We all have things we wish for, hope for, and dream about. As genealogists, sometimes our dreams might be considered a little unusual, like longing for an extant copy of the 1890 U.S. census for each enumeration district where one had relatives living at that time. But as the old saying goes, “If wishes were horses, beggars would ride.” In some cases, all the wishing in the world will be in vain, because the thing we want may no longer exist—like the 1890 census. Sometimes it’s possible to obtain the same information in some other way—for example, using a state census or city directory to document an ancestor’s residence in a certain location circa 1890. At other times, we just have to resign ourselves to the reality that what we want is truly unavailable, and the information will be difficult or impossible to obtain by any other means.

When it comes to my Polish ancestors, I’ve always dreamed about prenuptial agreements. Anyone who’s ever read a civil marriage record from Russian Poland is familiar with that standard wording in Polish or Russian (depending on the time period) that translates, “The newlyweds stated that they had made no prenuptial agreement,” or words to that effect. This phrase is contained within the legalese that comes at the end of the record, and this legalese is often ignored because it rarely contains any information of genealogical significance. I’ve personally translated at least a couple hundred marriage records from Russian Poland at this point, and I can think of only a few cases where a couple signed a prenuptial agreement. In each case, the prenuptial agreement was noted in a marriage record I translated for someone else’s research, never for my own ancestors. Records from marriages which were preceded by the signing of a prenuptial agreement include a statement that the couple signed the agreement with notary X in such-and-such town on such-and-such date, and sometimes a document number is provided.

Nowadays, we might think of prenups as agreements drawn up to protect each party’s assets in the event of a divorce. However, this was rarely a consideration for Polish peasants in the 19th century, since divorces were not recognized in the Catholic Church. Nonetheless, since the era of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, both men and women had the right to manage the assets which they brought into a marriage in the form of a posag (dowry) or wiano (groom’s equivalent of a dowry), and both parties had legal rights in the event of a breach of the marital contract.1 While one might expect that only the noble class would be motivated to draw up such agreements, there were nevertheless instances in which peasants created premarital agreements as well. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, sometimes premarital contracts were created in order to define the manner in which the parents of the bride or groom would be cared for in their old age by their children. A few interesting examples of such premarital agreements can be found in the Russian translation forum for premarital agreements at Genealodzy.pl. In one example of a prenup from 1908, the engaged couple appeared before the notary with the bride’s widowed mother. After establishing that each party’s assets would be held jointly throughout the marriage, the contract went on to describe a farm owned by the bride’s mother, which she intended to give to the newlyweds, with the stipulation that she be allowed to continue to live there until her death, and with compensation being made to each of the bride’s siblings to ensure that they received a share in the inheritance. The contract specified the accommodations that the bride’s mother was to be given—one room with a southern exposure, a loft above it, and other entrances—along with provisions, such as defined quantities of peat, grain, and potatoes, enough land to keep four hens, a pig, and a vegetable garden as well as pasture for her cow.2 In this particular agreement, I found it charming that even the name of the cow was specified. Who wouldn’t love to know this kind of information?

Such prenuptial contracts offer a fascinating glimpse into the lives of the individuals described therein, which is why I’ve always hoped to discover one pertaining to my own family. Unfortunately, they’re relatively rare, as mentioned, and I’ve never found any evidence for a prenuptial agreement drawn up by my ancestors—until recently. Several months ago, the marriage record for my great-great-grandparents, Stanisław Zieliński and Marianna Kalota, came into my hands (Figure 1).

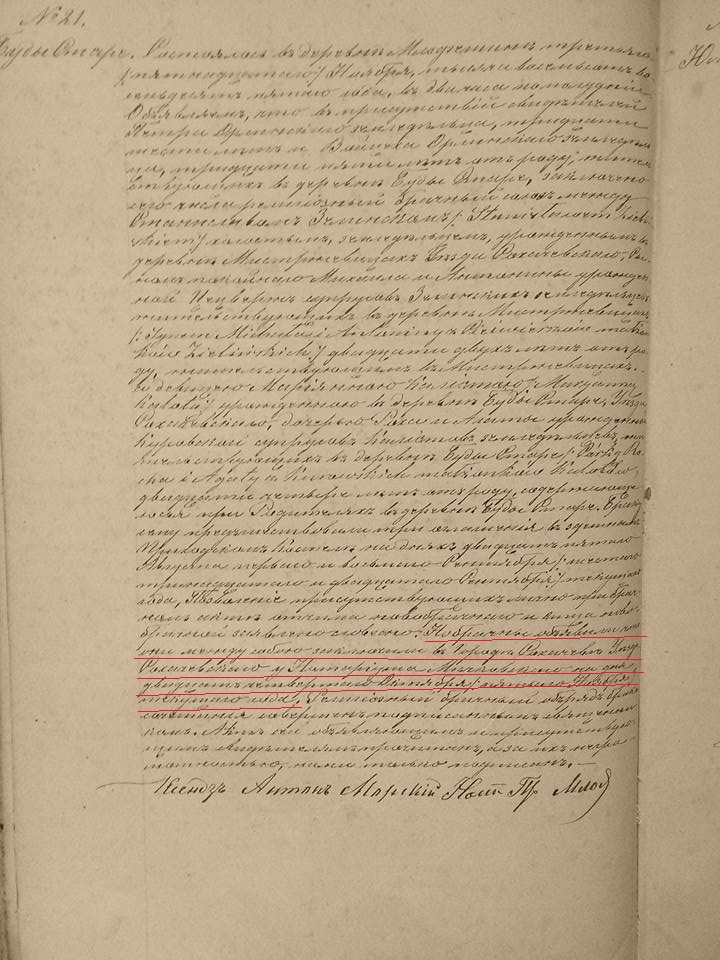

Figure 1: Marriage record from Młodzieszyn parish for Stanisław Zieliński and Marianna Kalota, 15 November 1885, with text regarding prenuptial agreement underlined in red.3

In translation from Russian, the record reads as follows:

“No. 21, Budy Stare. This happened in the village of Młodzieszyn on the 3rd/15th day of November 1885 at 2:00 in the afternoon. We declare that, in the presence of witnesses—Piotr Orliński, farmer, age 36, and Wojciech Orliński, farmer, age 35, residents of the village of Budy Stare—on this day was contracted a religious marriage between Stanisław Zieliński, bachelor, farmer, born in the village of Mistrzewice, Sochaczew district, son of the late Michał and still-living Antonina née Ciećwierz, the spouses Zieliński, farmers residing in the village of Mistrzewice; age 22, residing in Mistrzewice, and Miss Marianna Kalota, born in the village of Budy Stare, Sochaczew district, daughter of Roch and Agata née Kurowska, the spouses Kalota, farmers residing in the village of Budy Stare; age 24, living with her parents in the village of Budy Stare. The marriage was preceded by three announcements in the local parish church on the 25th of August [and the] 1st, and 8th days of September/6th, 13th, and 20th days of September of the current year. Permission for the marriage was given orally by the stepfather of the groom and the father of the bride who personally attended the wedding. The newlyweds stated that they made a prenuptial agreement in the town of Sochaczew, district of Sochaczew with Notary Mieczkowski on the 24th day of October/5th day of November of the current year. The religious ceremony of marriage was performed by the undersigned clergyman. This document was read aloud to the declarants and witnesses present, and because of their illiteracy, was signed only by us.”

“The newlyweds stated that they had made a prenuptial agreement…”? What!? As soon as I read that, I pulled up Szukajwarchiwach on my computer to see if they had records from this notary Mieczkowski in their collection. If you’re unfamiliar with this site, it’s the search portal that catalogs the holdings of most of the state archives in Poland. Although Stanisław and Marianna’s marriage record did not provide the notary’s given name or a document number, the marriage contract should be fairly easy to locate nonetheless just by knowing the town and date on which it was signed, assuming that the archive has the relevant collection.

To my utter disappointment, there were no results from a notary named Mieczkowski in Sochaczew in 1885. There was, however, a collection of records from a notary named Andrzej Mieczkowski that began in 1886—but he was from the town of Mińsk Mazowiecki, some 70 miles east of Sochaczew. Could there possibly be two notaries with the same surname working in different locations in the same time period in Poland? Or was it the same notary, who moved from Sochaczew to Mińsk Mazowiecki in 1886? Geneteka offers some evidence (albeit weak) that the latter theory may be correct. There is a birth record in Sochaczew in 1878 for Jadwiga Teresa Mieczkowska, daughter of Andrzej Mieczkowski and Walentyna Sawicka, and a death record in 1877 for Władysław Wacław Mieczkowski, son of the same couple. These dates would be consistent with a residence in Sochaczew during the late 1870s-early 1880s followed by a relocation to Mińsk Mazowieckie in 1886. There are no vital records from Mińsk Mazowieckie found in Geneteka for any Mieczkowskis, and there are no scans of these records online that could be checked to see if the baby’s father was noted to be a notary. Of course, research into the life of the notary himself is somewhat tangential to the question of where his records might be found, but disappointment and desperation can drive one to grasp at all sorts of straws.

Adding fuel to the fire, I discovered that Marianna’s sister, Barbara Kalota, also signed a prenup with a notary named Mieczkowski, and this time, his given name was recorded as Andrzej. Her marriage record (Figure 2) is translated below.

Figure 2: Marriage record for Barbara Kalota and Józef Mikołajewski, 20 November 1881, with text regarding prenuptial agreement underlined in red.4

“This happened in the village of Młodzieszyn on the 8th/20th day of November 1881 at 2:00 in the afternoon. We declare that—in the presence of witnesses, Andrzej Wilczek, farmer, age 52, and Jan Winnicki, farmer, age 42, residing in the village of Budy Stare—on this day was contracted a religious marriage between Józef Mikołajewski, bachelor, land-owning farmer, born in the village of Młodzieszyn, Sochaczew district, son of Karol and Tekla née Grabowska, the spouses Mikołajewski, land-owning farmers residing in the village of Juliopol; age 26, residing in the village of Juliopol, and the maiden Barbara Kalota, born in the village of Budy Stare, Sochaczew district, daughter of Roch and Agata née Kurowska, the spouses Kalota, farmers residing in the village of Budy Stare, age 22, living with her parents in the village of Budy Stare. The marriage was preceded by three announcements in the local parish church on days 25th October, 1st and 8th November/6th, 13th, and 20th November of the current year. Permission for the marriage was given by those present at this marriage Act, the mother of the groom and the father of the bride who were present at the wedding. The newlyweds stated that they contracted a prenuptial agreement between them in the town of Sochaczew, Sochaczew district, with notary Andrzej Mieczkowski on the 23rd day of October/4th day of November of the current year.The religious rite of marriage was performed by the undersigned priest. This document was read aloud to the declarants and witnesses present, and due to their illiteracy, it was signed only by Us. Fr. Antoni Morski.”

So at this point, we know that Barbara and Marianna, who were the two oldest daughters (discovered to date) of Roch and Agata Kalota, both had prenuptial agreements. Death records inform us that Agata died in 1895 and Roch died in 1921, so it is possible that one or both of these prenuptial agreements was intended to specify the care that Roch and Agata were to receive from their children in their old age.5 But why would two such agreements be necessary? Or was it coincidence that both prenups involved the Kalota sisters? Perhaps one of the agreements stipulated care for the aging parents of the groom, Józef Mikołajewski or Stanisław Zieliński, rather than the parents of the bride?

Obviously, the marriage contracts themselves will provide the answers we need, so the burning question remains: do these marriage contracts still exist, and if so, where? We’ve already established that notarial records from 1881-1885 for Andrzej Mieczkowski in Sochaczew are not mentioned in Szukajwarchiwacz, but that does not necessarily mean that these records were destroyed. Szukajwarchiwach is known to be incomplete, although no one seems to be able to estimate how incomplete it is. It’s possible that these records do exist in an archive in Poland, and perhaps are known to the archivists, but have yet to be catalogued. The regional archive that covers Sochaczew is the Grodzisk Mazowiecki branch of the state archive of Warsaw. I wrote to them recently to inquire about the possibility that they have these notarial records in their collection, and I’m keeping my fingers crossed for a favorable reply. If they do not have the records, then perhaps the branch archive in Otwock, which covers Mińsk Mazowieckie, has them. There’s a slight chance they might be someplace like the civil registry office (urząd stanu cywilnego, or USC) in Sochaczew or Mińsk Mazowiecki. However, it’s also possible that the records did not survive the wars, so the information contained therein is truly lost.

Often, the hard part is knowing when the time has come to accept defeat, because all realistic options for finding the records of interest have been exhausted. Time and again, I have been surprised by how many Polish archival records did survive the wars, and time and again, I have encouraged others not to buy into the myth that there’s no point in pursuing Polish genealogical research because “all the records were destroyed in the wars.” Sometimes, success lies merely in a combination of perseverance and knowing where to look. Time will tell if I am ever able to track down the premarital agreements for Marianna and Barbara Kalota, and if I’m ultimately successful, you may hear me shouting about it from the rooftops. In the meantime, hope dies last.

© Julie Roberts Szczepankiewicz 2018

Sources:

Special thanks to Monika Deimann-Clemens for editing my Russian translations of the marriage records.

Featured Image: Wodzinowski, Wincenty. Wesele. Digital image. Muzeum Ludowych Instrumentów Muzycznych W Szydłowcu, http://muzeuminstrumentow.pl/ : 8 September 2015. Web. 8 October 2018.

1 Siuta, Dawid. “Staropolskie małżeństwo – umowy przedślubne narzeczonych i ich rodzin,” Historykon, 21 April 2016, https://backend.historykon.pl, accessed 7 October 2018.

2 Danecka, “Umowa przedmałżeńska z 1908,” Tłumaczenia – rosyjski – Umowa przedślubna, discussion forum, 30 December 2009, https://genealodzy.pl/PNphpBB2-printview-t-9669-start-0.phtml : accessed 7 October 2018.

3 Roman Catholic Church, Młodzieszyn parish (Młodzieszyn, Sochaczew, Mazowieckie, Poland), “Akta stanu cywilnego parafii rzymskokatolickiej w Młodzieszynie,” 1885, marriages, #21, record for Stanisław Zieliński and Marianna Kalota, 15 November 1885.

4 Roman Catholic Church, Młodzieszyn parish (Młodzieszyn, Sochaczew, Mazowieckie, Poland), “Akta stanu cywilnego parafii rzymskokatolickiej w Młodzieszynie,” 1881, marriages, unknown record number, marriage record of Józef Mikołajewski and Barbara Kalota, 20 November 1881.

5 “Akta stanu cywilnego parafii rzymskokatolickiej w Mlodzieszynie,” Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne, Metryki.genealodzy.pl: Projekt Indeksacji Metryk Parafialnych (http://metryki.genealodzy.pl : 7 October 2018), Jednostka 301, Księga zgonów 1889-1901, 1895, no. 69, death record for Agata Kalota; and

“Akta stanu cywilnego parafii rzymskokatolickiej w Mlodzieszynie,” Księga zgonów 1914-1925, 1921, no. 58, death record for Roch Kalota, Urząd stanu cywilnego gminy Młodzieszyn (Młodzieszyn, Sochaczew, Mazowieckie, Poland).

A census was taken in 1890 in New York City and still survives at the Municipal Archives in NYC. Known as the 1890 Police Census, it is an extremely important resource and particularly interesting because, unlike a regular census, the policeman clearly knew the family. In my case, a daughter named Wislawa is listed as “Wishie”, so we learn the name the family actually called her. Not indexed; use a NYC directory to get a street address. Read the description and very partial listing on ancestry.com and/or see Family History Library microfilm numbers #1304781, #1309970, and #1304777.

LikeLike

Rather than the 1890 Police Census (which is useless to me since I have no ancestors from New York City) I prefer to use the 1892 New York State census, in combination with city directories, to document my ancestors circa 1890. That said, I’m not primarily interested in the 1890 census, since there are so many work-arounds, as I mentioned in the article. It was primarily intended to be an example of something that genealogists often wish for that no longer exists.

LikeLike

An index for the 1890 Police Census is available at familysearch.com in New York research page with 1,479,855 names. No image is available (yet). Important to see the original image; the indexer misread the names in my Polish family.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The New York City portion of the 1892 NY Census is lost; ditto the Bronx. That’s why 1890 Police Census is o important for those of us with families living in NYC. Aside from that, of course you are correct about missing records that are either gone forever–or hopefully have yet to be discovered.

LikeLiked by 1 person