Note: This story was originally published in the Spring 2017 issue of Rodziny, the journal of the Polish Genealogical Society of America. With their permission, I’m publishing it again here, with the intention of following it up with some new data that I’ve obtained since it was published.

Recently I got some exciting new autosomal DNA test results for my “Uncle” (mother’s maternal first cousin), Fred Zazycki. Uncle Fred generously consented to provide a saliva sample for autosomal DNA testing through Ancestry, which is really an incredible gift. Why is it better for me to have his DNA tested in addition to my own? Let’s quickly review some basic concepts in genetic genealogy.

The ABCs of DNA

Each of us has 23 pairs of chromosomes located in the nucleus of almost every cell in the body. These chromosomes contain the genetic material (DNA) that makes us unique individuals. Of these 23 pairs of chromosomes, 22 pairs are called autosomes, and the final pair are the sex chromosomes. For men, the sex chromosomes are an X inherited from the mother and a Y inherited from the father. Women inherit two X chromosomes, one from the mother and one from the father.

One copy of each of the 22 paired autosomes comes from the mother, and one from the father, so roughly half our genetic material comes from each parent. Each parent’s genetic contribution gets cut in half with each successive generation, so although I inherit half my DNA from my mother, I only inherit a quarter of my DNA (on average) from each of my maternal grandparents, and only 1/8 of my DNA (on average) from each of my maternal great-grandparents. If we extend this further, each of us has 64 great-great-great-great-grandparents, and each of them will only contribute 1/64 of our genetic makeup, or about 1.563%, on average. However, due to a process called recombination that affects the way bits of DNA are inherited, these are only statistical averages. In practice, one might inherit a bit more or a bit less from any given ancestor, and all of us have many ancestors from whom we’ve inherited no DNA at all.

For this reason, it’s important to try to test the oldest generations in a family first. Since Uncle Fred is one generation closer than I am to our immigrant ancestor, John Zazycki, Uncle Fred will have inherited an average of twice as much DNA from John Zazycki as I did. This means that his DNA “looks back” into the family tree a generation further than mine is able to.

The Zarzycki and Gruberski families of Bronisławy and Błędów

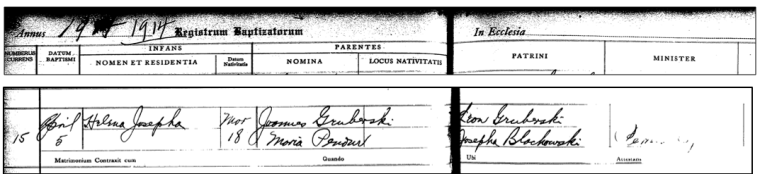

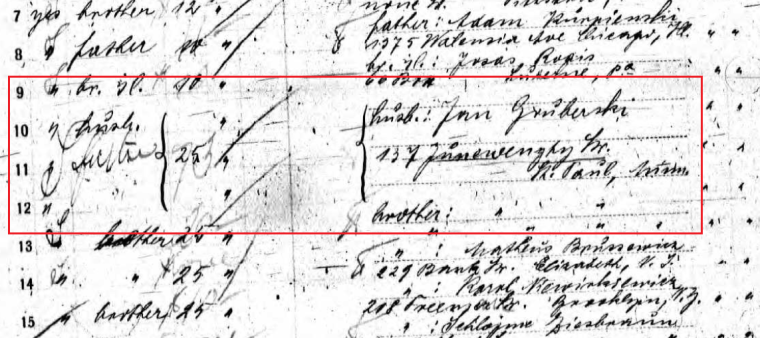

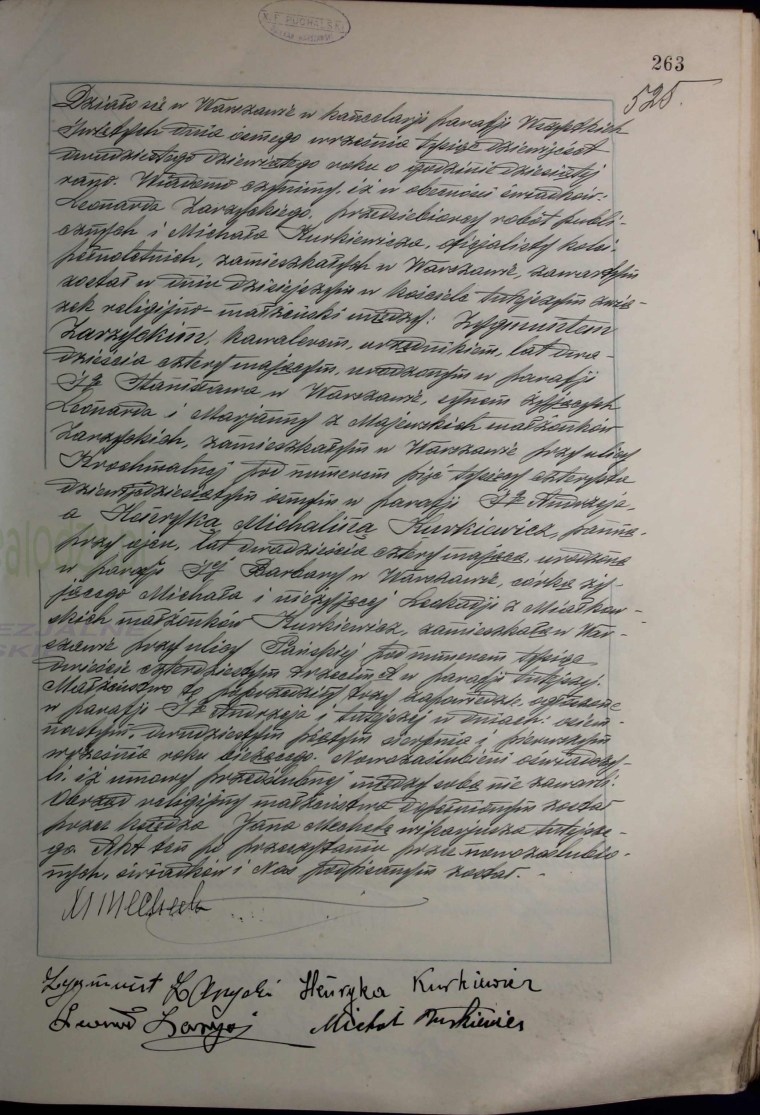

Almost as soon as Uncle Fred’s DNA test results posted, and before I’d even had a chance to look at them, I already had a message in my Ancestry inbox from a DNA match who wanted to investigate the connection. The DNA match,”Cousin Jon,” has a family tree on Ancestry which included a surname I recognized: Gruberski. My great-grandfather John Zazycki had an oldest sister, Marianna Zarzycka, who married Józef Gruberski in 1874 in Rybno (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Marriage record from the parish in Rybno, Sochaczew County, for Marianna Zarzycka and Józef Gruberski, 25 October 1874.1

A full translation of this record is provided in the footnotes, if you’re really interested in reading the whole thing.

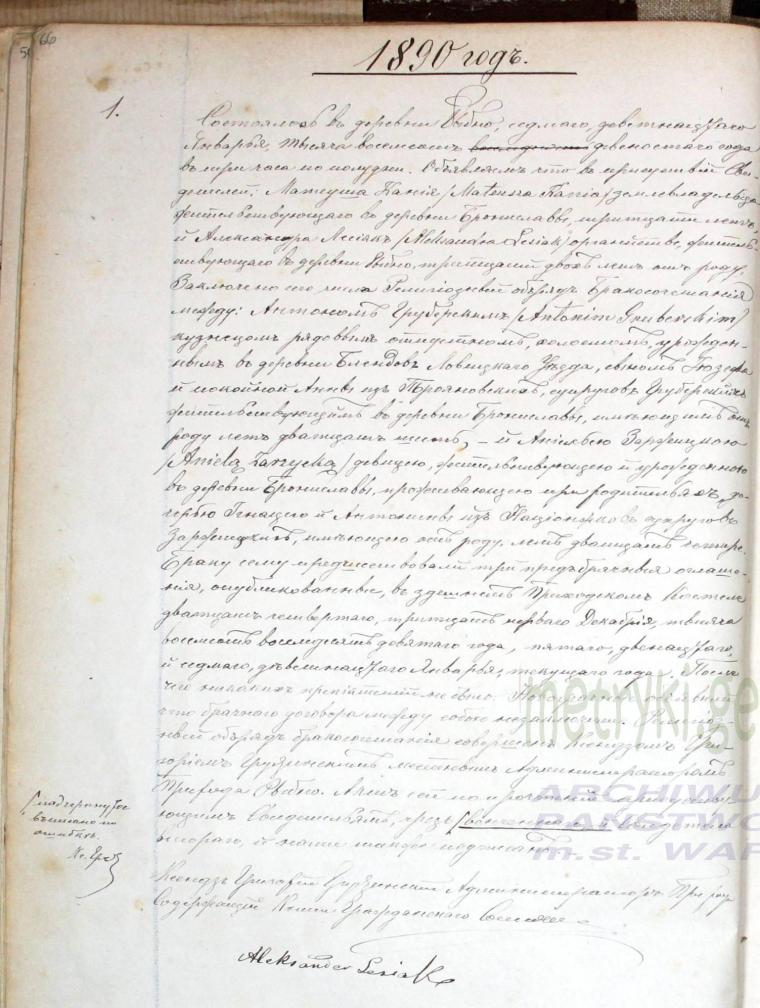

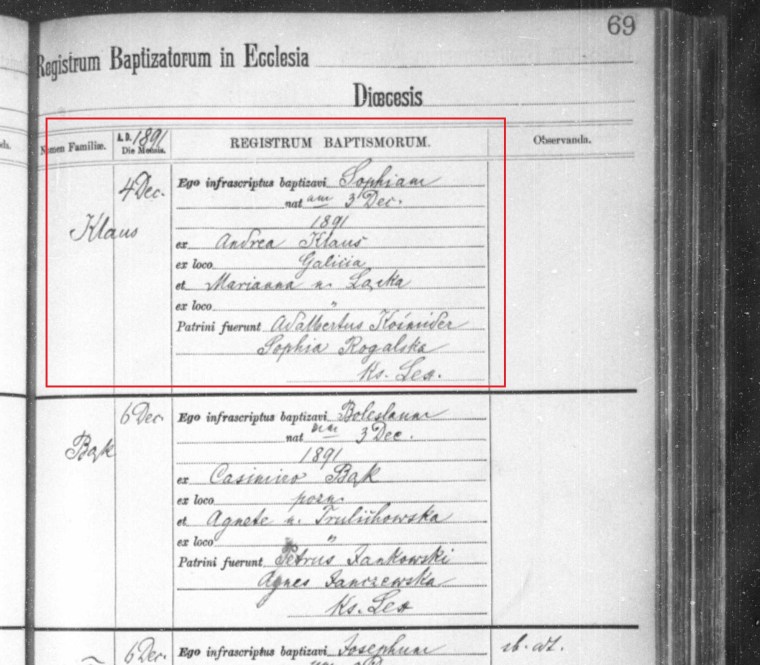

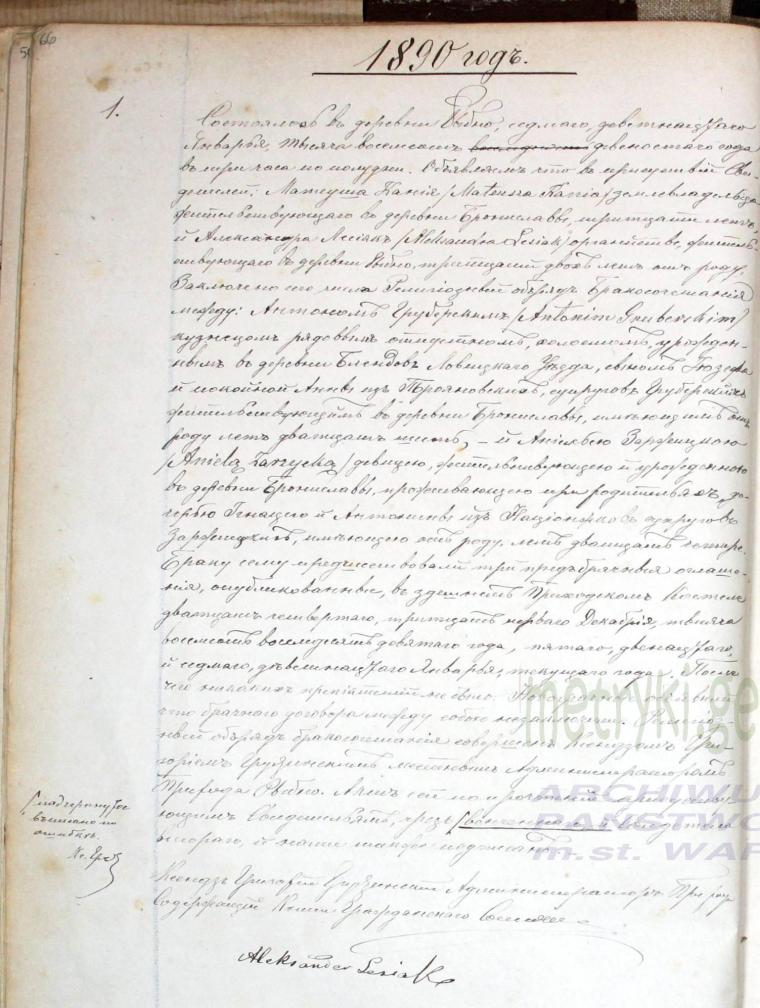

From this record and from the parish records in Łowicz, we know that Józef Gruberski was a 40-year-old widower when he married 24-year-old Marianna Zarzycka. His first wife, Anna Trojanowska, had died four years earlier, and he came into this second marriage with four children. The records of Rybno also reveal that the paths of the Zarzycki and Gruberski families crossed in other ways besides just this marriage. In 1890, Józef Gruberski and Anna Trojanowska’s third son, Antoni Gruberski, married Aniela Zarzycka. Aniela was the younger sister of Antoni’s step-mother, Marianna (née Zarzycka) Gruberska. (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Marriage record from the parish in Rybno, Sochaczew County, for Aniela Zarzycka and Antoni Gruberski, 19 January 1890.2

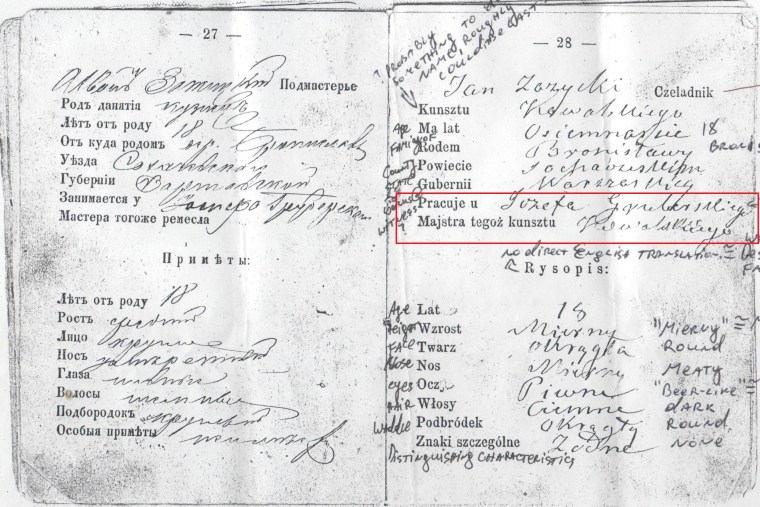

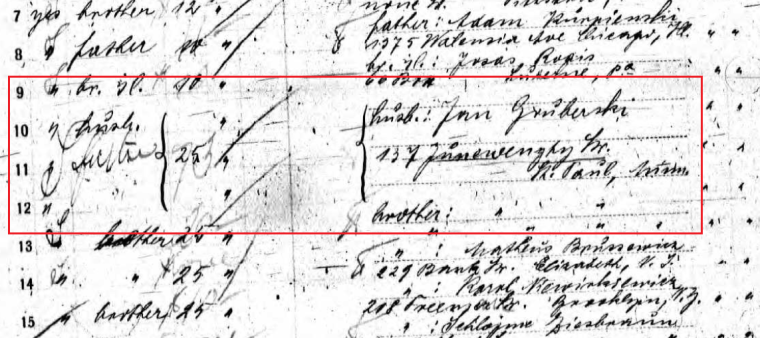

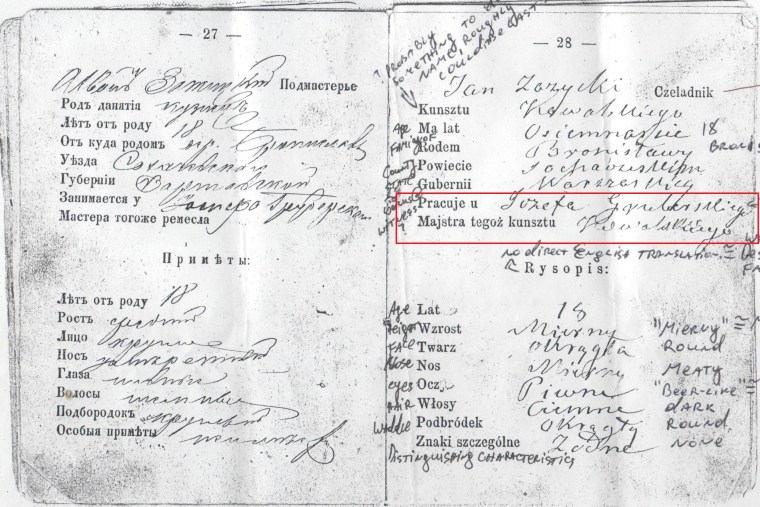

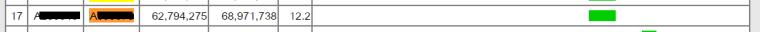

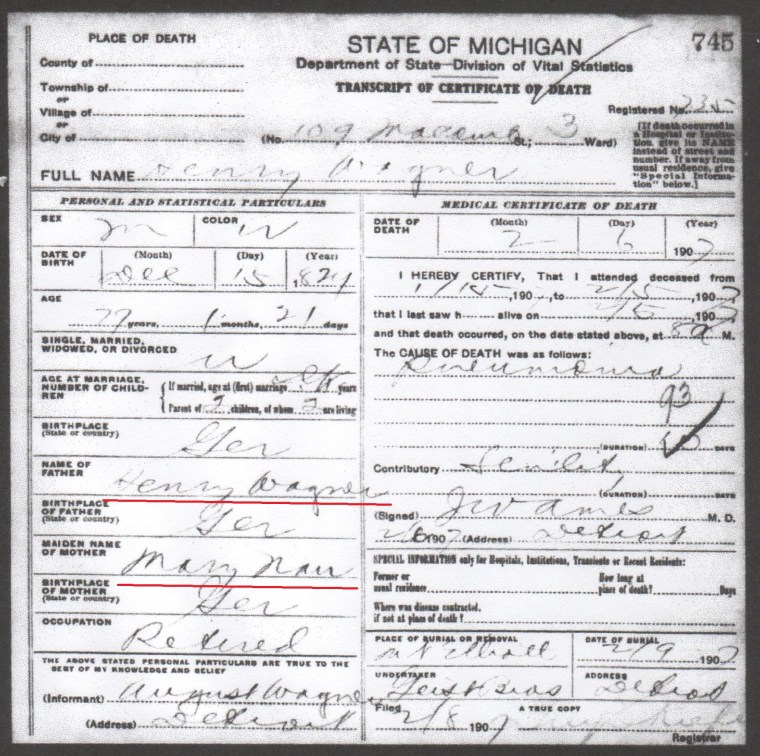

For my great-grandfather Jan Zarzycki, Józef Gruberski was not only husband to his sister Marianna and father-in-law to his sister Aniela, he was also the boss. Józef Gruberski was the master blacksmith under whom Jan had apprenticed. We know this because one of the documents which Jan brought with him from Poland, which was handed down in our family, was an identification booklet that included basic biographical information written in Russian and Polish. (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Identification booklet from Russian Poland for Jan Zażycki.3

In our family, my grandmother’s brother, Joseph, fondly known as Uncle J, was the one who inherited the book from his father, Jan Zażycki. He, in turn, passed it down to my cousin, John, who is Jan Zażycki’s namesake. Consequently, I don’t have the actual book in my possession, but my cousin kindly made a photocopy of some of the pages for me, which included notes from a translator. Some of these aren’t especially accurate, but I don’t have a copy without the notes, so we’ll overlook that part. The interesting thing to note in this context is the part highlighted in red, that states, “Pracuje u Józefa Gruberskiego/Majstra tegoż kunsztu kowalskiego.” This tells us that Jan Zażycki was a blacksmith who was working for Józef Gruberski, master of the blacksmithing craft. The word “czeladnik” in the corner next to Jan’s name means “journeyman,” which would suggest that Jan had completed his training and was now fully qualified to be employed as a blacksmith.

Matchmaker, Matchmaker….

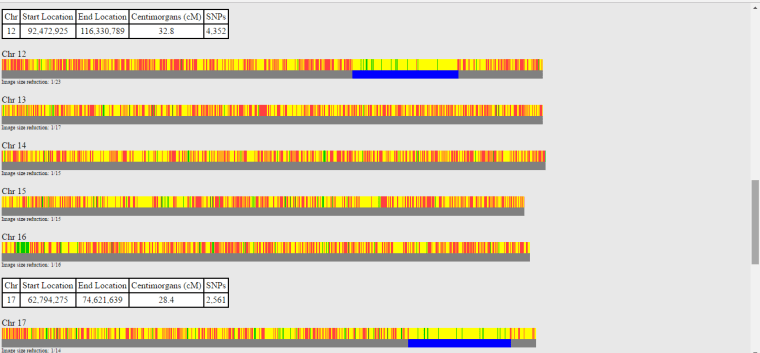

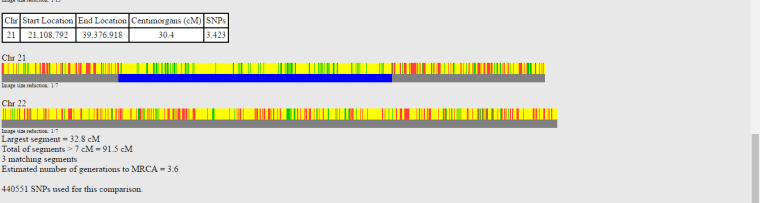

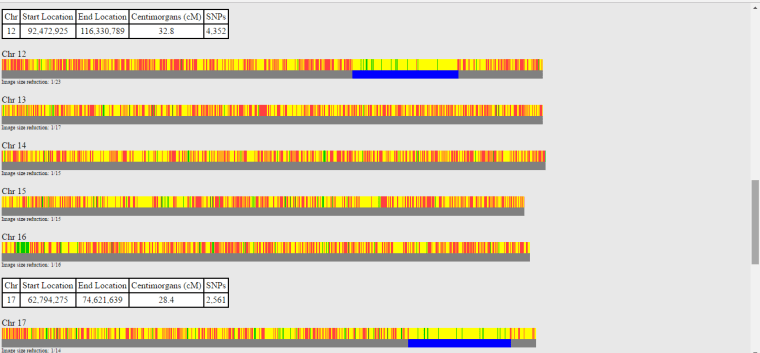

Given all the ways in which the Zarzycki family and the Gruberski family had intertwined, it seemed very likely that this must be how Uncle Fred’s new DNA match was connected to our family. So what do we know about the match itself? Well, GEDmatch reports that it consists of substantial matches on Chromosome 12 (32.8 cM), Chromosome 17 (28.4 cM) and Chromosome 21 (30.4 cM), for a total of a whopping 91.5 cM, which is fantastic, given that this is to a cousin previously unknown to the family (Figures 4a and 4b).

Figure 4a: GEDmatch Autosomal Comparison Between Uncle Fred and Cousin Jon. Green = base pairs with full match, yellow = base pairs with half match, red = base pairs with no match, and blue = matching segments > 7 cM (centiMorgans, a measure of genetic distance).

Figure 4b:

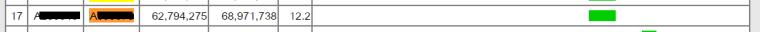

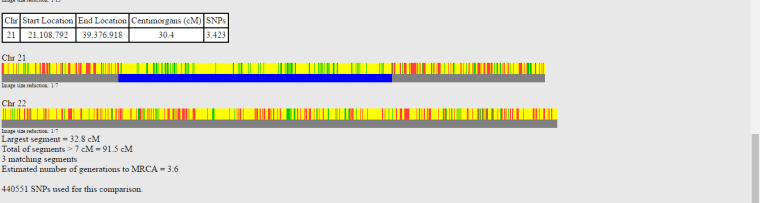

GEDmatch estimates 3.6 generations to the MRCA (Most Recent Common Ancestor) between Uncle Fred and Cousin Jon. Interestingly, when I checked my own matches, I also match Cousin Jon, although the match is much smaller. I ran a GEDmatch Segment Triangulation, which verified that all three of us do share a common segment consisting of 12.2 cM on Chromosome 17 (Figure 5):

Figure 5: GEDmatch Segment Triangulation graphic showing start and stop points for the matching segment shared by Uncle Fred, Cousin Jon and me.

In my case, GEDmatch estimates 5.1 generations to MRCA, even though I’m only one generation away from Uncle Fred, which nicely illustrates the inequalities of DNA inheritance.

The Sad Tale of Wanda Gruberska

So who was the mystery Gruberska cousin? Unfortunately, Cousin Jon’s family didn’t know much about the Gruberski family at all. According to family recollection, Jon’s grandmother was born Wanda Evangeline Gruberska. The family believed that she was Polish. Wanda was born circa 1913, and was left at an orphanage, either in Minnesota or Michigan, shortly after arriving in America. She was adopted out of the orphanage and her name was changed to Katherine Burke. By the time the 1930 census was enumerated, she was living with her adoptive family. Cousin Jon’s family suspected that she was not actually an orphan, but that her biological mother was unable to care for her. Armed with that information, I set out to see how Wanda fit into my family tree.

Since two of the Zarzycki women (Marianna and Aniela) had married Gruberski men (Józef and Antoni), I took a look at both of those lineages to identify the most likely candidates to be Wanda’s father. Józef and Marianna Gruberski had four children that I’d been able to discover through Polish vital records: Roman (b. 1876), Jan (b. 1877), Bolesław Leopold (b.1880), and Julia Antonina (b. 1887). Any one of the boys could have been Wanda’s father, or Julia might have been Wanda’s unwed mother.

Antoni and Aniela Gruberski had two sons, both named Bronisław, the second one (b. 1903) named after the first son Bronisław who died at the age of three. Aniela Gruberska was born in 1863, so she would have been 50 by 1913 when Wanda was born — too old to be Wanda’s mother. Similarly, her son Bronisław, and any unknown sons born after him, would be too young to be Wanda’s father. That ruled out that lineage, so the focus must be on the children of Józef and Marianna Gruberski. What was known about their descendants?

Parish records from Ilów show that Roman Gruberski married Julianna Przanowska on 21 February 1906.4 Although birth records for this parish are online and indexed at Geneteka through 1909, there are no births to this couple during that time, nor are there any births to this couple recorded in any of the indexed records on Geneteka. Parish records from Szymanów reveal that Jan Gruberski married Marianna Pindor on 23 July 1907.5 In addition to the marriage record, indexed records in Geneteka contain one birth for a child from this marriage, that of Stanisław Alfons Gruberski, who was born in Ilów on 1 May 1908.6 Finally, parish records from Rybno indicate that Bolesław Gruberski married Helena Zarzycka on 6 March 1902.7 Yes, it’s another connection between the Zarzycki and Gruberski families. Helena was Bolesław’s first cousin once removed, the youngest of the ten children of Wojciech Zarzycki and his wife, Aniela (née Tempińska). Therefore she was first cousin to Bolesław’s mother, Marianna Gruberska, even though there was 31 years’ difference in the ages of the two women. Bolesław and Helena had at least four children that I’ve been able to discover, Wacław (b. 1902), Marianna (b. 1903), Genowefa (b. 1905) and Stanisław (b. 1906), all of whom married in Nowy Dwór Mazowiecki parish between 1926-1930.

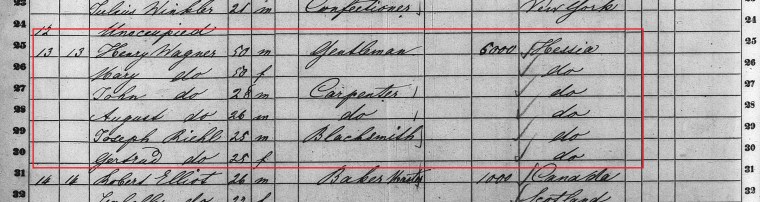

So at this point, we have some individuals who might be good candidates to be the parent(s) of Wanda Gruberska. Was there any evidence that any of them had emigrated?Yep! A little digging on Ancestry turned up a passenger manifest from 1910, which showed both Jan and Roman Gruberski coming to the U.S. in 1910 (Figure 6).

Figure 6: First page of the passenger manifest for Jan and Roman Gruberski, arriving 4 May 1910.8

On closer inspection, we see that Jan and Roman Gruberski are reported to be 31 and 34, respectively, suggesting birth years of 1879 and 1876, which is reasonably consistent with what we’d expect for our Gruberski brothers. Younger brother Jan is noted to be a laborer, while Roman was recorded as a blacksmith, consistent with the tradition of blacksmithing in the Gruberski family. Jan is reported to be from “Blędowo,” while Roman is from “Bronisławow,” which correspond to the locations of Błędów and Bronisławy, where the family is know to have lived. Jan’s nearest relative in the old country is his wife, Marya Gruberska, and Roman’s is his wife, Julia Gruberska — names that fit exactly with what is known about our Gruberski brothers. They were headed to Buffalo, New York, which is where my great-grandfather Jan Zazycki first settled when he immigrated in 1895. The manifest contains a second page which I won’t discuss in detail, since we already have more than enough information to verify that these are our Gruberski brothers and since it doesn’t add anything significant or contradict anything already supposed.

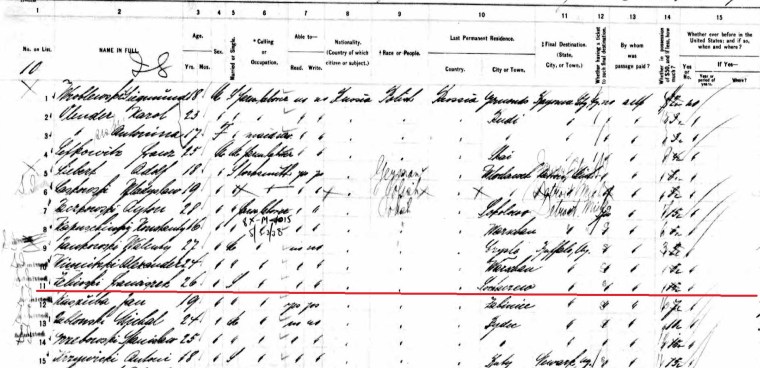

So far, so good. Two of our potential candidates for Wanda’s Gruberska’s father have made it to Buffalo. But how do we get from Buffalo to an orphanage in Michigan or Minnesota, and which one is the father? Further digging produces a second passenger manifest, this one from 1913, which shows the third brother, Bolesław Gruberski, accompanying his sister-in-law, Marianna Gruberska, to the United States, along with her two children, Stanisław and Genowefa (Figure 7).

Figure 7: First page of the passenger manifest for the Gruberski family, arriving 22 April 1913.9

Again, the ages match with what we would expect for our three known Gruberski family members, and there is a new addition to the family: little Genowefa Gruberska, age 2 years 6 months, who is the daughter of Marianna Gruberska. Genowefa’s age indicates a birth date of October 1910. All of them are reported to be from “Jeziorka,” which suggests the village of Jeziorko, about halfway in between Błędów and Bronisławy. Marianna reported her nearest relative in the old country to be her mother, Florentyna Gonsewska. The surname Gonsewska is new, perhaps indicating a second marriage, but her mother’s given name was definitely Florentyna. Marianna’s brother-in-law, Bolesław Gruberski, reports his nearest relative as his wife, Helena Gruberska. The final column gives us a critical bit of information: they were headed to St. Paul, Minnesota!

The second page of the manifest confirms that their relative in St. Paul is, in fact, Marianna’s husband, Jan Gruberski, who is also reported as the father of Stanisław and Genowefa and the brother of Bolesław (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Detail of second page of passenger manifest for Gruberski family, arriving 22 April 1913.9

The pieces are starting to fall into place, and we’re getting closer now to the orphanage in “Michigan or Minnesota” where Wanda Gruberska was adopted. The 1915 St. Paul City Directory confirms that our John Gruberski is still living there, two years after the arrival of his wife and children, and that he’s still working as a blacksmith (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Detail of R.L. Polk and Co.’s St. Paul City Directory 1915, showing John Gruberski.10

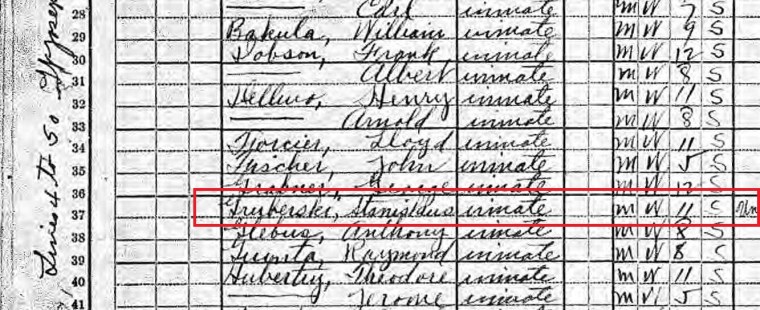

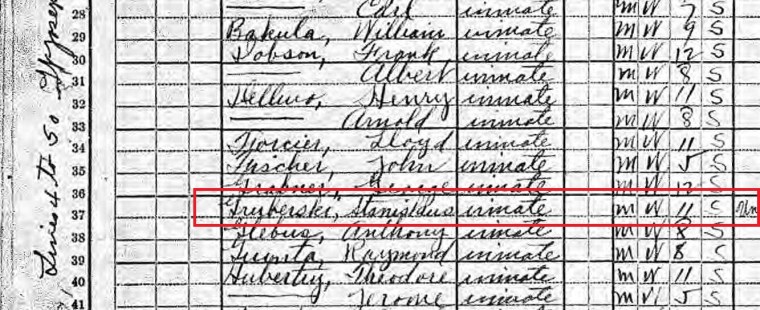

Since John’s wife Marianna arrived in April of 1913, it’s entirely possible that another daughter, Wanda, could have been born to them by January of 1914, which is reasonably consistent with Wanda’s approximate birth year of 1913. Minnesota did not conduct a state census in 1915, so the next opportunity for catching a glimpse of the whole family in documents would be the 1920 U.S. Census. However, the only member of the family who is readily found in the 1920 census is the young son, Stanisław — living in an orphanage (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Detail of the 1920 census for St. Paul (Ward 11), Minnesota, showing Stanislaus Gruberski.11

Interestingly, Stanisław is the only Gruberski child found in the census listings for that orphanage. His sister Genowefa is not there, nor is there any sign of a sister Wanda. Moreover, I have not yet been able to locate the parents, Jan and Marianna, in the 1920 census. So what happened?

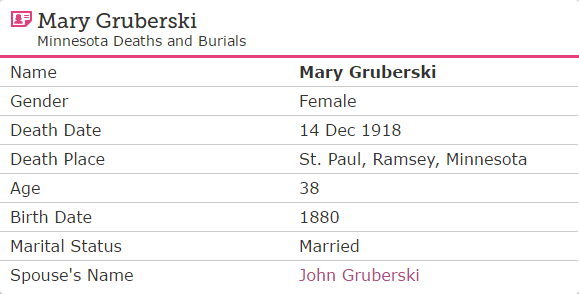

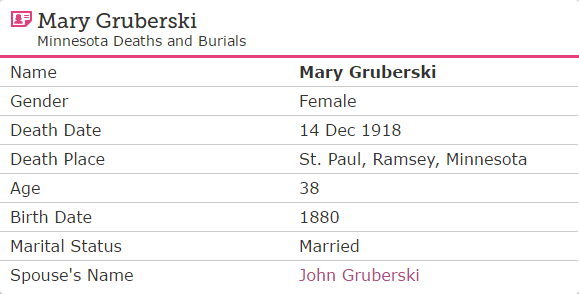

The Minnesota Deaths and Burials database gives us a clue (Figure 11), although the year of birth is significantly off from what we’ve seen in other records.

Figure 11: Entry for Mary Gruberski in the Minnesota Deaths and Burials database.12

Marianna’s year of birth suggested by records from Poland (her marriage record and Stanisław’s birth record) was 1890-1891. However, it was 1886 based on her passenger manifest, and the fact that her husband was the only Gruberski noted in the 1915 St. Paul City Directory suggests that Gruberski wasn’t a popular surname in the city at that time. Morever, the death date of 1918 is consistent with her son being placed in an orphanage by 1920. Without a family support system to help care for his children after his wife’s death, John Gruberski may have felt that he had few options.

Epilogue

Of course, this still leaves many unanswered questions, which can hopefully be resolved with more data. Although the evidence points to Wanda Gruberska being the daughter of Jan and Marianna (née Pindor) Gruberski, it should be possible to confirm that by locating a birth/baptismal record for Wanda. It would also be nice to obtain death and burial records for her mother and possibly her sister, Genowefa. St. Adalbert’s parish was an ethnic Polish parish located just one mile from the Milford Street address noted for John Gruberski in the 1915 city directory, so that would be a reasonable place to search for such records. And what became of the father, John Gruberski? He and his brother Roman seem to disappear from indexed records. However, the paper trail for his brother Bolesław suggests that he adopted the name William in the U.S. (a common choice for men named Bolesław), was still married to Helena (“Ellen”) when he registered for the draft in 1917, was a widower by 1940, and died in Chicago in 1943. Helen is not mentioned in any indexed records in the U.S. discovered to date, apart from her husband’s World War I draft registration. So her stay in the U.S. may have been brief, especially considering that all her children married in Poland.

The story had a happy ending for young Wanda, who became Katherine Burke. Cousin Jon’s family reports that she married, raised her family, loved to cook, and was beloved by her children and grandchildren until her death in 1991. But what of her brother, Stanisław Gruberski, last seen as an 11-year-old boy in the orphanage in 1920? He, too, disappears from the records, but like his sister Wanda, his name might have been changed upon adoption. We may never know if there are any cousins stemming from his line — unless, of course, they wonder about their origins and turn to DNA testing for answers.

Sources:

1 Roman Catholic Church, St. Bartholomew Parish (Rybno, Sochaczew, Mazowieckie, Poland), Księga ślubów 1868-1886, 1874, #15, marriage record for Józef Gruberski and Maryanna Zarzycka. “#15, Bronisławy. It happened in the village of Rybno on the thirteenth/twenty-fifth day of October in the year one thousand eight hundred seventy-four at four o’clock in the afternoon. We declare that, in the presence of witnesses Maciej Bartoszewski, age thirty-eight, and Wawrzyniec Pytkowski, age forty, both farmers residing in the village of Bronisławy, that on this day was contracted a religious marital union between Józef Gruberski, widower after the death on the tenth/twenty-second day of October in the year one thousand eight hundred seventy in the village of Błędów of his wife, Anna née Trojanowska; blacksmith residing in the village of Błędów, born in the village of Ożarów, age forty, son of the late Mateusz and Nepomucena née Banowska, the spouses Gruberski; and Maryanna Zarzycka, single, born in the village of Bronisławy, age twenty-four, daughter of Ignacy and Antonina née Naciążek, the spouses Zarzycki, farmers residing in the village of Bronisławy; in that same village of Bronisławy residing with her parents. The marriage was preceded by three announcements on the twenty-second day of September/fourth day of October, the twenty-ninth day of September/eleventh day of October, and the sixth/eighteenth day of October of the current year in Rybno and in the parish church in Łowicz. The newlyweds stated that they had no prenuptial agreement between them. The marriage ceremony was performed by Fr. Józef Bijakowski (?). This Act to the declarant and witnesses was read aloud but signed only by us because they are unable to write. [Signed] Fr. Józef Bijakowski, pastor of Rybno performing the duties of Civil Registrar.”

2 Akta stanu cywilnego parafii rzymskokatolickiej w Rybnie, Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne, Metryki.genealodzy.pl: Projekt indeksacjia metryk parafialnych (http://metryki.genealodzy.pl/), 1890, Marriages, #1, accessed on 26 January 2017. “#1. This happened in the village of Rybno on the seventh/nineteenth day of January in the year one thousand eight hundred ninety at three o’clock in the afternoon. We declare that, in the presence of witnesses Mateusz Kania, farmer residing in the village of Bronislawy, age thirty-seven (?), and Aleksander Lesiak, organist residing in the village of Rybno, age thirty-two; on this day was contracted a religious marriage between Antoni Gruberski, blacksmith, soldier on leave, single, born in the village of Bledów, in the district of Lowicz, son of Józef and the late Anna née Trojanowska, the spouses Gruberski, residing in the village of Bronislawy, having twenty-six years of age; and Aniela Zarzycka, single, residing and born in the village of Bronislawy, living with her parents, daughter of Ignacy and Antonina née Naciazek, the spouses Zarzycki, having twenty-four years of age. The marriage was preceded by three readings of the banns in the local parish church on the twenty-fourth and thirty-first days of December in the year one thousand eight hundred eighty nine [corresponding to the fifth and twelvth days of January and the] seventh/nineteenth days of January of the current year, after which no impediments were found. The newlyweds stated that they had no premarital agreement between them. The religious ceremony of marriage was performed by Fr. Grigori Gruzinski (?), local administrator of the parish of Rybno. This document was read aloud to the declarants and witnesses and was signed by Us and by the second witness due to the illiteracy of the other witnesses. [Signed] Fr. Grigori Gruzinski, Administrator of the parish and keeper of vital records [signed] Aleksander Lesiak”

3 Książka Rzemieślnicza Czeladnika Kunsztu Kowalskiego Jana Zarzyckiego, Worker’s identification book for Jan Zarzycki, 29 August 1886, privately held by John D. Zazycki, Milford, Ohio, 2000.

4 Akta stanu cywilnego parafii rzymskokatolickiej w Ilowie, Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne, Metryki.genealodzy.pl: Projekt indeksacji metryk parafialnych (http://metryki.genealodzy.pl/), 1906, Marriages, #15, record for Roman Gruberski and Julianna Przanowska, accessed on 26 January 2017.

5 Akta stanu cywilnego parafii rzymskokatolickiej w Szymanowie, Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne, Metryki.genealodzy.pl: Projekt indeksacji metryk parafialnych (http://metryki.genealodzy.pl/), 1907, marriages, #25, record for Jan Gruberski and Maryanna Pindor, accessed on 26 January 2017.

6 Akta stanu cywilnego parafii rzymskokatolickiej w Ilowie, Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne, Metryki.genealodzy.pl: Projekt indeksacji metryk parafialnych (http://metryki.genealodzy.pl/), 1908, births, #52, record for Stanislaw Alfons Gruberski, accessed on 26 January 2017.

7 Akta stanu cywilnego parafii rzymskokatolickiej w Rybnie, Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne, Metryki.genealodzy.pl: Projekt indeksacjia metryk parafialnych (http://metryki.genealodzy.pl/), Ksiega slubów 1888-1908, 1902, #6, marriage record for Boleslaw Leopold Gruberski and Helena Zarzycka, accessed on 26 January 2017.

8 New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 (image), Jan Gruberski and Roman Gruberski, S.S. Bremen, 4 May 1910, http://ancestry.com, subscription database, accessed January 2017.

9 New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 (image), Marianna, Stanisław, Genowefa, and Bolesław Gruberski, S.S. President Lincoln, 22 April 1913, http://ancestry.com, subscription database, accessed January 2017.

10 U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 (images), John Gruberski, St. Paul, Minnesota, 1915, http://ancestry.com, subscription database, accessed January 2017.

11 1920 U.S. Census (population schedule), St. Paul, Ramsey, Minnesota, ED 140, sheet 4A, Stanislaus Gruberski, St. Joseph’s German Catholic Orphan Society (institution), http://familysearch.org, accessed January 2017.

12 Minnesota Deaths and Burials, 1835-1990, index-only database, https://familysearch.org, record for Mary Gruberski, 14 Dec 1918; citing St. Paul, Ramsey, Minnesota, reference 1407; FHL microfilm 2,218,025, accessed on 27 January 2017.

© Julie Roberts Szczepankiewicz 2017

Anna (née Meier) Boehringer, John Boehringer, and Joseph Zielinski, June 1969, Grand Island, New York.

Anna (née Meier) Boehringer, John Boehringer, and Joseph Zielinski, June 1969, Grand Island, New York.

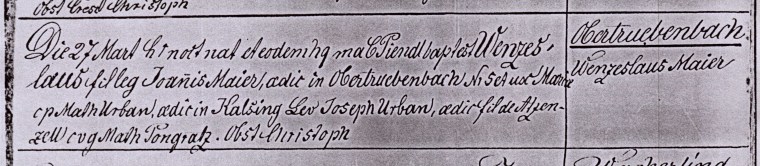

According to the Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007, he was born 27 March 1871 in Roding, Federal Republic of Germany.1 He came to the U.S. in 1890, on board the S.S. Fulda, which departed from Bremen and Southhampton and arrived in the port of New York on 8 August.2 The passenger manifest states that his last residence was “Obertrubenbach” (Figures 1a and b).

According to the Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007, he was born 27 March 1871 in Roding, Federal Republic of Germany.1 He came to the U.S. in 1890, on board the S.S. Fulda, which departed from Bremen and Southhampton and arrived in the port of New York on 8 August.2 The passenger manifest states that his last residence was “Obertrubenbach” (Figures 1a and b).

, 1904, #15, marriage record for Leonard Zarzycki and Maryanna Majewska, accessed on 31 October 2015. http://metryki.genealodzy.pl/metryka.php?ar=2&zs=1279d&sy=250&kt=17&plik=15-16.jpg)