Newcomers to Polish genealogy often start with a few misconceptions. Many Americans have only a dim understanding of the border changes that occurred in Europe over the centuries, and in fairness, keeping up with all of them can be quite a challenge, as evidenced by this timelapse video that illustrates Europe’s geopolitical map changes since 1000 AD. So it’s no wonder that I often hear statements like, “Grandma’s family was Polish, but they lived someplace near the Russian border.” Statements like this presuppose that Grandma’s family lived in “Poland” near the border between “Poland” and Russia. However, what many people don’t realize is that Poland didn’t exist as an independent nation from 1795-1918.

How did this happen and what were the consequences for our Polish ancestors? At the risk of vastly oversimplifying the story, I’d like to present a few highlights of Polish history that beginning Polish researchers should be aware of as they start to trace their family’s origins in “the Old Country.”

Typically, the oldest genealogical records that we find for our Polish ancestors date back to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which existed from 1569-1795. At the height of its power, the Commonwealth looked like this (in red), superimposed over the current map (Figure 1):1

Figure 1: Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth at its maximum extent, in 1619.1

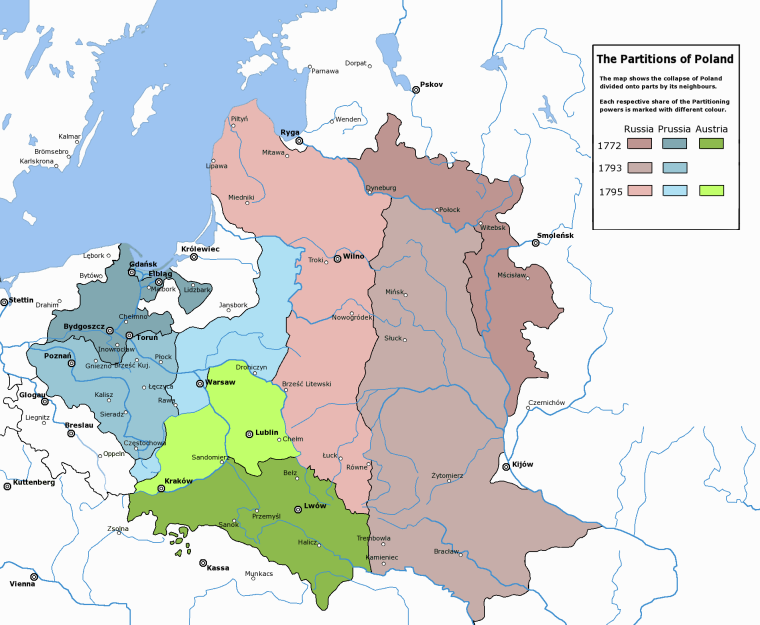

The beginning of the end for the Commonwealth came in 1772, with the first of three partitions which carved up Polish lands among the Russian, Prussian, and Austrian Empires. The second partition, in which only the Russian and Prussian Empires participated, occurred in 1793. After the third partition in 1795, among all three empires, Poland vanished from the map (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Map of the Partitions of Poland, courtesy of Wikimedia.2

This map gets trotted out a lot in Polish history and genealogy discussions because we often explain to people about those partitions, but I don’t especially like it because it sometimes creates the misconception that this was how things still looked by the late 1800s/early 1900s when most of our Polish immigrant ancestors came over. In reality, time marched on, and the map kept changing. By 1807, just twelve years after that final partition of Poland, the short-lived Duchy of Warsaw (Figure 3) was created by Napoleon as a French client state. At this time, Napoleon also introduced a paragraph-style format of civil vital registration, so civil records from this part of “Poland” are easily distinguishable from church records.

Figure 3: Map of the Duchy of Warsaw (Księstwo Warszawskie), 1807-1809. 3

During its brief history, the Duchy of Warsaw managed to expand its borders to the south and east a bit thanks to territories taken from the Austrian Empire, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Map of the Duchy of Warsaw, 1809-1815.4

However, by 1815, following the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the Duchy of Warsaw was divided up again at the Congress of Vienna, which created the Grand Duchy of Posen (Wielkie Księstwo Poznańskie), Congress Poland (Królestwo Polskie), and the Free City of Kraków. These changes are summarized in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Territorial Changes in Poland, 1815 5

The Grand Duchy of Posen was a Prussian client state whose capital was the city of Poznań (Posen, in German). This Grand Duchy was eventually replaced by the Prussian Province of Posen in 1848. Congress Poland was officially known as the Kingdom of Poland but is often called “Congress Poland” in reference to its creation at the Congress of Vienna, and as a means to distinguish it from other Kingdoms of Poland which existed at various times in history. Although it was a client state of Russia from the start, Congress Poland was granted some limited autonomy (e.g. records were kept in Polish) until the November Uprising of 1831, after which Russia retaliated with curtailment of Polish rights and freedoms. The unsuccessful January Uprising of 1863 resulted in a further tightening of Russia’s grip on Poland, erasing any semblance of autonomy which the Kingdom of Poland had enjoyed. The territory was wholly absorbed into the Russian Empire, and this is why family historians researching their roots in this area will see a change from Polish-language vital records to Russian-language records starting about 1868. The Free, Independent, and Strictly Neutral City of Kraków with its Territory (Wolne, Niepodległe i Ściśle Neutralne Miasto Kraków z Okręgiem), was jointly controlled by all three of its neighbors (Prussia, Russia, and Austria), until it was annexed by the Austrian Empire following the failed Kraków Uprising in 1846.

By the second half of the 19th century, things had settled down a bit. The geopolitical map of “Poland” didn’t change during the time from the 1880s through the early 1900s, when most of our ancestors emigrated, until the end of World War I when Poland was reborn as a new, independent Polish state. The featured map at the top (shown again in Figure 6) is one of my favorites, because it clearly defines the borders of Galicia and the various Prussian and Russian provinces commonly mentioned in documents pertaining to our ancestors.

Figure 6: Central and Eastern Europe in 1900, courtesy of easteurotopo.org, used with permission.6

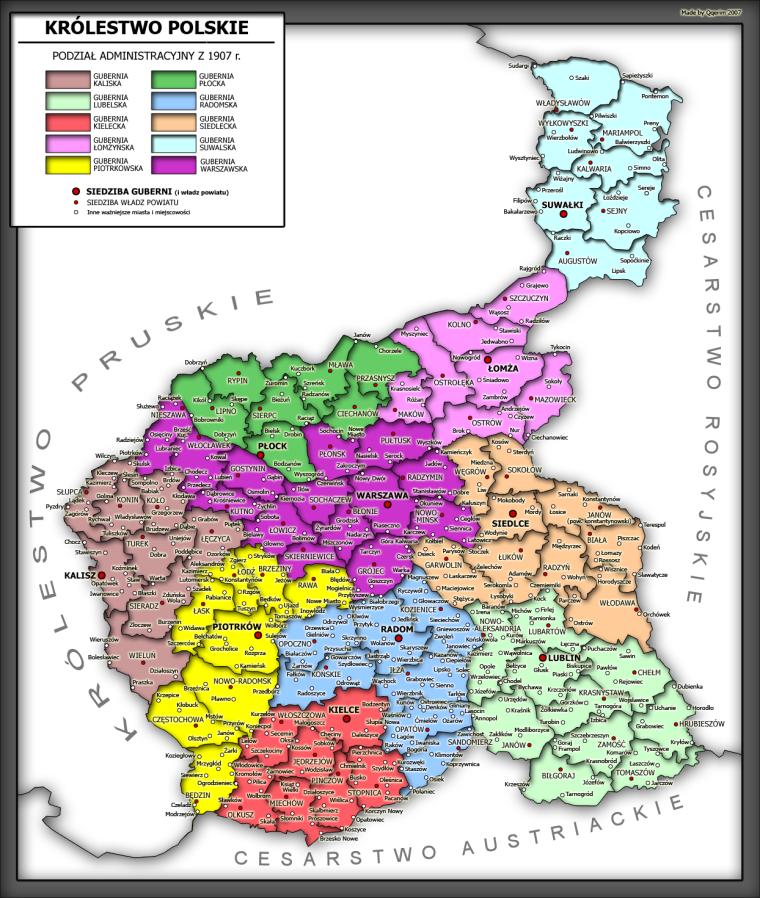

Although the individual provinces within the former Congress Poland are not named due to lack of space, a nice map of those is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Administrative map of Congress Poland, 1907.7 (Note that some sources still refer to the these territories as “Congress Poland” even after 1867, but this name does not reflect the existence of any independent government apart from Russia.)

The Republic of Poland that was created at the end of World War I, commonly known as the Second Polish Republic, is shown in Figure 8. The borders are shifted to the east relative to present-day Poland, including parts of what is now Lithuania, Ukraine, and Belarus. This territory that was part of Poland between the World Wars, but is excluded from today’s Poland, is known as the Kresy.

Figure 8: Map of the Second Polish Republic showing borders from 1921-1939.8

During the dark days of World War II, Poland was occupied by both Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. About 6 million Polish citizens died during this occupation, mostly civilians, including about 3 million Polish Jews.9 After the war, the three major allied powers (the U.S., Great Britain, and the Soviet Union) redrew the borders of Europe yet again and created a Poland that excluded the Kresy, but included the territories of East Prussia, West Prussia, Silesia, and most of Pomerania.10, 11 At the same time, the Western leaders betrayed Poland and Eastern Europe by effectively handing these countries over to Stalin and permitting the creation of the Communist Eastern Bloc.12

To conclude, let’s take a look at how these border changes affected the village of Kowalewo-Opactwo in present-day Słupca County, Wielkopolskie province, where my great-grandmother was born. This village was originally in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, but then became part of Prussia after the second partition in 1793. In 1807 it fell solidly within the borders of the Duchy of Warsaw, but by 1815 it lay right on the westernmost edge of the Kalisz province of Russian-controlled Congress Poland. After 1867, the vital records are in Russian, reflecting the tighter grip that Russia exerted on Poland at that time, until 1918 when Kowalewo-Opactwo became part of the Second Polish Republic. Do these border changes imply that our ancestors weren’t Poles, but were really German or Russian? Hardly. Ethnicity and nationality aren’t necessarily the same thing. Time and time again, ethnic Poles attempted to overthrow their Prussian, Russian or Austrian occupiers, and those uprisings speak volumes about our ancestors’ resentment of those national governments and their longing for a free Poland. As my Polish grandma once told me, “If a cat has kittens in a china cabinet, you don’t call them teacups.”

Sources:

1“Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth at its maximum extent” by Samotny Wędrowiec, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, accessed 9 January 2017.

2 “Rzeczpospolita Rozbiory 3,” by Halibutt, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, accessed 9 January 2017.

3 “Map of the Duchy of Warsaw, 1807-1809,” by Mathiasrex, based on layers of kgberger, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0., accessed 9 January 2017.

4“Map of the Duchy of Warsaw, 1809-1815” by Mathiasrex, based on layers of kgberger, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, accessed 9 January 2017.

5 “Territorial Changes of Poland, 1815,” by Esemono, is in the public domain, accessed 9 January 2017.

6 “Central and Eastern Europe in 1900,” Topgraphic Maps of Eastern Europe: An Atlas of the Shtetl, used with permission, accessed 9 January 2017.

7 “Administrative Map of Kingdom of Poland from 1907,” by Qquerim, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, accessed 9 January 2017.

8 “RzeczpospolitaII,” is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, accessed 9 January 2017.

9 “Occupation of Poland (1939-1945),” Wikipedia, accessed 9 Janary 2017.

10 “Potsdam Conference,” Wikipedia, accessed 9 January 2017.

11 “Territorial changes of Poland immediately after World War II,” Wikipedia, accessed 9 January 2017.

12 “Western betrayal,” Wikipedia, accessed 9 January 2017.

© Julie Roberts Szczepankiewicz 2017

If my great grandfather came to America around 1912-1914 and his records date he was came from “austria-Poland” could you tell me what that means? We grew up often hearing that our family lived in what was now known as ukraine.

LikeLike

Hi Beth, as noted in that article, Poland did not exist as an independent nation from 1795 until 1918. So for the period from 1912–1914, your great-grandfather was living in the Austrian Empire, in a part of Austria-Hungary that is now Ukraine. Depending on the record, if it says “Austria – Polish” that might suggest that he was an ethnic Pole (probably Roman Catholic and speaking Polish as his native language).

LikeLike

Thank you so much for the reply…that’s what I thought I was getting from your article but I wanted to be sure I understood correctly. It’s very confusing how we all have these stories of where our families come from but records don’t really give us any specifics. Thank you again for the clarification!

LikeLike

Your final paragraph was very helpful as your Polish grandmother grew up about 4 miles from my grandfather’s village of Dolany p Ladek near Ciazen. It’s nice to have such a succinct review of the geopolitical changes in that specific area.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Linda, what was the name of your grandfather from the village of Dolany? Have you researched his ancestry in records from Lądek? There’s a nice index for that area at http://www.slupcagenealogy.com/SearchPg.aspx, if you’re not already familiar with it. I’d be very interested in learning more about your research and the other surnames in your family tree from that area. Have you done DNA testing?

LikeLike

Need to clarify one thing. Jozef Stobinski was born in Dziedzice at his grandparents’s farm and shortly after his parents moved to Ladek where his siblings were all born. I always forget to mention that part.

I found the Slupca Genealogy site last year and it has been very helpful.

I have found records for Stobinki/Stoginski, Rewers, Wasielewski, and Szymanski which gets me back to my grandfather’s grandparents so far (early 1800s).

I have done dna testing for my paternal side, but maternal dna testing is on my wish list, along with purchasing Hoffman’s books.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the clarification. I have Rewers in my family tree, but only by marriage. Marcianna Rewers daughter of Franciszek and Katarzyna, married Andrzej Franciszek Dąbrowski in Kowalewo in 1857. Andrzej was the brother of my great-great-great-grandmother, Jadwiga Anna Dąbrowska. Autosomal DNA testing provides information on all branches of the family (maternal and paternal), so it’s the most useful type of DNA testing for genealogists. Y-DNA (male line) and mitochondrial DNA (maternal line) also have their place and can help answer specific questions, but they’re not as generally useful as autosomal testing. Best wishes!

LikeLike

thank you for your informative article. My maternal grandparents were from Futoma Austria which is the listed

place of their birth. They came to the US in 1912. My mothers maiden name was MNICH. There is a mountain

with that name. I believe Futoma was West of Krakow close to Russia. Is there a website to help me research the

family tree MNICH. First names were Marcel (M) and Tekla (F) I would love any info you might provide me

Thank you so much

LikeLike

Hi Barbara! Many of the records from Futoma are online at Szukajwarchiwach:

Birth records from 1784–1824, 1832: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/en/jednostka/-/jednostka/18245251

Birth records from 1824–1881: https://tinyurl.com/Births-1824-through-1881

Marriage records from 1784–1850: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/en/jednostka/-/jednostka/18245253

Marriage records from 1851–1899: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/en/jednostka/-/jednostka/19881814

Death records from 1784–1852: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/en/jednostka/-/jednostka/18245254

Death records from 1852–1898: https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/en/jednostka/-/jednostka/19881813

There’s also this collection at FamilySearch with digitized records from Futoma from 1784–1865: https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/334867?availability=Family%20History%20Library Access is restricted to computers at your local LDS Family History Center or Affiliate Library. I haven’t compared that to what’s already online at Szukajwarchiwach, so I can’t confirm the existence of unique collections at FS that aren’t at SwA, but you can check that for yourself.

If you need additional records beyond these (i.e. more recent than 1899, or older than 1784, Lucjan Cichocki is a researcher based in Przemyśl who can probably assist you with onsite research. He’s helped me with a great deal of research in parishes and archives in this area. You can contact him through his website, here: https://www.polishancestryresearch.com/

Hope this helps. Good luck! 🙂

LikeLike

Very interesting information! My maternal grandmother was Polish. Her father was born in 1876 in what was then part of Germany (according to his naturalization papers) and emigrated to the US via Bremen in 1896. I’ve been trying to figure out where exactly he was born, but either I’m misreading the name of his birthplace on the papers, it’s misspelled, or the town no longer exists. It looks like “Gnowselioef” but could also be “Gnowscliof.” His surname was Plewaski / Plewacka / Plewacki (the spelling varies on different documents).

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s likely to be a mistranscription of a German name for a place that’s currently located in Poland and known by a Polish name, but I hesitate to take a guess without seeing the source document. You might consider uploading images of your documentation to one of the Polish genealogy groups for assistance in deciphering the place name. There are various gazetteers such as Kartenmeister and the Meyers Gazetteer that are helpful in identifying places in the Prussian partition; links can be found under “Gazetteers” in the Genealogy Toolbox menu at the top of the page.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have family that would list Russia Poland as where they were born but would also just list Russia but later census Germany. Surname Koch and place mentioned spelled Kunin or Konin also Kamin .

LikeLike

My family had the same issue of identity between Russian Poland and German Poland. They were from Ladek in the Konin area.

My immigrant grandfather thought he was from the Russian area in 1893, but clearly he was from the Congress Poland area on the border with Germany (Ladek) which later became Prussian Territory. Sometimes its better to ask relatives if they were oppressed by the Kaiser or the Czar. The Konin area was very much a mix of Germans and Poles. I suspect

immigrants may have been confused by English terms Prussian and Russian

LikeLike

I, too, am researching ancestors from Konin and Słupca counties, which were in the Kalisz gubernia, near the Russia-Prussia border. Based on my personal research experience, I don’t believe that our ancestors were confused by the terminology (Russia vs. Prussia), nor do I believe they were confused about their own identity as Russian or Prussian citizens. Rather, I would look carefully at the documents which reported the discrepancies. If there were only a few discrepancies, and they were found in census records, I would suspect that the census-taker recorded the information in error, since census records are particularly prone to such inaccuracies. If there are multiple documents created by different entities, and the research subjects have common names, I would be very careful to verify that the records with the discrepancies actually pertain to your ancestors and not to other immigrants with the same names.

LikeLike

Thank you, I’m glad to hear they were not confused. However, I certainly was. Finding the border between Prussia and Russia was only clear on your website. Ladek and Slupca were right on the border and it was only 1867 that these residents became subject to the Russian military draft, I believe. It caused my 17 year old grandfather to emigrate to the US in 1893.

Ancestors talked about Russian sectors and German sectors of Poland but it was primarily through your website that I could discern where those areas were and when. Thank you for being clear and direct on that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My father told me my great grandmother and great Aunt spoke Russian, German , Polish and Yiddish they were both seamstresses. So that area must have been very fluid in who was in control.

LikeLike

It was a multicultural, multiethnic area, certainly, but from the perspective of our immigrant ancestors, Konin was under Russian control—and only Russian control—dating back to the creation of the Congress Kingdom of Poland (Królestwo Polskie) in 1815. See Figures 5 and 6 in the preceding article.

LikeLike

Yes thank you I did read the article which was very informative, my great grandfather was born in 1879 and on his naturalization paper he listed Russian as birthplace , but I’m pretty sure he was born in Konin.

LikeLike

I’m having trouble identifying which Landsberg in Poland is the correct location of my husband’s family. Immigration records from Norddeutscher Lloyd, sailing from Bremen to NYC in 1900, state: Landsberg, Nativity: Country: Russia, Province: Warsaw, Mother Tongue: German, Subject of What Country: Russia. Are they from Gorzów Wielko (Landsberg an der Warthe), Gorzów Ślaski (Landsberg in Upper Silesia), or Górowo Iławeckie (Landsberg, Preußiche Eylau, East Preußen)? Any thoughts would be helpful. Your website has been very helpful in understanding the changing landscape of the Polish borders. Thank you. Rebecca

LikeLike

Hi, Rebecca! That is a tricky question. Landsberg definitely sounds like a German place name, but the Warsaw gubernia was in the Russian Empire. So, although I didn’t really expect to find it there, I checked the Skorowidz Królestwa Polskeigo (a gazetteer of the Kingdom of Poland, which included the Warsaw gubernia) nonetheless, and it does not indicate any places by this name. I suspect that a recording error was introduced on the manifest someplace, and I would advise trying to locate additional evidence for place of origin, perhaps from naturalization records, passenger manifests from other members of the family’s FAN club, cemetery records, etc. If I had to guess based solely on this piece of evidence, I’d go with Górowo Iławeckie (Landsberg, Preußiche Eylau, East Preußen) based on its proximity to Russia.

LikeLike

Thank you so very much for your input. There are other towns in this family’s records but they are impossible to read, but always Landsberg is mentioned. Census records indicate that they are Russian, then later German but always German as the native tongue. I will be traveling to Poland hopefully this Fall to visit other family sites and wanted to make sure I was visiting the correct Landsberg. Many thanks for your interesting and informative website!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very informative! New to Polish research, after 25 years I just tracked down ny Henry Goldberg in London 1891 via his passenger list reference Henroch Goldberg via Hamburg in 1895 from his home town of Strzyzow, a major breakthrough for me

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for clarifying a complex topic with clarity – well done!

For ancestry, is there any guide or database for phonetic spellings or commonly misspelled towns? In my research, got the town written in ship records but can’t seem to find the town. Very simple for area – Galicia, Krakow, Kingdom of Austria from naturalization papers. LOL! And I can’t find any records by name. Looked at database of Galician towns but not 100%.

LikeLike

Thanks for the kind words, Vernon! I’d be happy to take a look if you want to send me a link to the passenger manifest, but there IS, in fact, an excellent phonetic gazetteer for this purpose: the JewishGen Gazetteer: https://www.jewishgen.org/communities/loctown.asp

This, and other online gazetteers, are indexed in the Genealogy Toolbox on my website: https://fromshepherdsandshoemakers.com/gazetteers-for-polish-genealogy/.

LikeLike

Awesome! I will take a look.

The link I have is from the Statue of Liberty – Ellis Island Foundation, Line 22:

https://heritage.statueofliberty.org/passenger-details/czoxMjoiMTAxOTg0MDQwMjYyIjs=/czo4OiJtYW5pZmVzdCI7

Theresia Borkowska although it is typed as “Burkowska, Theresia -1907 – Trszingel, Austria

Came with 3 kids (Otto Karl, Alfred) under Borkowska name but they later took father’s name when adults and he is listed as their father in the US records – Marion Roessler. Really trying to find him and his location but nothing thus far. Otto was my grandfather.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry for the slow reply, Vernon, I’m just getting to this now….

Ooof! That IS a tough one, and it’s a little too far south for my comfort zone. I’m pretty good at finding place in Poland, but the manifest states that these folks were Moravian. As for the place name, Ancestry has it transcribed as Trigriych, Hungary, and it looks to me like Trazinych, for whatever that’s worth. I suggest you take all three of those spellings and try plugging them into the JewishGen Gazetteer, searching according to Daitch-Mokotoff Soundex rather than the default, Beider-Morse Phonetic Matching. That’ll give you more search hits to play with. Then sift through your list of matches, pulling out the ones that were located within the historical borders of Moravia. You can use this map as a guide: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f7/Map_of_Moravia.jpg

You may also want to consider joining a Facebook group, such as this one for Moravian Genealogy: https://www.facebook.com/groups/Moravian.Genealogy

Usually, there are locals in those groups who are familiar with the place names. Experienced eyes — and ears that recognize how Moravian place names might have been spelled phonetically by immigration officials — might be able to tell you right away what that place name is supposed to be. Sorry I can’t be of more assistance. Good luck!

LikeLike

Thank you SO much for the information! This is a big help and a direction I

needed. Can’t thanks enough!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awesome information in here! I have been trying to triangulate Rozyszcze, apparently part of Ukraine but reportedly at one time Poland (Volyn Oblast), in order to provide an accurate timeline for when these ancestors move from one town to another.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, Margaret! I’m not sure I understand your use of the term “triangulate” in this context, but the Skorowidz miejscowości Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, which is a gazetteer of places that were in the Second Polish Republic (between the wars), identifies Rożyszcze as located in gmina Rożyszcze, Łuck powiat, and Wołyń województwo (p. 1461). The city is currently known as Рожище (Rozhyshche) in the Volyn Oblast in Ukraine. Wikipedia has some history and links, if you haven’t seen these already. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ro%C5%BCyszcze (Btw, the Polish versions of Wikipedia articles are usually more informative than the English ones for locations like this.) Links to this gazetteer, and many others are on my Maps and Gazetteers page: https://fromshepherdsandshoemakers.com/gazetteers-for-polish-genealogy/ . Let me know if you have further questions.

LikeLike

This article is very helpful! I am researching a family named Zujewski for a friend and my head is spinning. I could use a birthplace opinion. John Zujewski (1863-1921) told a U.S. county clerk (for a marriage license) that he was born in “Mensk, Russia” (as written by the clerk). However, on three U.S. census documents, he reports he and his parents were from “Russia (Pol)”, 1900 census; “Russia (Pol)”, 1910 census; and “Poland” no mention of Russia (1920 census). He obviously identified strongly as Polish (he came to US in 1893 and settled in a Polish community in Omaha by 1898). I came across a “Jan Zujewski” on a passenger list in 1893 who said he was Russian and last residence Lomza, but gave his age as 32 (born 1861). Since both Minsk, Belarus and Minsk in Poland were within the Russian Empire when he was born, I don’t know which to zero in on. The surname Zujewski-Zyjewski-Zajewski can be found on Geneteka in Poland and Belarus, but I can’t find a John/Jan linked to parents (Pawel and “Aggie” or Leokadia) in Minsk, Belarus or Minsk, Poland. It doesn’t help that his birth year could be 1863-64-65 or even 1869, depending on how he answered a question about his age. Any opinion, or is this one of those mysteries of genealogy? Thank you!

LikeLike

Hi, Kathy! I’m glad you found the article helpful. I think you’re on the right track with equating “Mensk” with “Mińsk.” A search in the Skorowidz Królestwa Polskiego (a gazetteer of places in the Kingdom of Poland, i.e. “Russian Poland,” published in 1877) does not mention any places called Mensk, and the closest phonetic match is Mińsk (Mazowiecki). There was probably no mention of Russia on the 1920 census because Poland became an independent nation again in 1918, which suggests that John’s birthplace would have been within Polish borders in 1920. That excludes Mińsk in Belarus, which was part of Russia in 1920. I’m also inclined to think that the earlier references to “Russia (Pol)” suggest the Congress Kingdom of Poland, which was controlled by Russia. All of that points to Mińsk Mazowiecki as the location mentioned on the marriage record. Between that, his approximate birth year (1861-1865), and parents’ names from the marriage record (Paweł Zujewski and “Aggie”/Leokadia “Kilsinski,” we should have enough information to start seeking records from Poland. However, as you’ve discovered, the situation is not so simple. Birth records from Miński Mazowiecki are indexed for the period from 1805-1884 with no gaps, and there is no birth record for Jan Zajewski/Zyjewski/Żujewski in Mińsk, or in any indexed parish within 15 km. So, either Mińsk is the wrong place, or he was approximating his place of birth to some small village in Mińsk County which has not yet been indexed.

When I hit a snag like this, I try to find additional evidence for place of origin. The passenger record which you found for Jan Zujewski in 1893 seems like a plausible match, but Jan’s last residence, Łomża, is 100 miles from Mińsk Mazowiecki. (By the way, 1861–1865 is not an unreasonable age span to find reported on U.S. records for Polish immigrants, so I wouldn’t be too put off by the fact that the passenger manifest suggests a birth year circa 1861.) Our ancestors were more mobile than we often assume, and the Łomża-Mińsk discrepancy may reflect that. Łomża was also the name of a gubernia of Congress Poland that was created in 1867, but that doesn’t help us here, because Mińsk Mazowiecki seems to have always been located in the Warsaw gubernia as far as I can tell, never in Łomża.

Besides passenger manifests, church records (if created in a Polish church) often provide evidence for place of origin. The marriage license you found on Ancestry indicates that they were married in Howard County, NE in 1902, and a quick internet search reveals that multiple ethnic Polish parishes existed in Howard County at that time (see https://polishfamily.info/grand-island-diocese). I would contact the diocese and see where those records are now, and try to find the church marriage record for John and Antonina.

Naturalization records are another good source for specific place of origin, especially if created after 1907. John reported in 1900 and 1910 that he was naturalized, but in 1920, his naturalization status was reported as “papers submitted.” This discrepancy suggests that there was a miscommunication somewhere along the way, but it would be worth finding John’s naturalization records, just in case they provide a birthplace more specific than just “Russia.”

It’s also helpful to work the FAN club (Friends, Associates, Neighbors) to gather more evidence for place of origin. In this case, that passenger manifest provides a useful clue because it reveals that John’s destination was Middletown, CT. That suggests that he had family there, or at least some close friends. A quick search on Ancestry produced a declaration of intention to naturalize for Mateusz Zyjewski from New Britain. At this point, it’s impossible to say how or if he’s related to John Zujewski, but New Britain is only 12 miles from Middletown, and Mateusz reported a DOB of 14 September 1863, which would make him John’s contemporary. His place of birth was recorded as “Hambin, Russia” which is, I suspect, a mistranscription of Gąbin. (You can hear how Gąbin is pronounced in Polish here: https://translate.google.com/?sl=pl&tl=de&text=G%C4%85bin&op=translate). Maddeningly, this doesn’t help us much, either. Records from Gąbin are indexed in Geneteka for the time period around Mateusz’s birth, and he’s not there. It might be worth it to look for additional Zujewski/Zyjewski/Zajewskis in the New Britain/Middletown area to see where they were reported to be from.

Finally, we could approach this from the perspective of the surname itself. Zujewski/Żujewski and variants (Zajewski/Żajewski/Zyjewski) are relatively rare surnames, so we should (theoretically) be able to leverage surname distribution maps to help in our search. The Słownik Nazwisk (http://herby.com.pl/) reveals that, circa 1998, there were only 146 people living in Poland with the Żujewski surname, with 48 of them living in Ciechanów County (1998 borders). Żyjewski (265 bearers) was more prominent in Ostrołęka County (55 bearers), which bordered Ciechanów County to the east. There were 81 people with the surname Zajewski, with a preponderance in Warsaw County, and 21 people with the Żajewski surname, all in Warsaw County. John’s mother’s maiden name, “Kilsinski,” does not exist anywhere in that form in indexed historical records in Geneteka; it may have been Kolsiński, Kulsiński, Kulszyński, etc., or even something like Kołaciński, making it difficult to do any kind of geographical analysis. That would be another reason to try to locate the church record of John’s marriage: it’ll give you additional evidence for his mother’s maiden name, hopefully recorded by a priest who had some knowledge of Polish phonetics. Of course, as luck would have it, there are zero examples anywhere in Geneteka of these two surnames existing in the same parish.

The bottom line is that it’s premature to conclude that John’s parents will forever be unknown to posterity. However, you’ll have to go beyond online research in order to make progress. Get those naturalization records and church marriage record I mentioned. Research the heck out of any known relatives John had in the U.S., including his wife, Antonina (nee Marcińska/Marczyńska). Look into Z*jewskis in Connecticut, and consider DNA testing to identify the origins in Poland of DNA matches on the Zujewski line. Leave no stone unturned. Good luck!

LikeLike