’t plan to make that same mistake again by not giving those online trees due consideration! I have a few other “brick walls” that I hope to apply this strategy to as well. Good luck with your mystery people!

LikeLiked by 1 person

😊

LikeLiked by 1 person