Christiana (_____) Hodgkinson (c. 1788–1865) was my fourth great-grandmother, married to Robert Hodgkinson of Grantham Township on Canada’s Niagara Peninsula.

For decades, her maiden name and parentage have eluded me—and many other Hodgkinson researchers.

When I first discovered my descent from Robert and Christiana after posting on an old RootsWeb message board for Lincoln County, Ontario, back in 2006, another seasoned researcher cautioned me:

“People have been looking for Christiana’s maiden name for over 20 years. So far, no luck. There was speculation that she may have been a Corson as one of her daughters was named Catherine ‘Cor.,’ but all of that is pure speculation. No proof whatsoever.”¹

As I dug deeper, I found another popular theory suggesting Christiana might have been a Larraway. The Larraway family was certainly connected to the Hodgkinsons through the marriage of Robert and Christiana’s daughter, Eleanor Jane, to James Larraway in 1839.² Given the endogamy among settlers in Upper Canada, it wouldn’t have been surprising to find additional ties between the two families.

A distant cousin even mentioned a family Bible record in which Christiana’s maiden name was penciled in as Larraway, then crossed out, as if the writer weren’t certain.³ The theory was appealing: there were plenty of Loyalist Larraways in the Niagara Peninsula, including one Jonas Larraway, himself a Loyalist like Robert Hodgkinson’s father. And in 1829, Robert Hodgkinson placed a newspaper ad for a lost English watch inscribed with the initials “J.L.”⁴ Could that watch have belonged to his father-in-law, Jonas Larraway?

It was just the kind of tantalizing clue that keeps a genealogist awake at night. But despite its appeal, I was never able to find convincing evidence for this theory in the historical record. So, what was the truth of Christiana’s origins?

Christiana in the Records

Because of record loss, Christiana appears in only one census—the 1861 enumeration—which listed her as age 61 and born in Upper Canada.⁵ However, her daughter Elizabeth (Hodgkinson) Walsh stated in the 1900 U.S. census that her mother was born in New York.⁶

Christiana’s death notice, published in the St. Catharines Constitutional on 14 September 1865, reported that she was 77 years old at death, suggesting a birth circa 1788.⁷ Her grave marker at Victoria Lawn Cemetery records her death on 5 September 1864, “Aged 76 Yrs. & 8 M.,” implying a birth in December 1788 or January 1789.⁸ No surviving church records identify her parents or birthplace.

A Breakthrough with Full-Text Search

That was where my research stood—until recently, when I was playing with FamilySearch’s Full-Text Search feature. This AI-driven tool, introduced at RootsTech 2024, has revolutionized genealogical discovery by revealing text buried deep within unindexed images. I’d used it before to glean small clues, but this time, it changed everything.

A simple search for “Christiana Hodgkinson” in Canada, 1790–1866, surfaced a Revolutionary War pension file.⁹

My jaw hit the floor. This was the breakthrough I’d been looking for.

Christiana Hodgkinson was née Griffiths, or Griffis.

Somehow, amid the Loyalist settlement of Grantham, there was a family—my family!—who applied to the U.S. government for a pension they believed was owed to their patriarch for his Revolutionary War service.

The Pension File That Changed Everything

The 48-page file was pure genealogical gold. It revealed that Christiana was the daughter of James and Catherine (Froelich) Griffiths or Griffis and that she had at least six siblings, including Sarah Griffis, who married Francis Hodgkinson—the brother of Christiana’s husband, Robert.¹⁰

Suddenly, the puzzle pieces snapped together: two Hodgkinson brothers had married two Griffis sisters.

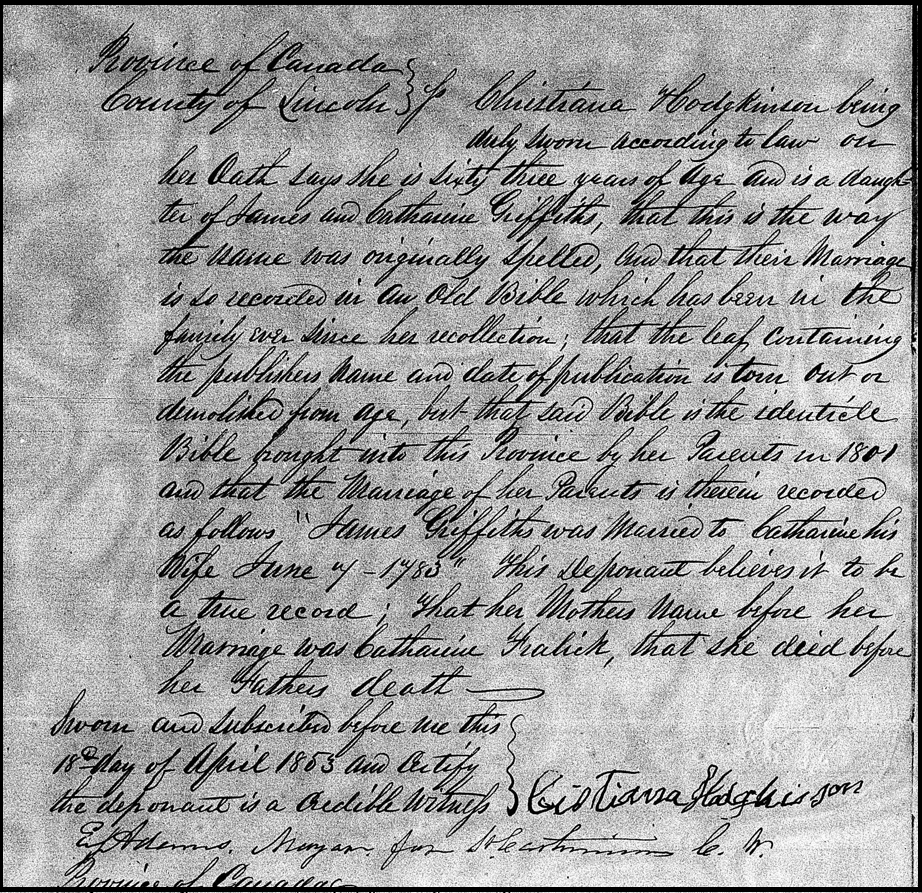

James Griffiths was the son of Peter from “Albanii” (Albany), and Catherine was the daughter of Barend Froelich. They were married 13 June 1783 at Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church in Athens, Greene County, New York. It was stated that that “the family originally came from Wales and spelt their name Griffiths until after the Revolution, it was written Griffis, as it was shorter and more like the pronunciation.”

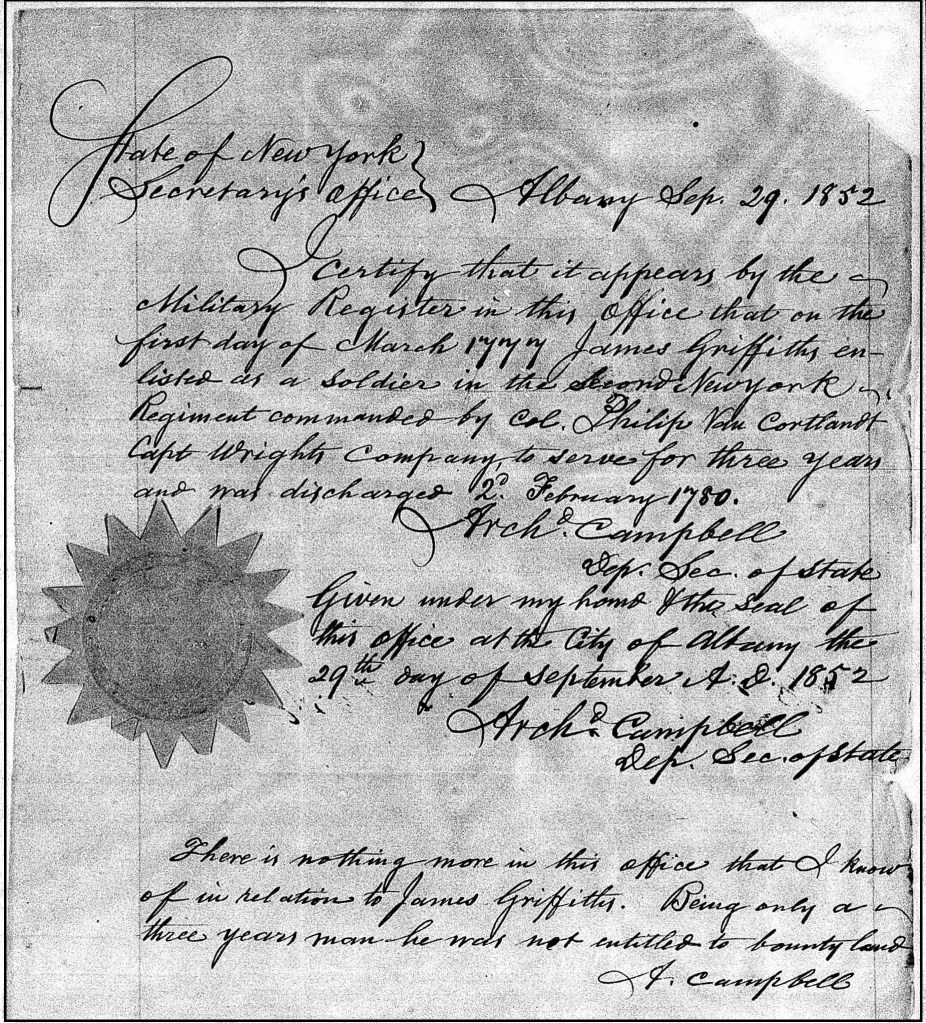

James Griffiths fought on the American side—unlike most of my ancestors of that era, who were Loyalists. A certificate dated 1852 from Archibald Campbell, Deputy Secretary of State in Albany, confirmed that James enlisted 1 March 1777 in Capt. Jacob Wright’s company, Second New York Regiment, commanded by Col. Philip Van Cortlandt. He served three years and was discharged 2 February 1780.

James and Catherine Griffiths migrated to Canada around 1800, settling in Grantham, where Catherine died 17 November 1835 and James died 18 December 1837. They were buried together in the Episcopal Burying Ground at Ten Mile Creek.

A Bureaucratic Saga

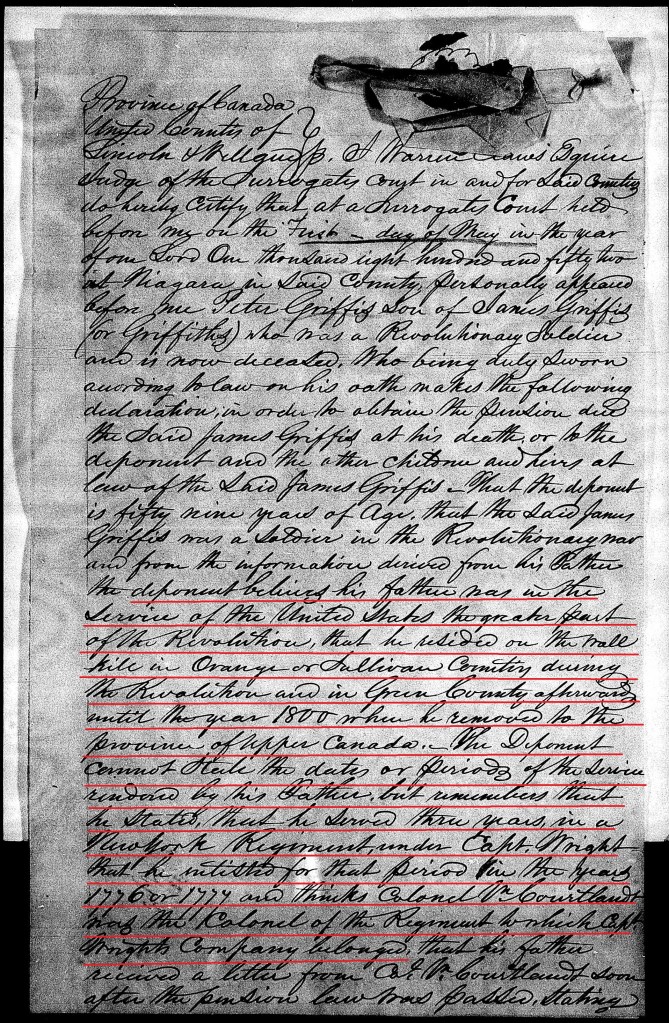

All this information appeared within affidavits filed in 1852 by their son Peter Griffis, who believed he and his siblings were entitled to their father’s pension as a Revolutionary War veteran. Among those documents was his sworn declaration describing his father’s service (Figure 1), and identifying his father’s heirs as himself, Mary Larraway, Sarah Hodgkinson, Christiana Hodgkinson, Lydia Courson, and Hannah Oustroudt.

Despite the certificate from the Deputy Secretary of State dated 29 September 1852 (Figure 2), the Pension Office equivocated, writing in March 1853 that the claim might be approved if James Griffiths’s identity could be firmly established:

“If his name was formerly Griffith, it can be proved by the production of the Family Record, or a certified Copy.… If the claim is a meritorious one, it is very remarkable that application has been deferred until this late day.”

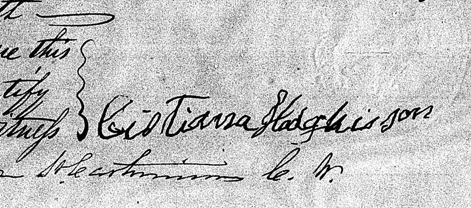

Christiana Hodgkinson herself replied in an affidavit—signed in her own hand—attesting to her name, age, parents, and the date of her parents’ marriage, which was recorded in their family Bible brought to Canada around 1800 (Figure 3). Lawrence Corson also testified that he had examined that Bible and believed it to be an original record of James and Catherine’s marriage.

From 1853 to 1859, the family persisted. Their attorney defended the claim, explaining the name change from Griffith to Griffis and the delay caused by their Canadian residence. The pastor of Zion Lutheran Church sent a certified copy of the 1783 marriage record. In September 1859, Sarah Hodgkinson wrote again, still believing children could inherit pensions, and demanded payment for seven years of service at the rate of $8 per month with 6% interest over 77 years, which she calculated to amount to $3,776.46. Her angry letter went so far as to threaten legal action if denied.

You have to love her chutzpah.

Ultimately, the claim was rejected. Some confusion might have been avoided if the Pension Office had clearly stated back in 1852 that Revolutionary War pensions extended only to veterans and widows—not to their heirs. However, they didn’t state that until 1859, in their response to Sarah Hodgkinson. Meanwhile their earlier replies, suggesting that there was insufficient evidence linking James Griffiths the soldier with James Griffis of Grantham, seem puzzling. What are the odds that Peter Griffis could accurately describe the enlistment details of an unrelated James Griffiths?

Connecting the Dots

With the identification of James and Catherine (Froelich) Griffiths as Christiana’s parents, and Lydia (Coursin/Corson) as her sister, two loose ends finally made sense.

The death certificate for James George Welch (Walsh), son of Robert and Elizabeth (Hodgkinson) Walsh, incorrectly reported his mother’s maiden name as Griffith instead of Hodgkinson¹¹ The informant, his wife Jane (Lawder) Walsh, obviously confused her mother-in-law’s maiden name with that of Elizabeth’s mother.

Another clue appears in St. Mark’s Anglican Church Baptisms, Niagara-on-the-Lake, 1792–1856: on 3 January 1816, Barnabas Corson, son of Lawrence and Lydia, was baptized with sponsors Jno. (John) Hodgkinson and Jas. (James) and Catherine Griffiths.¹² It’s clear now that Barnabas’s mother, Lydia (Griffiths) Corson, chose her own parents, and her brother-in-law’s father, as godparents for her son.

Conclusions

The Pension Office’s handling of this case reveals both bureaucratic confusion and subtle bias. Their skepticism may have stemmed from the fact that the claim originated within a known Loyalist settlement in Upper Canada. Indeed, there exists a land petition from a Peter Griffis citing Loyalist service during the Revolution.¹³ That petitioner stated he came to Canada circa 1800, coinciding with Christiana’s family’s arrival. But the Peter Griffis who was Christiana’s brother was born about 1793—too young to have served—so the Loyalist claimant was likely a paternal uncle.

The Griffis family thus embodied the divided loyalties of that era: relatives on both sides of the Revolutionary War. James Griffis was certified to have served honorably on the American side, even if later bureaucrats buried that certification as the final page beneath forty-seven pages of correspondence in his file.

It’s also striking that the old theories weren’t entirely wrong. Christiana’s sisters really did marry into the Corson and Larraway families that researchers long suspected.

Looking back 173 years later, I’m oddly grateful that the Pension Office never clarified in 1852 that a pension claim died with the veteran and his widow. Had they done so, my fourth great-grandmother might never have submitted her affidavit—and her signature, a tangible link to her life, might never have been preserved.

Notes

- Name withheld for privacy, author’s research files.

- Library and Archives Canada, List of Marriage Licences Issued in Upper Canada (RG 5 B9), LAROWAY, James, and HODGKISON, Eliza [sic] Jane, 24 July 1839.

- Name withheld for privacy, author’s research files.

- The Farmers’ Journal and Welland Canal Intelligencer (St. Catharines, Ontario), 8 Apr 1829, p. 3, “Watch Lost.”

- 1861 Census of Canada, Canada West, Lincoln District 22, Grantham Sub-District 6, p. 4, Robert Hodgkinson household; LAC RG31, Microfilm C-1048–1049.

- 1900 U.S. Census, Erie Co., N.Y., Buffalo Ward 24, ED 212, Sheet 3A, Charles DeVere household; NARA T623, roll 1032.

- St. Catharines Constitutional (14 Sept 1865), p. 3, death notice for Christina Hodgkinson.

- Victoria Lawn Cemetery (St. Catharines, Ontario), monument inscription for Christiana Hodgkinson.

- U.S. Dept. of Veterans Affairs, Revolutionary War Pension File R4321, James Griffis or Griffiths; NARA M804, Roll 1133; digital image, FamilySearch.

- Find a Grave memorial #99489809 for Sarah Hidgkinson (1787–1865), North Embro Cemetery, Oxford Co., Ont.; Niagara Peninsula Branch OGS, St. Mark’s Anglican Church Baptisms, Niagara-on-the-Lake, 1792–1856, p. 22.

- Ontario Death Certificate 1924 no. 032688, George James Welch, 18 June 1924; FamilySearch database, “Canada, Ontario Deaths, 1869–1937.”

- St. Mark’s Anglican Church Baptisms, Niagara-on-the-Lake, 1792–1856, p. 23, entry for 3 Jan 1816, Barnabas Corson.

- Upper Canada Land Petitions 1819, Vol. 206, Bundle G12, no. 44, Peter Griffis of Louth; LAC RG1 L3, Microfilm C-2030.

© Julie Roberts Szczepankiewicz, 2025