Newcomers to Polish genealogy often start with a few misconceptions. Many Americans have only a dim understanding of the border changes that occurred in Europe over the centuries, and in fairness, keeping up with all of them can be quite a challenge, as evidenced by this timelapse video that illustrates Europe’s geopolitical map changes since 1000 AD. So it’s no wonder that I often hear statements like, “Grandma’s family was Polish, but they lived someplace near the Russian border.” Statements like this presuppose that Grandma’s family lived in “Poland” near the border between “Poland” and Russia. However, what many people don’t realize is that Poland didn’t exist as an independent nation from 1795-1918.

How did this happen and what were the consequences for our Polish ancestors? At the risk of vastly oversimplifying the story, I’d like to present a few highlights of Polish history that beginning Polish researchers should be aware of as they start to trace their family’s origins in “the Old Country.”

Typically, the oldest genealogical records that we find for our Polish ancestors date back to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which existed from 1569-1795. At the height of its power, the Commonwealth looked like this (in red), superimposed over the current map (Figure 1):1

Figure 1: Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth at its maximum extent, in 1619.1

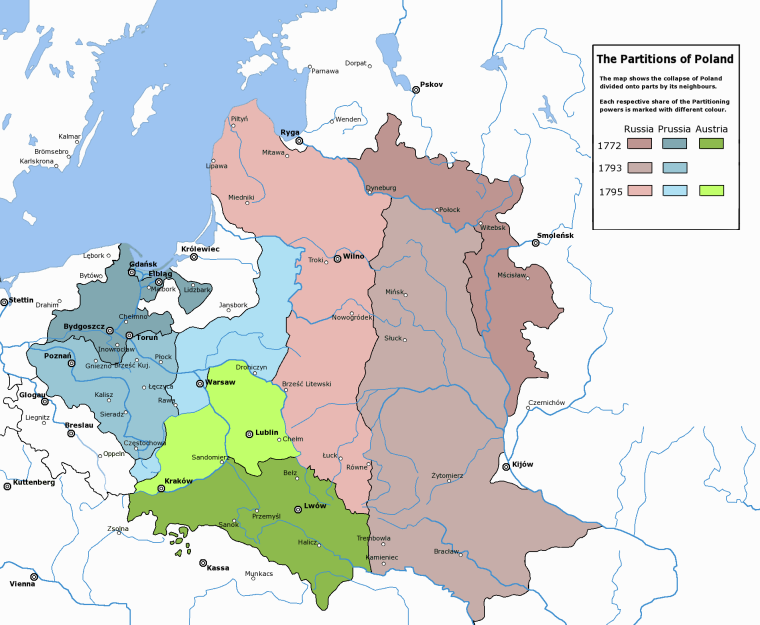

The beginning of the end for the Commonwealth came in 1772, with the first of three partitions which carved up Polish lands among the Russian, Prussian, and Austrian Empires. The second partition, in which only the Russian and Prussian Empires participated, occurred in 1793. After the third partition in 1795, among all three empires, Poland vanished from the map (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Map of the Partitions of Poland, courtesy of Wikimedia.2

This map gets trotted out a lot in Polish history and genealogy discussions because we often explain to people about those partitions, but I don’t especially like it because it sometimes creates the misconception that this was how things still looked by the late 1800s/early 1900s when most of our Polish immigrant ancestors came over. In reality, time marched on, and the map kept changing. By 1807, just twelve years after that final partition of Poland, the short-lived Duchy of Warsaw (Figure 3) was created by Napoleon as a French client state. At this time, Napoleon also introduced a paragraph-style format of civil vital registration, so civil records from this part of “Poland” are easily distinguishable from church records.

Figure 3: Map of the Duchy of Warsaw (Księstwo Warszawskie), 1807-1809. 3

During its brief history, the Duchy of Warsaw managed to expand its borders to the south and east a bit thanks to territories taken from the Austrian Empire, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Map of the Duchy of Warsaw, 1809-1815.4

However, by 1815, following the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the Duchy of Warsaw was divided up again at the Congress of Vienna, which created the Grand Duchy of Posen (Wielkie Księstwo Poznańskie), Congress Poland (Królestwo Polskie), and the Free City of Kraków. These changes are summarized in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Territorial Changes in Poland, 1815 5

The Grand Duchy of Posen was a Prussian client state whose capital was the city of Poznań (Posen, in German). This Grand Duchy was eventually replaced by the Prussian Province of Posen in 1848. Congress Poland was officially known as the Kingdom of Poland but is often called “Congress Poland” in reference to its creation at the Congress of Vienna, and as a means to distinguish it from other Kingdoms of Poland which existed at various times in history. Although it was a client state of Russia from the start, Congress Poland was granted some limited autonomy (e.g. records were kept in Polish) until the November Uprising of 1831, after which Russia retaliated with curtailment of Polish rights and freedoms. The unsuccessful January Uprising of 1863 resulted in a further tightening of Russia’s grip on Poland, erasing any semblance of autonomy which the Kingdom of Poland had enjoyed. The territory was wholly absorbed into the Russian Empire, and this is why family historians researching their roots in this area will see a change from Polish-language vital records to Russian-language records starting about 1868. The Free, Independent, and Strictly Neutral City of Kraków with its Territory (Wolne, Niepodległe i Ściśle Neutralne Miasto Kraków z Okręgiem), was jointly controlled by all three of its neighbors (Prussia, Russia, and Austria), until it was annexed by the Austrian Empire following the failed Kraków Uprising in 1846.

By the second half of the 19th century, things had settled down a bit. The geopolitical map of “Poland” didn’t change during the time from the 1880s through the early 1900s, when most of our ancestors emigrated, until the end of World War I when Poland was reborn as a new, independent Polish state. The featured map at the top (shown again in Figure 6) is one of my favorites, because it clearly defines the borders of Galicia and the various Prussian and Russian provinces commonly mentioned in documents pertaining to our ancestors.

Figure 6: Central and Eastern Europe in 1900, courtesy of easteurotopo.org, used with permission.6

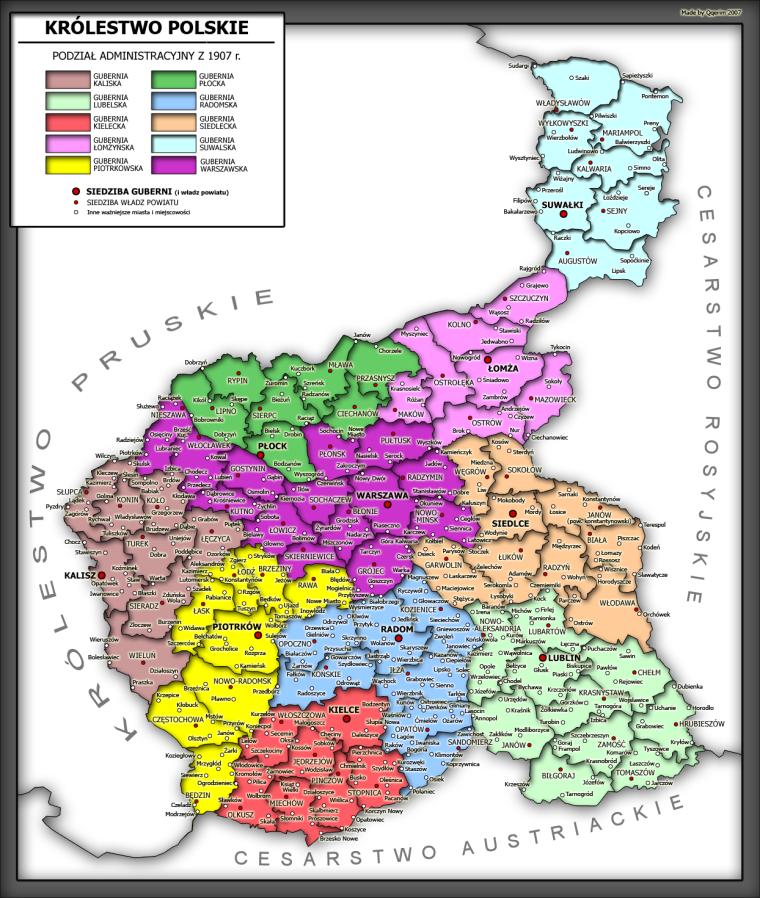

Although the individual provinces within the former Congress Poland are not named due to lack of space, a nice map of those is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Administrative map of Congress Poland, 1907.7 (Note that some sources still refer to the these territories as “Congress Poland” even after 1867, but this name does not reflect the existence of any independent government apart from Russia.)

The Republic of Poland that was created at the end of World War I, commonly known as the Second Polish Republic, is shown in Figure 8. The borders are shifted to the east relative to present-day Poland, including parts of what is now Lithuania, Ukraine, and Belarus. This territory that was part of Poland between the World Wars, but is excluded from today’s Poland, is known as the Kresy.

Figure 8: Map of the Second Polish Republic showing borders from 1921-1939.8

During the dark days of World War II, Poland was occupied by both Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. About 6 million Polish citizens died during this occupation, mostly civilians, including about 3 million Polish Jews.9 After the war, the three major allied powers (the U.S., Great Britain, and the Soviet Union) redrew the borders of Europe yet again and created a Poland that excluded the Kresy, but included the territories of East Prussia, West Prussia, Silesia, and most of Pomerania.10, 11 At the same time, the Western leaders betrayed Poland and Eastern Europe by effectively handing these countries over to Stalin and permitting the creation of the Communist Eastern Bloc.12

To conclude, let’s take a look at how these border changes affected the village of Kowalewo-Opactwo in present-day Słupca County, Wielkopolskie province, where my great-grandmother was born. This village was originally in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, but then became part of Prussia after the second partition in 1793. In 1807 it fell solidly within the borders of the Duchy of Warsaw, but by 1815 it lay right on the westernmost edge of the Kalisz province of Russian-controlled Congress Poland. After 1867, the vital records are in Russian, reflecting the tighter grip that Russia exerted on Poland at that time, until 1918 when Kowalewo-Opactwo became part of the Second Polish Republic. Do these border changes imply that our ancestors weren’t Poles, but were really German or Russian? Hardly. Ethnicity and nationality aren’t necessarily the same thing. Time and time again, ethnic Poles attempted to overthrow their Prussian, Russian or Austrian occupiers, and those uprisings speak volumes about our ancestors’ resentment of those national governments and their longing for a free Poland. As my Polish grandma once told me, “If a cat has kittens in a china cabinet, you don’t call them teacups.”

Sources:

1“Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth at its maximum extent” by Samotny Wędrowiec, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, accessed 9 January 2017.

2 “Rzeczpospolita Rozbiory 3,” by Halibutt, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, accessed 9 January 2017.

3 “Map of the Duchy of Warsaw, 1807-1809,” by Mathiasrex, based on layers of kgberger, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0., accessed 9 January 2017.

4“Map of the Duchy of Warsaw, 1809-1815” by Mathiasrex, based on layers of kgberger, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, accessed 9 January 2017.

5 “Territorial Changes of Poland, 1815,” by Esemono, is in the public domain, accessed 9 January 2017.

6 “Central and Eastern Europe in 1900,” Topgraphic Maps of Eastern Europe: An Atlas of the Shtetl, used with permission, accessed 9 January 2017.

7 “Administrative Map of Kingdom of Poland from 1907,” by Qquerim, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, accessed 9 January 2017.

8 “RzeczpospolitaII,” is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, accessed 9 January 2017.

9 “Occupation of Poland (1939-1945),” Wikipedia, accessed 9 Janary 2017.

10 “Potsdam Conference,” Wikipedia, accessed 9 January 2017.

11 “Territorial changes of Poland immediately after World War II,” Wikipedia, accessed 9 January 2017.

12 “Western betrayal,” Wikipedia, accessed 9 January 2017.

© Julie Roberts Szczepankiewicz 2017

What a comprehensive explanation! Thanks for the great resources too.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Donna! I’m glad you find it helpful.

LikeLike

Absolutely amazing article. Very informative. I would suggest , the only one more map: from II WW showing parts of Poland incorporated into Germany, Generalną Gubernię and Russia. It would be helpful for some immigrants from II WW time. It explains why some Poles were recruited to German army. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generalne_Gubernatorstwo#/media/File:Generalne_gubernatorstwo_1945.png

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the kind words and the thoughtful suggestion, Maciej! You’re right, that’s an important map, as I think many Americans fail to understand the extent of Nazi control of Poland. I chose to omit a detailed discussion of the border changes during and after World War II since the largest wave of Polish immigration to the United States occurred between 1870 and 1914. I found it necessary to discuss the Second Polish Republic primarily because there is often confusion among descendants of Poles born in the Kresy as to why those lands were once Polish but are no longer part of Poland. I think I might save your suggestion for a future blog post.

LikeLike

Julie, thank you very much for this historical geo/political lesson.

Much appreciated, Uncle Fred

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re always welcome, Uncle Fred. Thanks for being a wonderful resource and cousin.

LikeLike

Fascinating article. Well written and clearly explains a lot. Thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Julie, This is helpful, as Robert’s grandparents were first listed as Russian Polish.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you find it helpful, Sarah! 🙂

LikeLike

researched my ancestry and family tree. found distant cousins, relatives in Poland whom also added family tree research. thank you for the map lessons. very useful for looking up just where locations would have been. 😁 http://bluebloodstoindians.blogspot.com/p/polish-hungarian-family-tree.html?m=1

LikeLiked by 1 person

July, this is amazing. One question: is / was the “Austrian Partition” equivalent to “Galicia” (during the full time of the partitions or any portion of that time)? They are interchangeable so far for my genealogy research but I was just wondering if that was generally true.

Thanks for this great blog and all of the work that you do on the FB Group

LikeLike

“Julie” was intended!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Harriet and the Berky and commented:

A detailed history of Poland and its partitions. Fascinating!

LikeLike

A great article. Thank you. A pain but possibly the best thing us genealogists can do is to catelogue where someone was born…in latitude and longitude. That will never change. God Bless you all from Australia. My dad was Lithuanian but his mum was Polish😀!

LikeLiked by 1 person

An excellent article and many thanks for it Julie. Most Poles in Britain came through WWll deportations to the Gulags of Siberia and are from Polish Kresy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Trying to determine if Pierzchala is a common polish name

LikeLike

It’s very rare in that form, but with the diacritic (Pierzchała), it’s fairly common: http://www.moikrewni.pl/mapa/kompletny/pierzcha%25C5%2582a.html

LikeLike

Diane,

I have just discovered the name Pierzchala in my Wisz family tree through Anna Szwagiel (my great-grandmother’s aunt) who married Jozef Pierzchala, they had seven children including Walenty (my 1st cousin 3x removed). My Wisz family was from Trzebownisko and Nowa Wies, Rzeszow, Galicia, and immigrated to Buffalo NY in 1898.

Christine Wisz

LikeLike

My father was born July 1889 (Krakow ?) came to US in 1898 at age 10 went to live in Buffalo NY I have been searching since 2006 for his actual birth certificate. I have all his legal papers for US you mentioned Buffalo my father’s name Nicholas Ignacy Kujawa Changed to Quava when he became naturalized. Any thoughts? Thank you

LikeLike

Hi, Helen, there are some tips for tracing immigrant ancestors back to Poland, here: https://fromshepherdsandshoemakers.com/2018/03/12/a-beginners-guide-to-polish-genealogy-revised-edition/ It’s likely that your father was born in a small village in the vicinity of Kraków rather than the city itself, and you’ll need to determine that precise location. Do you know the names of your paternal grandparents? Those will help you identify your father in Polish records.

LikeLike

Wonderful Article! Just starting to trace my lineage to this area. On the passenger manifests for my grandparents coming over they list home cities of Chaucsin and Hanczy. Unfortunately, this is a transcription from handwriting which is very hard to read. Any advice 🙂

LikeLike

Hi Elizabeth, sorry for the late reply. I suggest joining the Polish Genealogy group on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/groups/50089808265/) and posting a link to those manifests. Experienced eyes might read the locations differently than the indexers did.

LikeLike

Wonderful breakdown! May I link to your site as a resource for Polish genealogy?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course! Thank you! 🙂

LikeLike

What an eye opening article, and so very clearly explained. My ancestors – Krakowski’s – always have ‘Russian Subject’ on their records, which my grandmother took to mean they were in fact Russian. I’ve never had a clear explanation of this meaning. This article helped a lot.

Thank you

PS. I believe their surname had been made up anyway. No wonder we have such difficulties trying to locate people!

LikeLiked by 1 person

very interesting! just starting researching and running into dead ends searching Poland records….now I know why. Do you know how to research names/ spellings and if they are different in records?

drawing a blank with the last name Bokuniewicz (sometimes Bokoniewicz).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello, Renae, I’m glad you enjoyed the post! Bokuniewicz is a valid Polish surname with the following distribution in Poland circa 2002: https://nazwiska-polskie.pl/Bokuniewicz, so you should have no trouble finding it in Poland.

It’s found in indexed records in Geneteka here: http://geneteka.genealodzy.pl/index.php?search_lastname=bokuniewicz&search_lastname2=&from_date=&to_date=&rpp1=&bdm=&w=&op=se&lang=eng

However, Geneteka is incomplete, so if you don’t find your ancestors or specific research targets in this database, that’s why. If you’re just getting started with Polish research, you may not know where in Poland your ancestors were from, and that’s a critical piece of information. The basic method for starting out is outlined here: https://fromshepherdsandshoemakers.com/2018/03/12/a-beginners-guide-to-polish-genealogy-revised-edition/

Finally, name changes are par for the course in genealogy, no matter the ethnicity of your ancestors. You just have to proceed carefully, evaluating each additional piece of information found in a document — e.g. spouse’s name, parents’ names, address, age, place of birth, etc. — so you can be sure that the person described in a given document is the same as the one you’re looking for. Although it deals with some of my Irish ancestors, a helpful blog post on the subject of name changes is found here: https://fromshepherdsandshoemakers.com/2019/04/23/the-walshes-of-st-catharines-digging-deeper-with-cluster-research/

Good luck, and let me know if you need further assistance.

Best regards,

Julie

LikeLike

Any advice of locating a town/village I can’t find a record of? The name is Sychowitz or Sycowicz. At the time of immigration is was probably Russian. (1912).

LikeLike

Maybe Sycewicze, which was in the Russian Empire at that time, and was in Mołodecki county, Wilno province between the wars? It’s in Belarus today. https://be.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%A1%D1%8B%D1%87%D0%B0%D0%B2%D1%96%D1%87%D1%8B This is just a guess, though. I would recommend posting in one of the genealogy groups on Facebook for further assistance and evaluation of your evidence. 🙂

LikeLike

My paternal grandfather was born in Prussia. He was about to be conscripted into the Russian army when his father “bought” a passport and he left for America. Given that, how common is my maiden name – Obst, as a Polish, Catholic surname?

LikeLike

So he was born in Prussia, but migrated to Russia, where he was going to be conscripted? Obst is not what I’d consider a rare surname. You can view the distribution circa 2002 here: https://nazwiska-polskie.pl/Obst

LikeLike

This is fascinating. My great-grandparents listed Poland as their native country on their passenger manifest (1892), but Moscow as the last city they lived in. My Jewish great grandfather was a blacksmith in the Russian army, as I understand it. So, I’m guessing he was conscripted?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, conscription was the rule in the Russian Empire (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conscription_in_the_Russian_Empire), but there’s an interesting article about Jewish conscription, specifically, here: https://www.jewishgen.org/infofiles/ru-mil.txt

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry… just wanted to add to what I wrote before: if Poland didn’t exist, then how/why would they refer to it as their native country on the manifest?

LikeLike

Occasionally you’ll see U.S. documents dated prior to 1918 that refer to “Poland.” Many ethnic Poles, including emigrants, held strong nationalistic beliefs and resented Russian oppression, so they preferred to refer to their homeland as “Poland” even though Poland no longer existed as an independent nation. I have not observed this as commonly with Jewish immigrants, who (in my limited experience with Jewish research) were more likely to simply refer to themselves as ethnic Jews from Russia, even if they were from a part of the Russian Empire that was inhabited predominantly by ethnic Poles. However, I haven’t done that much Jewish research, as I said, so your mileage may vary.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your response! I’ve found the same in my research. I do wonder if it was a mistake on the part of the “scribe” who was creating the manifest. He had indicated Poland as the native country for someone a few lines above my great grandfather – and then just placed ditto marks below to the bottom of the page.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, that makes much more sense! Context is everything. 🙂 Happy researching!

LikeLike

Wow. This article is incredibly eye opening. Recently, I have been researching the history of my family genealogy. My mother’s maiden name is Dyszkiewicz and I’ve only heard vaguely about her grandparents. They definitely had Polish roots, only knew Polish cooking, etc. But that’s about all I knew. I recently began a search down the Dyskiewicz side to find out exactly who and when my great great grandfather and his father came over in 1907 from Bremen, Germany however claimed they were Polish, from Poland, and even found the village name they were a part of. It has brought me so much joy and meaning to my current life. I feel like I have been able to reignite and carry the torch of legacy for this side of my family. This has started a new journey to start learning about Polish history and why did these two men decide to move their entire family to the US at that time. Your findings have really helped me understand the great shifting of the Polish territories. Your quote from your grandmother about calling the kittens “teacups” brought me great laughter. Thank you for your work and sharing this!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Kelly! You sound like a researcher after my own heart — genealogy brings me a great deal of joy, too. I’m so glad that you found this article helpful!

LikeLike

To add to my previous comment, and if I could have your insight as I’m not a natural history buff at all and struggling to comprehend this complex history of my Polish ancestors, through my research I found that the actual passenger list from the Cassel ship in 1907 that brought my great great grandfather and his father here, they claim “Poland” as their country of origin. In other documents I found of these same people after they were here, I find “Prussia” listed. I have also found the village of where great great grandfather said he lived and it was called “Silec”, which I believe still exists in modern day Poland. What do I take of this? Were they more Russian, or from Poland just being swayed in the middle of those border changes?

LikeLike

My first thought is that you might want to double check that manifest you found, as I’d be surprised if their “country of origin” or “last permanent residence” was recorded as “Poland,” since that did not exist in 1907, but I would not be at all surprised if it states “Polish” in the “ethnicity” column. You’re absolutely correct, there’s a town in Poland today called Silec (Schülzen in German) which was formerly located in the East Prussia province but is presently located in Kętrzyn County in the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship of Poland. This would suggest that your family were ethnic Poles living in the Prussian partition, and you would expect to see their nationality noted as “German,” “Prussian,” or (after 1945) “Polish” on records from the U.S. So I’m not clear on your question about the “Russian” identification. Did you find some documents which stated their nationality as Russian?

LikeLike

Thank you for your quick reply! Very enlightening. You are correct, some documents state Germany and Prussian and their nationality and Polish as ethnicity. Your explanation clears up the confusion. Thank you for your insight!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome! Good luck, and happy researching!

LikeLike

My grandfather says he was born in Augustynowo, Poland 1896. His parents documents list Germany and Russia as the country of origin. Last name Mueller. His father born in Słubin, Izbica Kujawska, Kujawsko-Pomorskie, Poland 1874. We can go back 2 more generations and then it stops.

LikeLike

Hi, thanks for this amazing article. It is so helpful. My grandmother came to Australia in 1949, after being in the Butzbach Resettlement Camp. She said she lived near Lwow and said her family was previously Austrian. (from the same place, which makes sense with the earlier maps. On her transport documents, she said she was from Charobrow but i cant find this on a map. I am trying to find her maiden name. All traces prior to immigration are lost.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Eva, I’m glad you found the article to be helpful. Did your grandmother marry in Australia? I don’t know anything about Australian research, but here in the U.S., her marriage record should state her parents’ names, and there should be a church version and a civil version. Her death certificate might also state her parents’ names, if the informant knew them. There may be additional documents that would state parents’ names; Facebook has lots of genealogy research groups and there’s probably one for Australian research that might help you figure out where else to look. As for her place of origin, I’m fairly certain it must be Chorobrów, which was a village located in gmina Chorobrów, Sokał County, in the Lwów voivodeship. It’s presently known as Khorobriv (Хоробрів), Ukraine. You can see it on the map here: https://tinyurl.com/5a6c4tjw Hope this helps. Good luck with your research!

LikeLike

I keep looking for information about Danzig (Gdansk) where my Dad was born in 1925, trying to find family history about Gerhard Erich Paul Greinke, mother Helene Sielaff. Married in Germany in 1952, immigrated to Canada 1954 via the Bremehaven ship. Was it Germany, Poland or at a time when many borders where in turmoil. So much was lost during the war.

This article was perhaps one of the more detailed studies. Thanks!

Diana Greinke

LikeLike

The link to the timelapse video of Europe is broken as the YouTube account no longer exists.

LikeLike

Hi Kay, thanks for the heads-up. I’ve updated the link.

LikeLike

Hola mi nombre es mirta mí abuelo vino con sus documentos que decían que estaban bajo el imperio-Astrohungaro pero el hablaba ucraniano y creo que un poco polaco. Pero no entiendo si los pueblitos de Hruscka, Dolyna y Humnyska también estaban bajo ese imperio? Gracias

LikeLike

Hi Mirta, Jan Bigo’s Galicia gazetteer (available here: https://www.familysearch.org/library/books/records/item/550011-redirection) identifies places that were in the Galicia province circa 1897, and all of these places would have been in the Austrian Empire. A search of this gazetteer does not reveal any places spelled “Hruscka,” but it’s not uncommon to find misspellings of place names in documents. There are a few places that might be close (Hruskie, Hruszówka, etc.), but you may need to do additional research to identify which one is correct.

The same is true for “Dolyna;” there is no place by that name, but there are a number of places called Dolina. Finally, there are three places called Humniska. I hope this helps!

LikeLike

Gracias por tus comentarios , y por tu pronta respuesta , haré otra investigación con esos nombres , el tema es que no tengo conocimiento de tener parientes en los pueblos de Dolina,. Hruskie, y Humnyska con apellidos Mazur, krujoski, kosteski y korol..gracias

LikeLike

Excellent. Thank you.

We currently have Szyman as our family name. On my Father’s baptismal certificate from St. David Parish in Bridgeport, Chicago the name is Szymankowski, but on the Cook County birth certificate it is Szyman! My paternal grandmother’s family name is Radecki and I have a copy of her father’s naturalization paper which lists him a a subject of Germany. The Final Naturalization Oath was filed March 27, 1894 in Cook County, Illinois. Since a person had to have lived in the US for at least 5 years, Joseph Radecki immigrated on or before 1889. He was a blacksmith and must have enjoyed his vodka as he died of cirrhosis of the liver. I would like to know more exactly what city, town or village he emigrated from.

The discussion of nationality versus ethnicity is dramatically confirmed by the Radeckis as they claimed country of origin as Poland in USA census reports.

I have discovered no information whatsoever regarding my paternal grandfather’s parents. I have searched for his birth certificate in Cook County to no avail.

My father’s sister spelled her family name Scyman and I have a copy of my fraternal grandfather’s army discharge paper. His name is spelled Szymantkowski. He was also identified as Szymanski at times.

I have done academic research with colleagues from the Pilsudski University in Warsaw.

LikeLike

Hello Julia. My family has always referred to themselves as Carpatho-Russian or Lemkos. I know my grandmother was born in a small town called: “Ya-shun-ka” (my phonetics) in Poland in 1909. But I remember her saying that the town was destroyed during WWII and was “moved”(??).

Joe Biden just sent troops into Jasionka Poland! The location seems to match and there are some neighboring towns whose names match with what I know of her home town. Also, very small, rural population. Almost 100 years have past since my grandmother lived there and things do change! But is this the same town she would have lived in before she came to the US in 1927? Or is it the relocated, post-WWII version that uses the same name? I wanted to try to match the longitude & latitude coordinates, but couldn’t find them from either 1909 or 1927. (Perhaps because it was such a small “insignificant” town, it never was documented??) If it is the same town & location, is it still Carpatho-Russian(Rusyn)? Or is it now predominantly Polish or German (descendants) as a result of Visla Action of 1947?

LikeLike

Hi Diane, your family was almost certainly from the Galicia region of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a region which is presently divided between southeastern Poland and southwestern Ukraine. There was no independent Poland in 1909 when your grandmother was born, but there was an independent Poland in 1927 when your grandmother left, so the fact that her village was located within the borders of Poland in 1927 is good to know. The Skorowidz miejscowości Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, which is an index of places located in the Second Polish Republic, published circa 1933, identifies 12 places called Jasionka that were in Poland at that time, and Jan Bigo’s gazetteer of Galicia, published in 1918, identifies five of those same places that were specifically within the Galicia region. Of those five places, further research would be needed before I’d be comfortable definitively identifying her village. Most of the relocation that you referred to involved villagers leaving and being resettled in other parts of Poland, often in what is now western Poland, but to my knowledge, those who were resettled did not rename their new villages after their former villages. I think an onsite researcher in that area could assist you further. If you provide your email address through the contact form on this page, I can give you some recommendations for researchers. Good luck!

LikeLike

Thank you Julie, on another note these maps are very interesting for WWII readers as well as other European history readers. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome! 🙂

LikeLike

Flipping heck .

Such a lot of changes to all the countries .

I’m glad it’s Been sort of straightened out .

They really need a settled life .

My Grandmother Marcyanna was born in Galicia .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, some of those border changes didn’t involve any relocation for the people involved, just a new “overlord” when it came to paying taxes! 🙂

LikeLike

Hola me.gustaria saber a quienes se los llamaban o se llaman rutenos?

LikeLike

Hello, Ruthenians are the ancestors of present-day Ukrainians and Belarusians. This article is in English, but you can probably find similar explanations in Spanish. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ruthenians#:~:text=Ruthenian%20and%20Ruthene%20(Latin%3A%20Rutheni,medieval%20and%20early%20modern%20periods.

LikeLike