The sweetest victories are the ones that took the longest time in coming. A couple days ago, I happened upon some documents that fundamentally changed my understanding of my Grzesiak family history, documents I’ve been seeking for many years. So there is some major happy dancing going on in the Szczepankiewicz house today, albeit limited to just one of its residents.

The Grzesiaks of Kowalewo-Opactwo and Buffalo, New York

In a previous post, I wrote a little about the family of my great-grandmother, Veronica (née Grzesiak) Zazycki. Veronica immigrated from the little village of Kowalewo-Opactwo in Słupca County to Buffalo, New York, where she was eventually joined by three of her siblings: Władysław (“Walter”), Tadeusz/Thaddeus, and Józefa/Josephine. Regarding Veronica’s oldest brother, Grandma told me that Walter had married an actress in Poland, whose name Grandma remembered as “Wanda,” but she didn’t want to leave her career, so he left her and came to the U.S. without her. There were no children from this marriage.

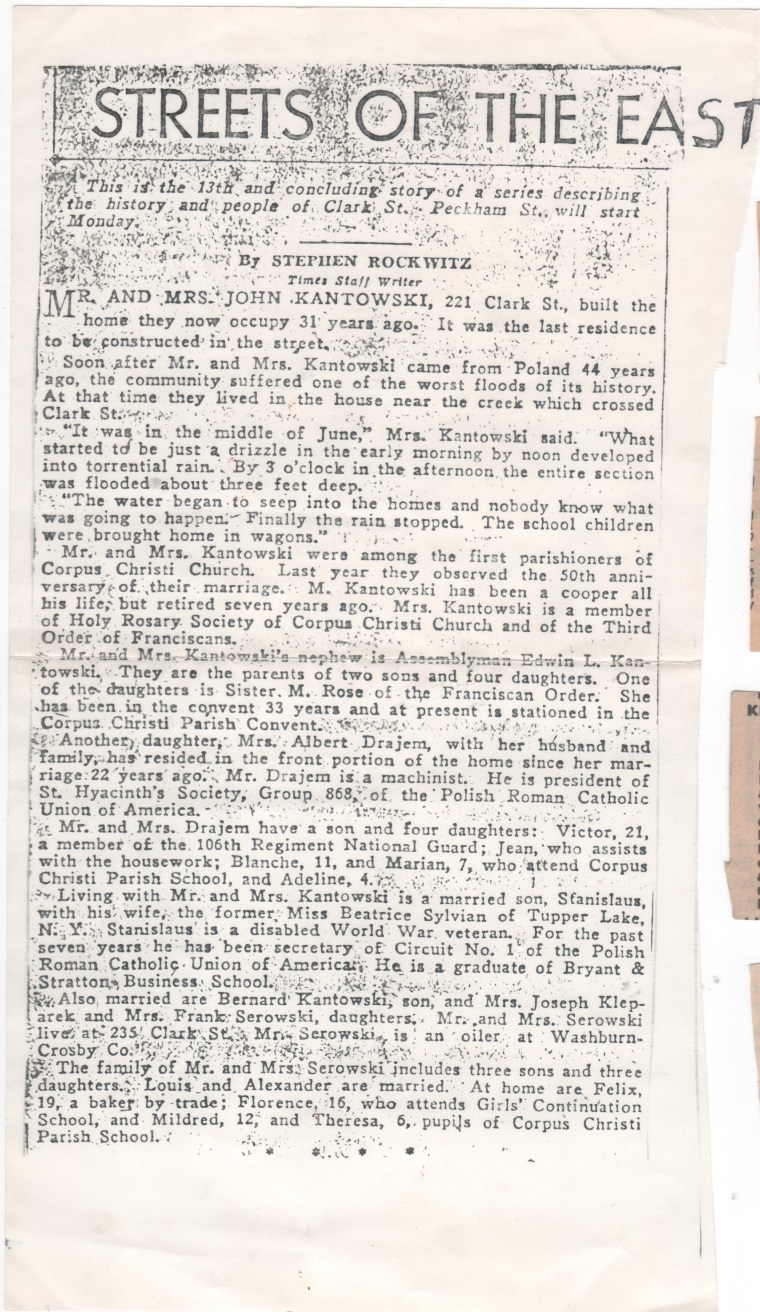

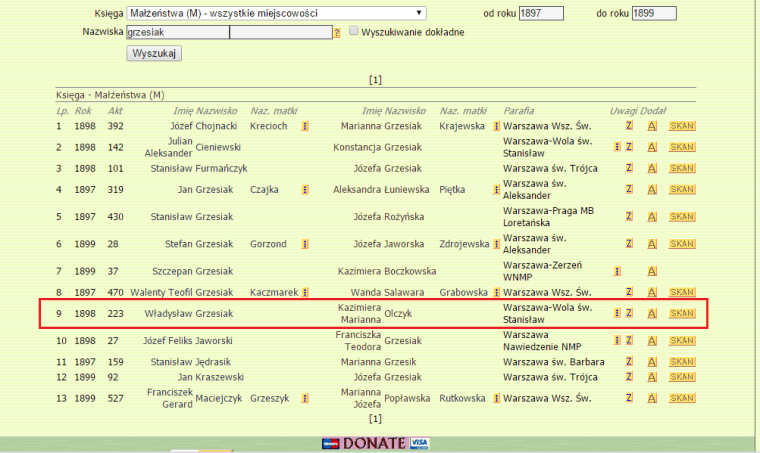

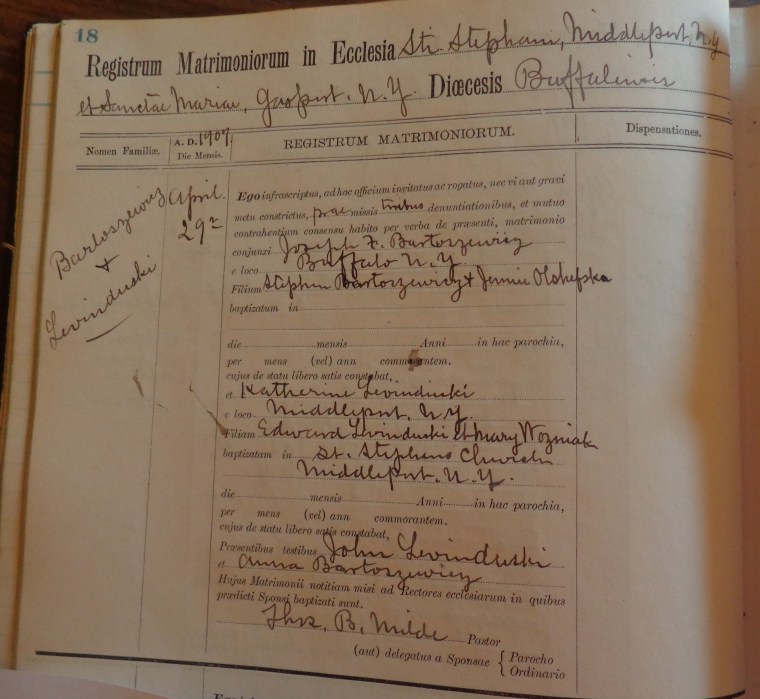

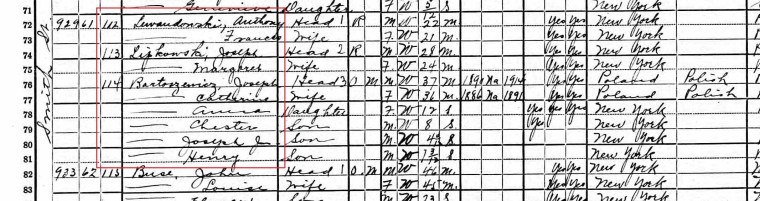

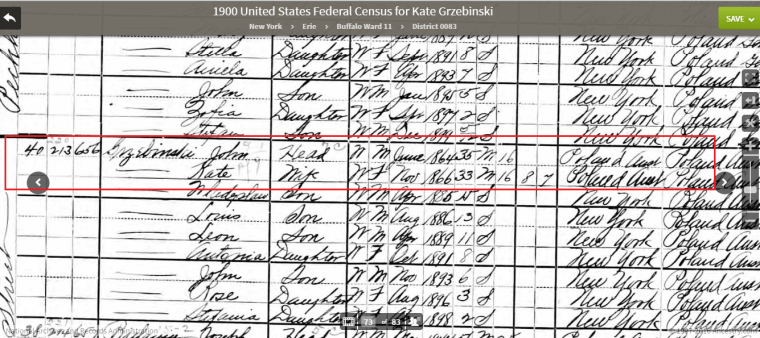

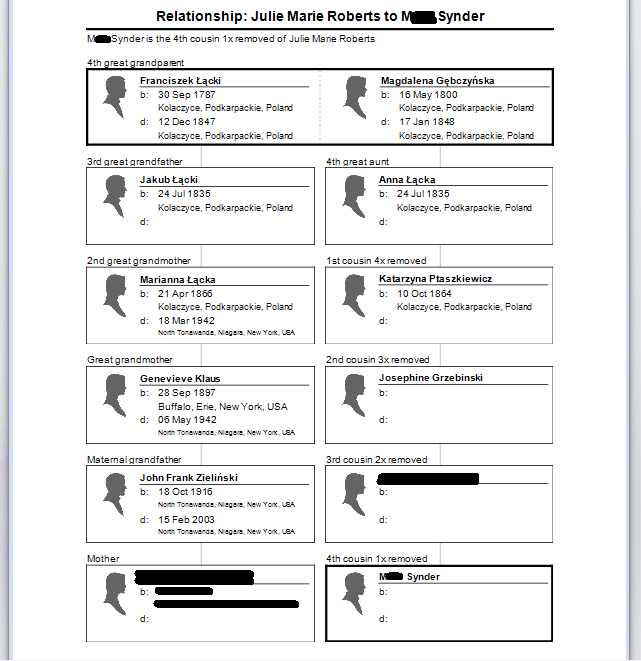

When I began to look for documentation for these family stories, I realized the situation wasn’t exactly as Grandma had portrayed it. The 1900 census (Figure 1) shows the Grzesiak family all living on Mills Street in Buffalo, consisting of patriarch Joseph, sons Władysław and Thaddeus, daughter Jozefa, and daughter-in-law Casimira — Walter’s wife of two years. Clearly, Walter’s wife DID come to Buffalo, rather than staying in Poland while he left without her – but her name was Casimira, not Wanda. The census goes on to state that at that time, she was the mother of 0 children, 0 now living, consistent with family reports.

Figure 1: Extract from the 1900 U.S. Federal Census, showing the Grzesiak family.

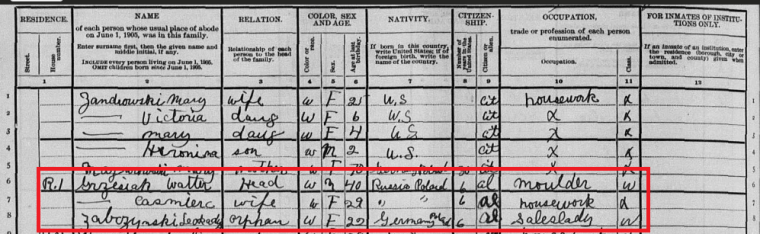

In the 1905 New York State Census (Figure 2), Walter and Casimira were still living in Buffalo, so the marriage lasted at least 7 years. Subsequent records (e.g. the 1940 Census) do indeed show Walter as divorced or a widower.

Figure 2: Extract from 1905 New York State Census showing Walter and Casimira Grzesiak.

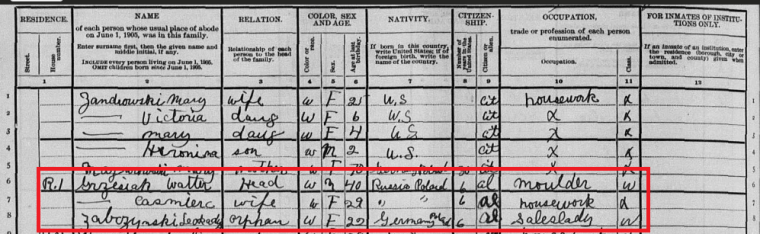

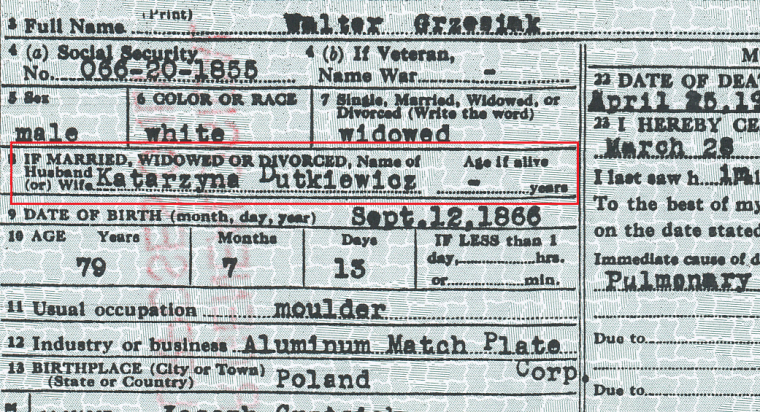

Walter’s death certificate1 reports his ex-wife’s name as “Katarzyna Dutkiewicz (Figure 3), and the informant was his brother, Thaddeus.

Figure 3: Extract from Walter Grzesiak’s death certifcate.

Clearly, Thaddeus made a mistake with the first name, reporting it as Katarzyna (Katherine) instead of Kazimiera/Casimira. So how much faith should we put in his version of her maiden name, Dutkiewicz? Death records are often viewed with some circumspection, since someone other than the deceased is providing the information, and that person might be grieving or in shock. However, it was all there was to go on, and it seemed like it should have been a good start: Name, Kazimiera Dutkiewicz (or similar), born about 1880 (based on those census records), married to Władysław Grzesiak in Poland circa 1898.

The Hunt Is On!

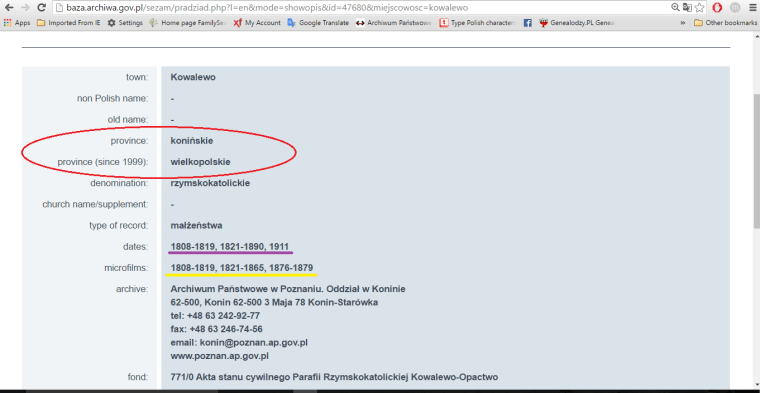

Since Walter Grzesiak was born in Kowalewo-Opactwo, it seemed logical that he would have married somewhere in that vicinity, although not necessarily in that parish. Things get a little tricky with the records for Kowalewo-Opactwo in that time period. Records are not online, or on microfilm from the LDS, so one must write to the Konin Branch of the State Archive in Poznań to request a search. Moreover, although Walter was baptized in Kowalewo, that parish was temporarily closed from 1891-1910. Parish operations were transferred to the church in nearby Ląd, but after 1911, the parishes and their records were separated again. Unfortunately, the archive reported that there was no marriage record in Ląd for Władysław Grzesiak, or for any of his siblings, during this period.

Initially, this finding didn’t concern me too much. It’s traditional for a couple to marry in the bride’s parish, so this suggested merely that Kazimiera was from some other parish in the area. So how does one find a marriage in the Poznań region, when one has no idea what parish the couple married in? The Poznań Marriage Project, of course. For those who might be unfamiliar with this resource, the Poznań Project is an indexing effort conceived by Łukasz Bielecki, which is intended to include all existing marriage records for the historic Poznań region from 1800-1899. Currently, the project is estimated to be at least 75% complete, so there was a good chance I’d be able to find Walter and Casimira’s marriage in there. Frustratingly, there were no good matches, so I assumed that their marriage record must be among the 25% of existing records that remain unindexed. At this point, finding it would be like searching for the proverbial needle in a haystack. I put this on the back burner and went back to more productive research on other family lines.

Until two days ago.

My Breakthrough

It seemed like a perfectly ordinary Wednesday afternoon. I paid bills, ran some errands, took the cat to the vet, and sat down to check e-mail. But if you’re like me, some small part of your brain is always thinking about genealogy, and suddenly it dawned on me: the family story was that Casimira was an actress. How could she have been an actress in a small village with a couple dozen farms? She must have been from a big city — Warsaw!

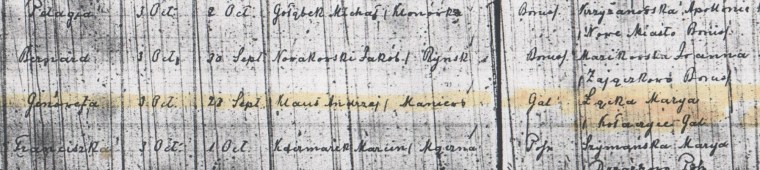

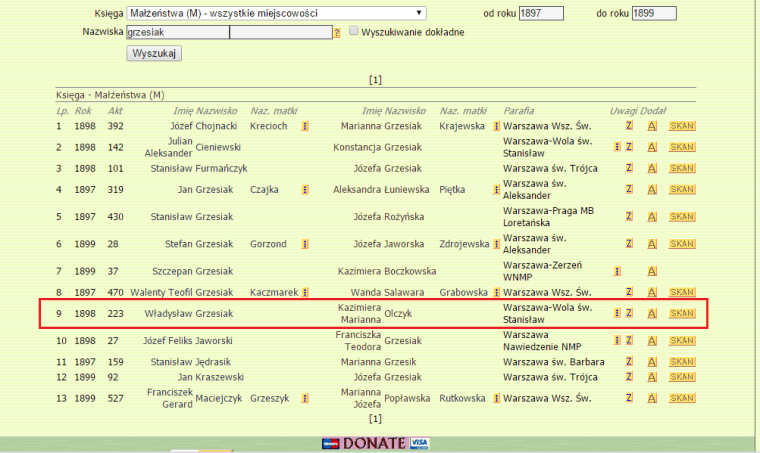

Immediately, I went to Geneteka, my favorite database for indexed vital records from all over Poland. Normally, I advise people to use documentation from U.S. sources to determine where their ancestors came from before they start randomly searching records in Geneteka, but desperate times call for desperate measures, and I had a pretty specific idea of what I was looking for. But would the record be there? Geneteka is not complete — it’s a brilliant, ambitious idea, and new indexes for different parishes and different time periods are constantly being added, but it still represents only a fraction of the vital records available in the tens of thousands of parishes and civil registries across Poland. In this case, my hunch paid off, and Geneteka came through for me. I was stunned, absolutely stunned, when I saw what had to be their marriage record (Figure 4):

Figure 4: Geneteka search results for Grzesiak marriages in Warszawa between 1897 and 1899.

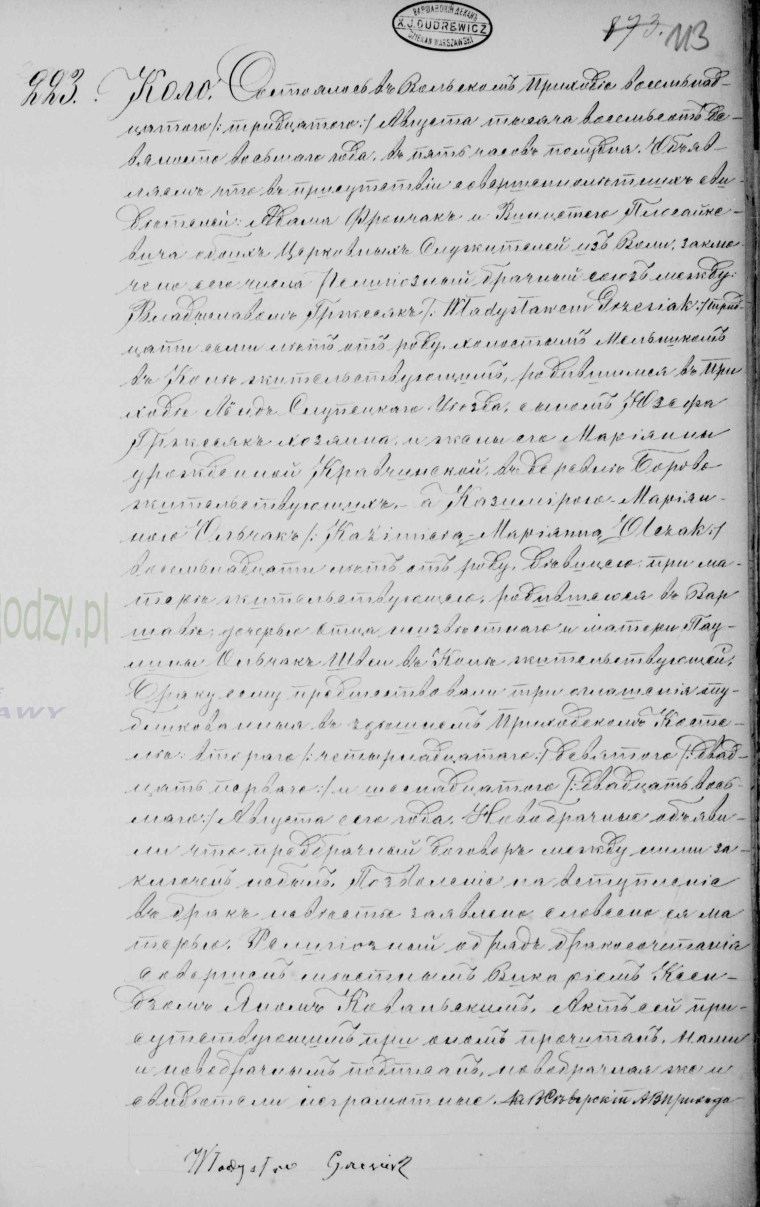

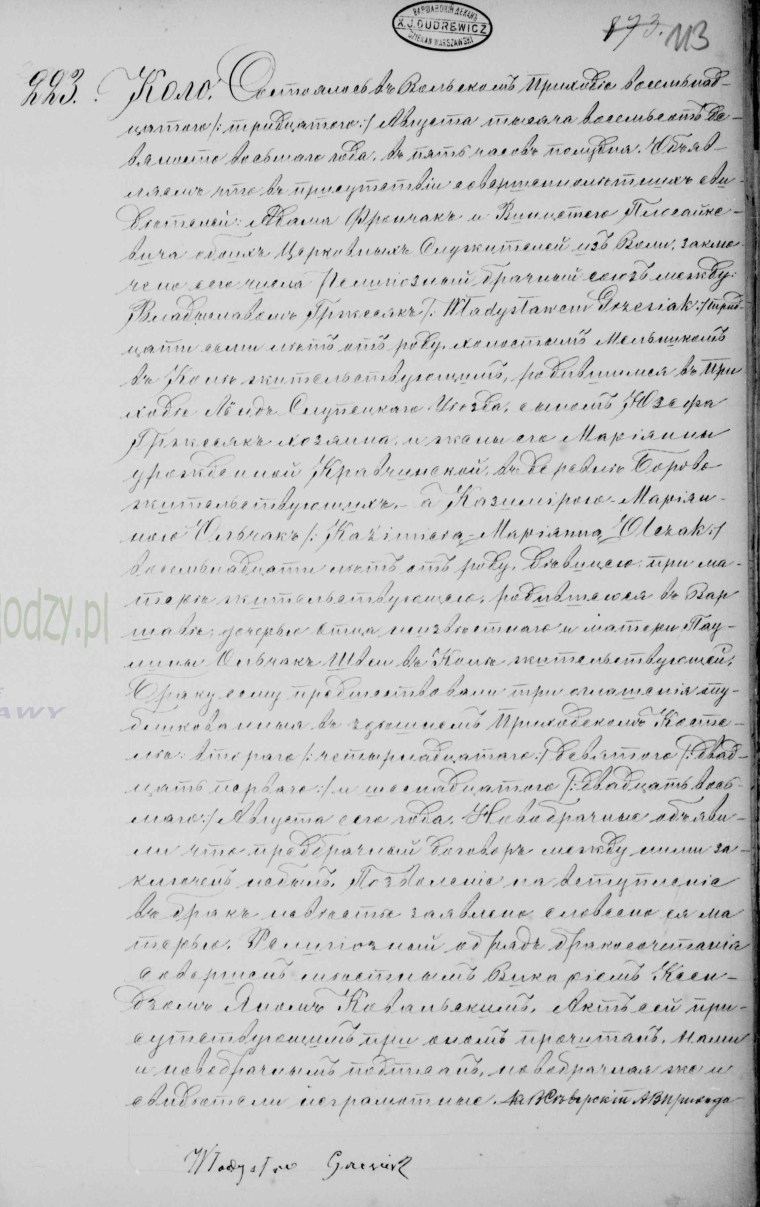

I hit “skan” to get a copy of the record itself (isn’t Geneteka great?!) and here it is, in all its glory:

The record is in Russian, because Warsaw was in the Russian Empire in 1898 when the event took place, so here’s my translation:

“223. Koło. It happened in Wola parish on the eighteenth/thirtieth day of August in the year one thousand eight hundred ninety-eight at five o’clock in the afternoon. We declare that, in the presence of witnesses Adam Franczak and Wincenty Płocikiewicz, both ecclesiastical servants of Wola, on this day was contracted a religious marriage between Władysław Grzesiak, age thirty-seven, miller of Koło residing, born in Ląd, Słupca district, son of Józef Grzesiak, owner, and his wife Maryanna née Krawczyńska, in the village of Borowo residing, and Kazimiera Marianna Olczak, age eighteen, single, with her mother residing, born in Warsaw, daughter of an unknown father and mother Paulina Olczak, seamstress, in Koło residing. The marriage was preceded by three readings of the banns on the 2nd/14th, 9th/21st, and 16th/28th days of August of the present year. The newlyweds stated that they had no prenuptial agreement between them. Permission was given orally by those present at the ceremony. The religious ceremony of marriage was performed by the Reverend Jan Kowalski. This document, after being read aloud, was signed by us and by the groom because the witnesses state that they do not know how to write.”2

Let’s break this down a bit. First, the double dates are often confusing to those who aren’t familiar with the format of Polish civil records, but they’re a result of the fact that Poland and Western Europe adopted the Gregorian calendar while Russia and the Eastern Europe continued to use the old Julian calendar. In order to have these records be clear to everyone, both dates were included on legal documents like this. The second, later date is the date according to the Gregorian calendar, which we would go by.

Second, Kazimiera’s name isn’t Dutkiewicz, as expected — but we’ll worry about that in a minute. The date of the marriage (1898) is correct, as is the groom’s name, and parents’ names. His age is a bit off (he should only be 30, not 37), but it’s not unusual for ages reported in these records to be very much “ballpark estimates.” Walter was actually born in Kowalewo, not Ląd, but if you recall, the parish functions had been transferred from Kowalewo to Ląd at this time, so perhaps this can be interpretted as a reference to that.

Getting back to Kazimiera, her age (18) matches with what we expected based on U.S. records. The priest doesn’t mention her budding theatrical career, but perhaps her star had not yet risen very far (if it ever really rose at all). So this is clearly the right marriage record. But how did we get from Olczak to Dutkiewicz?

The answer lies again in the indexed records of Geneteka (Figure 5):

Figure 5: Geneteka search results for marriage records with surnames Olczak and Dutkiewicz between 1880 and 1900:

It appears that shortly after Kazimiera’s birth in 1880, her mother Paulina married Tomasz Dutkiewicz. Whether Tomasz Dutkiewicz ever legally adopted Kazimiera is doubtful, but this certainly explains why she might have at least informally used the name of her step-father as her own.

But Wait, There’s More!

So all this is nice, right? But why is a marriage record for a great-granduncle really THAT exciting? As I mentioned, my great-grandmother Veronica emigrated along with three siblings, Walter, Thaddeus and Josephine. What we didn’t know until I began researching records from Poland, was that there were two additional siblings — Konstancja3 and Pelagia4 — who did not emigrate. No descendant of the Grzesiak family in the U.S. that I interviewed was aware that these sisters existed. The Konin Branch of the State Archive in Poznań had no record of marriage for either of them, and I was planning to write again to request a search for their death records, assuming they might have died before reaching a marriageable age. However, I noticed that there was a marriage record for a Konstancja Grzesiak on the same page of Geneteka search results (Figure 4, result 2) that gave me Walter’s marriage record! Sure enough, the marriage record5 reveals that Konstancja is the daughter of Józef Grzesiak and his wife, Marianna née Krawczyńska, residing in the village of Ląd.

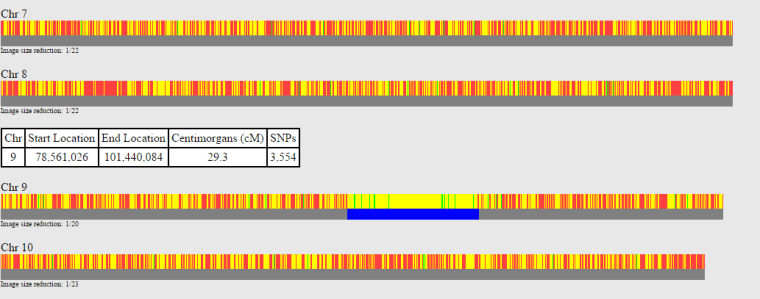

Unfortunately, I still can’t find a birth record for Pelagia, and it’s still possible that she died before reaching a marriageable age. But the implications of these new data are tremendous for me. My great-grandmother arrived in the U.S. in March of 1898,6 and in June and August of that same year, her sister and brother each married in Warsaw, prior to most of her family joining her in Buffalo in 1900, while the one married sister stayed behind in Poland with her family in Warsaw. Wow! A little further digging confirmed that Konstancja also had children (Figure 6):

Figure 6: Geneteka search results for birth records in Warszawa mentioning surnames Cieniewski and Grzesiak:

So I might have cousins in Poland from this Cieniewski line! However, it’s interesting that there are only two births. Birth records for this parish, St. Stanislaus, Bishop and Martyr, and St. Adalbert, in the Wola district of Warsaw, are indexed from 1886 to 1908 without any gaps. Therefore one might expect to see more than two children born between their marriage in 1898 and 1908 when the records end. There is no evidence that they immigrated to Buffalo, no good matches in U.S. census records for this family in Buffalo or anywhere else. So where did they go?

The Grzesiaks of Kowalewo-Opactwo, Warsaw, Buffalo, and Borowo

One clue, in Walter’s marriage record, might point the way. It stated that he was the son of “Józef Grzesiak, farmer, and his wife Maryanna née Krawczyńska, in the village of Borowo residing” Borowo is new to me. This is the first time this place has been mentioned in connection with my family. And unfortunately, there are at least 20 places in Poland today by that name. But if Borowo was where her parents were living at the time of Konstancja’s marriage, maybe that’s where she and her young family eventually went to live. So which Borowo is correct?

Well, Konstancja’s marriage record, from just two months earlier, states that her parents were residing in Ląd. That, and the fact that there were no good matches for a place called Borowo that’s very close to Warszawa, suggests that this may be the correct place, Borowo in Konin County, about 22 miles east of the Grzesiak’s previous home in Kowalewo-Opactwo:

According to the Skorowidz Królestwa Polskiego, a nice period gazetteer of Russian Poland published in 1877, the village of Borowo belongs to the Roman Catholic parish in Krzymów, so that’s where we can look for records. Records are online and on microfilm, but only from 1808-1884, which doesn’t help us any with finding additional births to Konstancja and Julian Cieniewski after 1900. However, the Branch Archive in Konin has birth records up to 1911, so this is an obvious next step to take.

The Old Mill, Revisited

There’s one other really cool connection I’d like to make before I sum things up. In my previous post about my Grzesiak family, I mentioned my grandmother’s recollection that her mother Veronica’s family owned a grain mill near the parish church. Try as I might, I couldn’t find any reference to Veronica’s father being a miller. However, when I visited Veronica’s birthplace of Kowalewo-Opactwo on a trip to Poland last year, I was amazed to see this old windmill, missing its vanes, in close proximity to the church, exactly as Grandma described. So I found it fascinating that Walter’s marriage record described him clearly as a miller, even though a more general term (“хозяин,” meaning “owner,” but seemingly used as a non-specific synonym for “farmer” or “peasant”) was again used to describe his father, Józef. This makes me more convinced that the mill in the photo actually was a place associated with Veronica’s family. Maybe her father didn’t own the mill, maybe he just worked for the miller — but between the existence of this mill where it should be, based on Grandma’s story, and the fact that her uncle Walter was described as a miller, I think there’s good reason to believe that this was the mill that Grandma’s story referred to.

That’s a Wrap

So what general research insights can be gained from this?

-

Once again, my ancestors were more mobile than I expected them to be — and yours might be, too.

When I began my research, I really thought I’d find “the” ancestral village for each surname line and be able to go back for many generations in that same village. Time and time again, that seems to be the exception, rather than the rule. I was so blinded by my expectation that Walter would have met his bride some place near to where he was born, that I overlooked obvious resources, like indexed records for Warsaw on Geneteka, because it seemed too improbable. Logic requires us to search in the obvious places first — those associated with the family. But when searching in the obvious places doesn’t pan out, it’s time to think outside the box.

2. Family stories can sometimes hold the key.

If you are among the oldest generation in your family, it’s not too late to write down everything you remember from older relatives, for the next generation. But if you still have any older relatives remaining, talk to them! My third cousin and research collaborator, Valerie Baginski, told me that her grandmother always said that the family came from Warsaw, rather than Poznań, which was my family’s version of the story. Once we figured out that our Grzesiaks’ ancestral village was Kowalewo-Opactwo, closer to Poznań than Warsaw, we dismissed that mention of Warsaw. Since Warsaw was a bigger city than Poznań, we chalked up this discrepancy to our ancestors’ tendency to paint their place of origin with a broad brush, referencing the closest big city. Now we realize that it’s quite possible her great-grandmother mentioned Warsaw because she was one of the younger siblings who may have lived there for a time, while my great-grandmother mentioned Poznań because she was the first one to leave Poland, and may never have gone to Warsaw with the others.

3. Pay your dues.

This last “insight” is a shameless plug for Geneteka, the database for indexed Polish vital records that enabled me to find my Grzesiaks in Warsaw. For those of you who might be unfamiliar with it, Geneteka is a project sponsored entirely by volunteers from the Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne (PTG, or Polish Genealogical Society), in Poland. Although all the indexing and photographing of vital records (for Geneteka’s sister site, Metryki, which I wrote about previously) is done by volunteers, funds are still required to pay for servers to host the websites. If you’ve used Geneteka and found it helpful to you, please consider making a donation to the PTG. Let’s help them to help us find our ancestors!

Walter’s marriage record was a puzzle piece that’s been missing for a long, long time. It just goes to show you that you never know when that great idea will hit, or when serendipity will strike, so keep chipping away at those brick walls. Stay thirsty, my friends.

Sources:

1New York, Department of Health, Division of Vital Statistics, County of Erie, City of Buffalo, Death Certificates, #2600, Death certificate for Walter Grzesiak, 25 April 1946.

2“Akta stanu cywilnego parafii rzymskokatolickiej sw. Stanislawa i Wawrzynca w Warszawie,” Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne, Metryki.genealodzy.pl: Projekt indeksacji metryk parafialnych (http://metryki.genealodzy.pl/), 1898, Malzenstwa, #223, record for Wladyslaw Grzesiak and Kazimiera Marianna Olczak, accessed on 17 August 2016.

3Roman Catholic Church, Sts. Peter and Paul the Apostles Parish (Kowalewo, Słupca, Wielkopolskie, Poland), Kopie księg metrykalnych, 1808-1879, 1872, births, #5, record for Konstancja Grzesiak.; FHL #1191028 Items 1-4.

4“Akta stanu cywilnego Parafii Rzymskokatolickiej Kowalewo-Opactwo (pow. slupecki)”, Narodowego Archiwum Cyfrowego, Naczelnej Dyrekcji Archiwów Panstwowych, Szukajwarchiwach (Szukajwarchiwach.pl), Ksiega urodzen, malzenstw i zgonów, 1869, births, #48, record for Pelagia Grzesiak, accessed on 21 June 2016.

5“Akta stanu cywilnego parafii rzymskokatolickiej sw. Stanislawa i Wawrzynca w Warszawie “, Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne, Metryki.genealodzy.pl: Projekt indeksacji metryk parafialnych (http://metryki.genealodzy.pl/), 1898, Malzenstwa, #142, record for Julian Aleksander Cieniewski and Konstancja Grzesiak, accessed on 18 August 2016.

6Ancestry.com, Baltimore, Passenger Lists, 1820-1948 and 1954-1957 (Provo, UT, USA, Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006), http://www.ancestry.com, The National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Washington, D.C.; Records of the US Customs Service, RG36; NAI Number: 2655153; Record Group Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004; Record Group Number: 85, record for Veronika Gresiak, accessed on 21 July 2016.

Featured Image:

Wodzinowski, Wincenty. Wesele. Digital image.Http://muzeuminstrumentow.pl/. Muzeum Ludowych Instrumentów Muzycznych W Szydłowcu, 18 Sept. 2015. Web. 18 Aug. 2016. This painting from 1896 seemed very fitting for my cover photo, since it depicts a wedding celebration very close to the time when Walter and Casimira married.

© Julie Roberts Szczepankiewicz 2016