Family stories are always the starting point for genealogy research. Beginners are typically instructed to start with themselves and work backwards, interviewing older family members or generational peers to discover what they remember, or remember hearing, about past generations. Often it feels like a game of “telephone” played out over many decades. You may remember “telephone” as that game in which a number of players stand in a circle, and a complicated phrase is whispered from one person to the next. Repetition is not allowed, so although each person does his best to listen carefully, the phrase becomes distorted, often comically, as it is passed around. Finally the result is whispered to the person who began the game, who announces what the original phrase actually was, and everyone gets a good laugh. As family historians, our job is to sift out the wheat from the chaff, using our ancestors’ paper trail to document what we can from the family stories, but keeping in mind that not everything we were told is going to be verifiable.

I became interested in my family history soon after I was married in 1991. My husband and I were incredibly fortunate to have six living grandparents at that time, as well as plenty of their siblings still living. As I’ve tried to document all the many bits of information I gathered from them, one truth in particular has emerged: if an older relative remembers a specific name, it’s safe to say that the person is connected to the family in some way, even if it’s not in the way that he or she remembers. Remembered names aren’t just pulled out of thin air.

As one example of this, I interviewed Uncle Mike Stevenson (Szczepankiewicz) about the Szczepankiewicz family history. Uncle Mike was the youngest brother of my husband’s grandfather, Stephen Szczepankiewicz. Although he knew a great deal about his father from his mother’s stories, Uncle Mike had never met him: he died on 14 February 1926,1 and Uncle Mike was born 3 months later, on 23 May 1926.2 Nonetheless, Uncle Mike proved to be a reliable source. He told me that his father, Michael Szczepankiewicz, had never naturalized. This assertion is validated by the 1925 New York State census, in which Michael Szczepankiewicz is listed as an alien (Figure 1):3

Figure 1: Extract of 1925 New York State census showing Michael Szczepankiewicz and family.3

This extract shows that 49-year-old Michael Szczepankiewicz was born in Poland, had been living in the U.S. for 20 years, was an alien (“al”) at the time of the census, and was employed in “building labor.” Since Michael died in 1926, and the naturalization process took longer than a year, it would not have been possible for him to naturalize prior to his death. Uncle Mike also mentioned that his father was a stone mason who helped to build Transfiguration Church in Buffalo. Although I have yet to document this directly (maybe payroll records exist in the archive of the diocese of Buffalo dating back to the construction of Transfiguration Church?), the fact that Michael was a construction laborer is consistent with that claim.

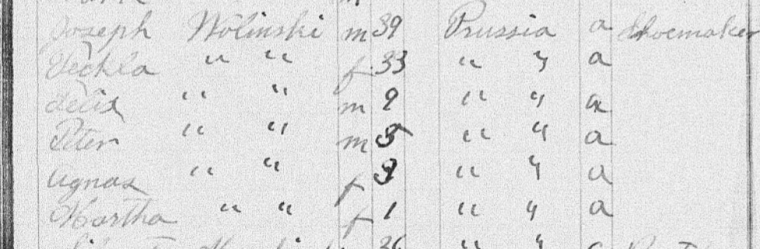

When I asked Uncle Mike about the family of his mother, Agnes (née Wolińska) Szczepankiewicz, he told me that Agnes’s mother was named Apolonia Bogacka. Unfortunately, this didn’t pan out. Records showed that Agnes’s mother’s name was Tekla, as shown by the 1892 census for New York State (Figure 2): 4

Figure 2: Extract from 1892 census of New York State showing the family of Joseph Wolinski, including wife “Teckla” (sic).4

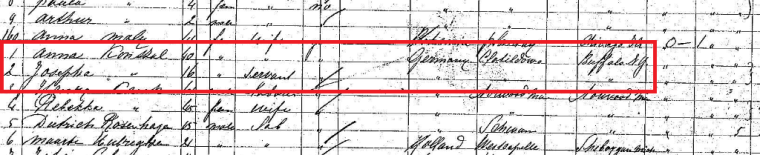

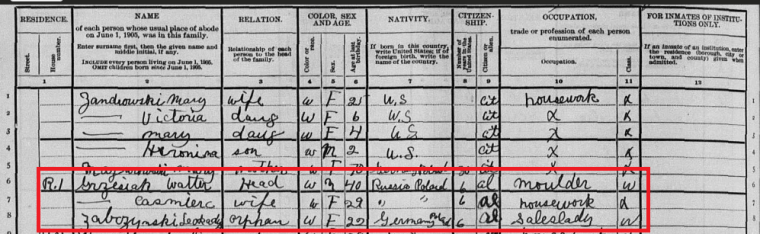

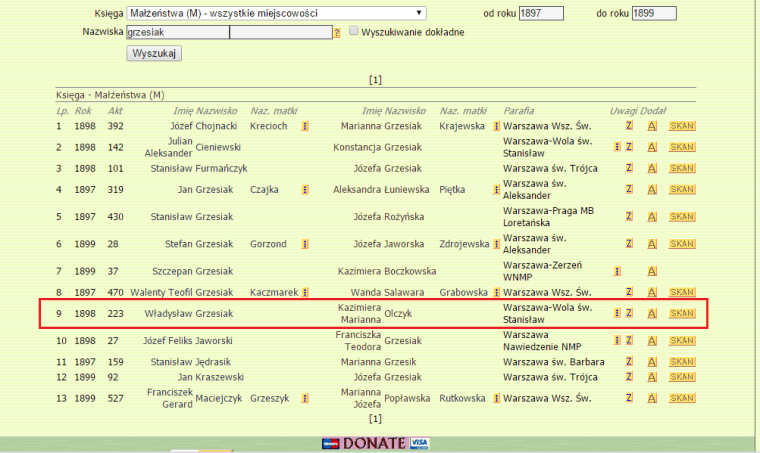

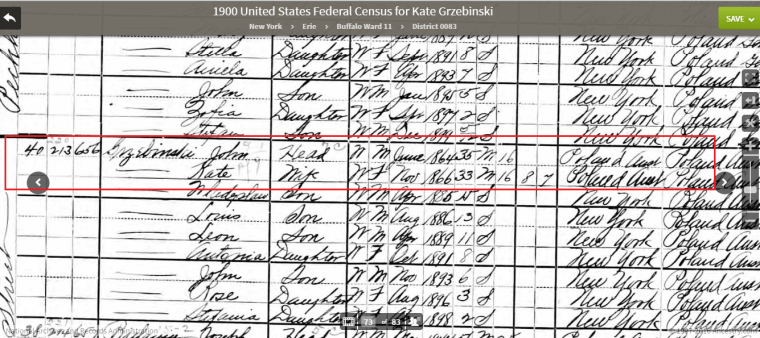

So where did the name “Apolonia Bogacka” come from? The answer was found in the 1900 census (Figure 3).5 Living with Joseph Wolinski’s family is his mother-in-law, “Paline” Bogacka. The name “Pauline” was commonly used by women named Apolonia in the U.S. as a more American-sounding equivalent.

Figure 3: Extract from the 1900 U.S. Federal census showing the family of Joseph Wolinski, including mother-in-law “Paline” (sic) Bogacka.5

So it turns out that Uncle Mike’s great-grandmother had also emigrated, and he was confusing her name with the name of his grandmother!

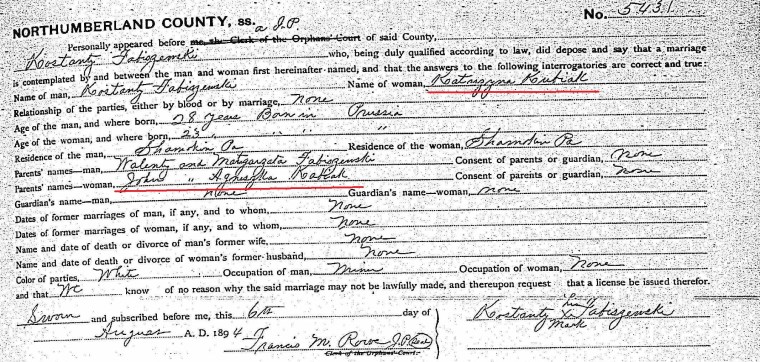

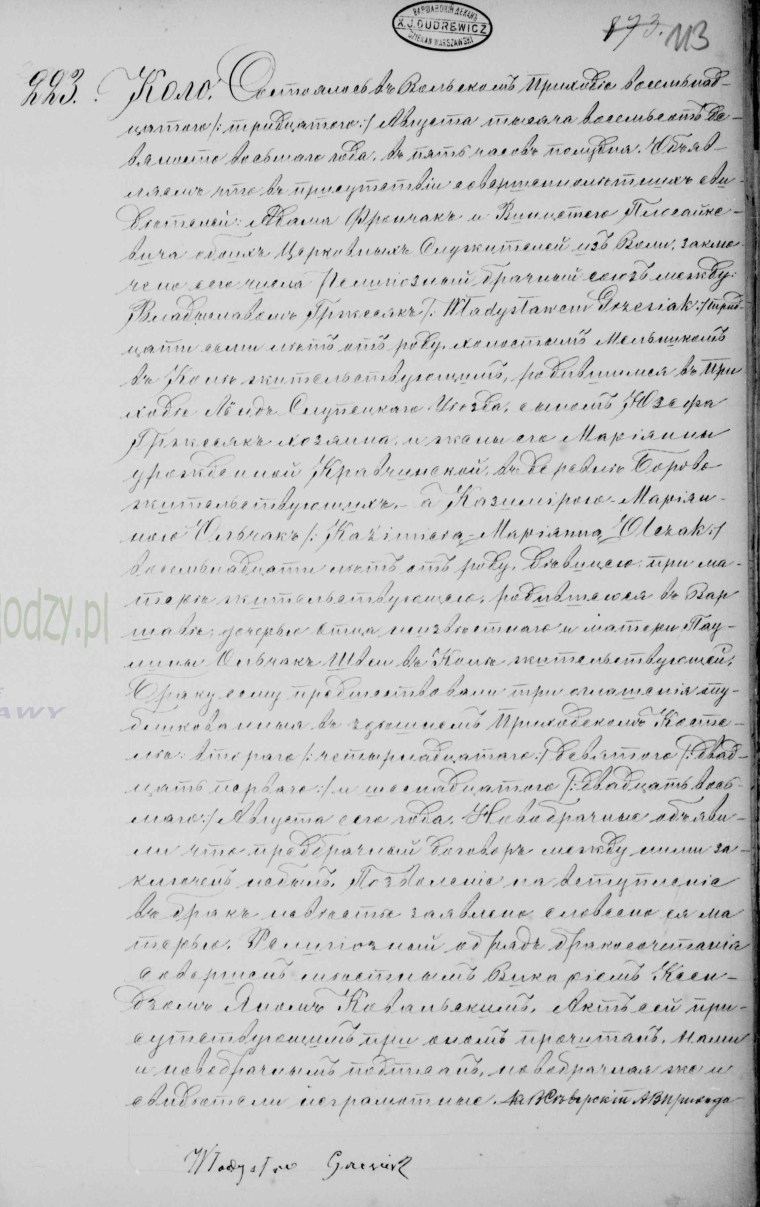

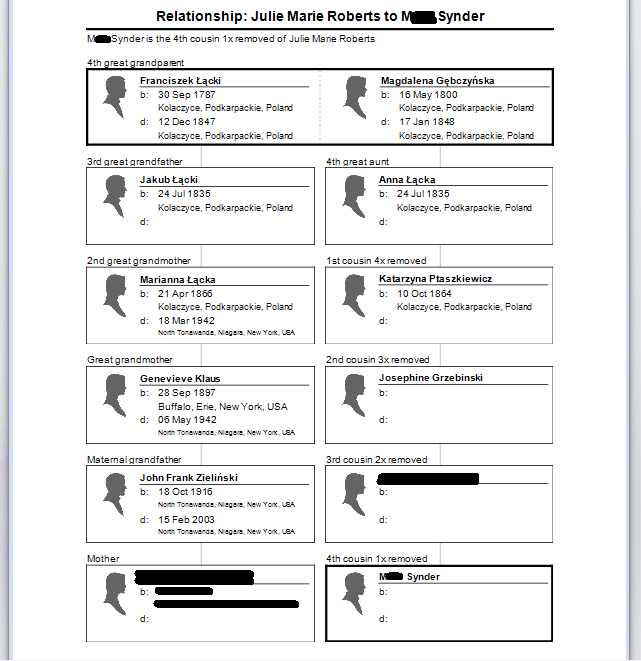

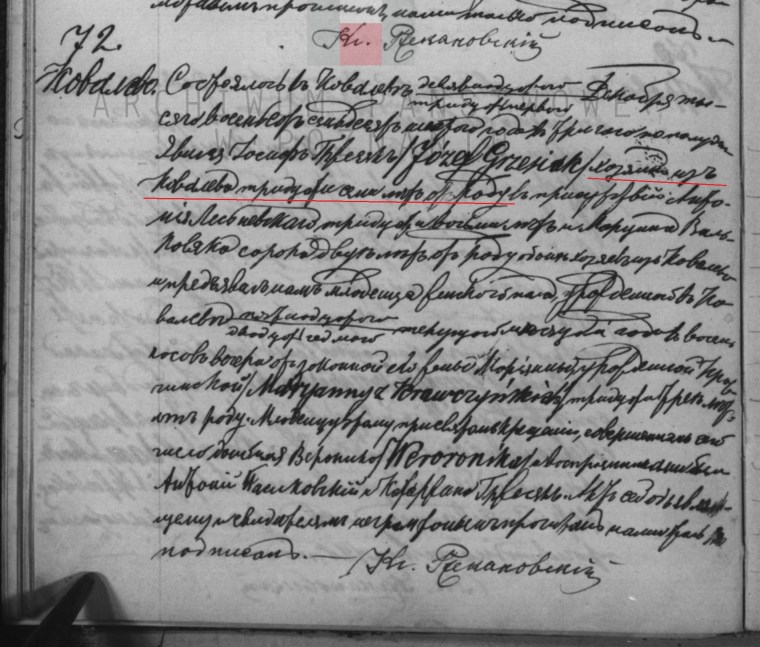

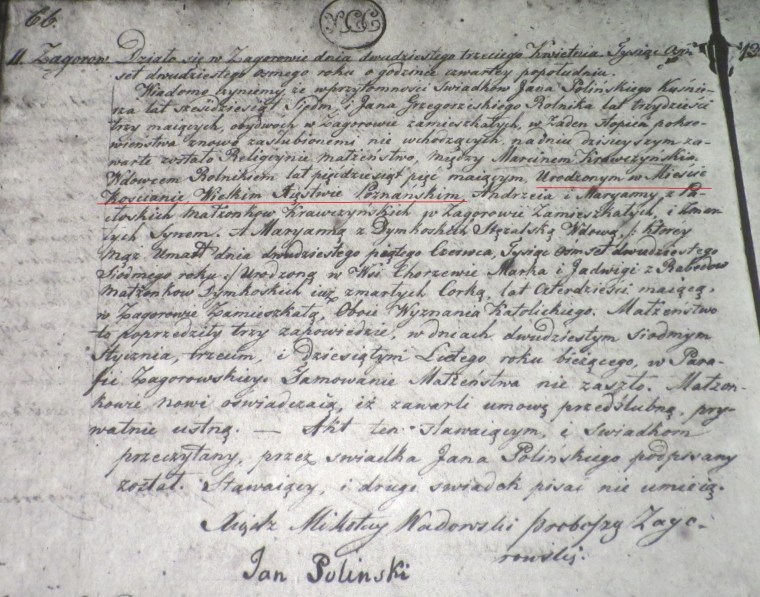

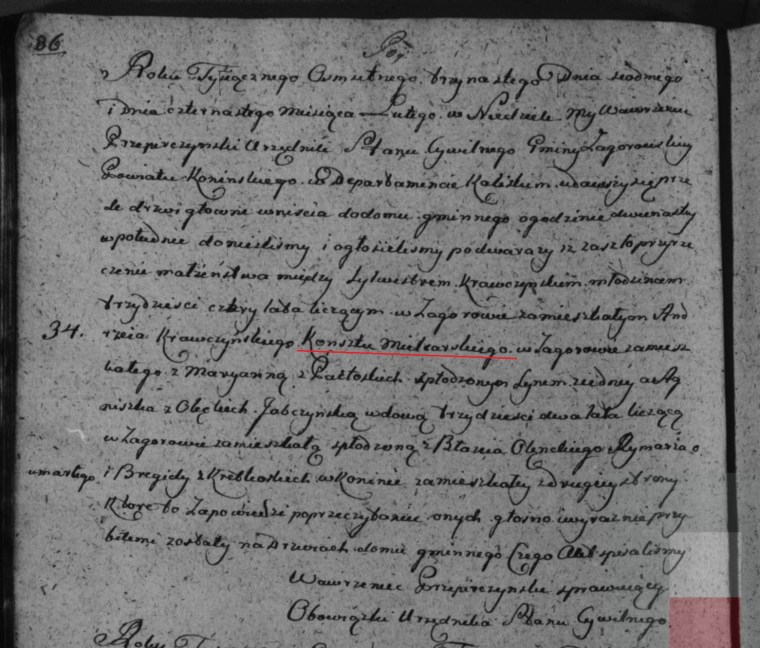

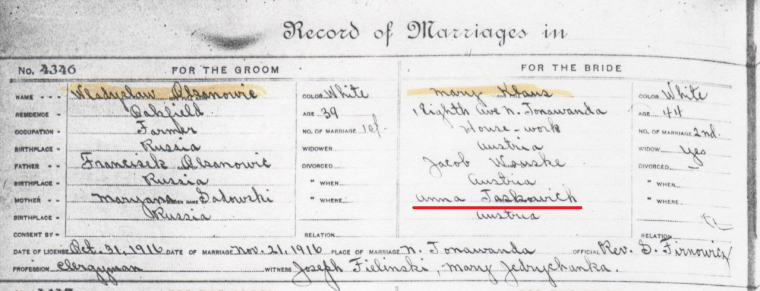

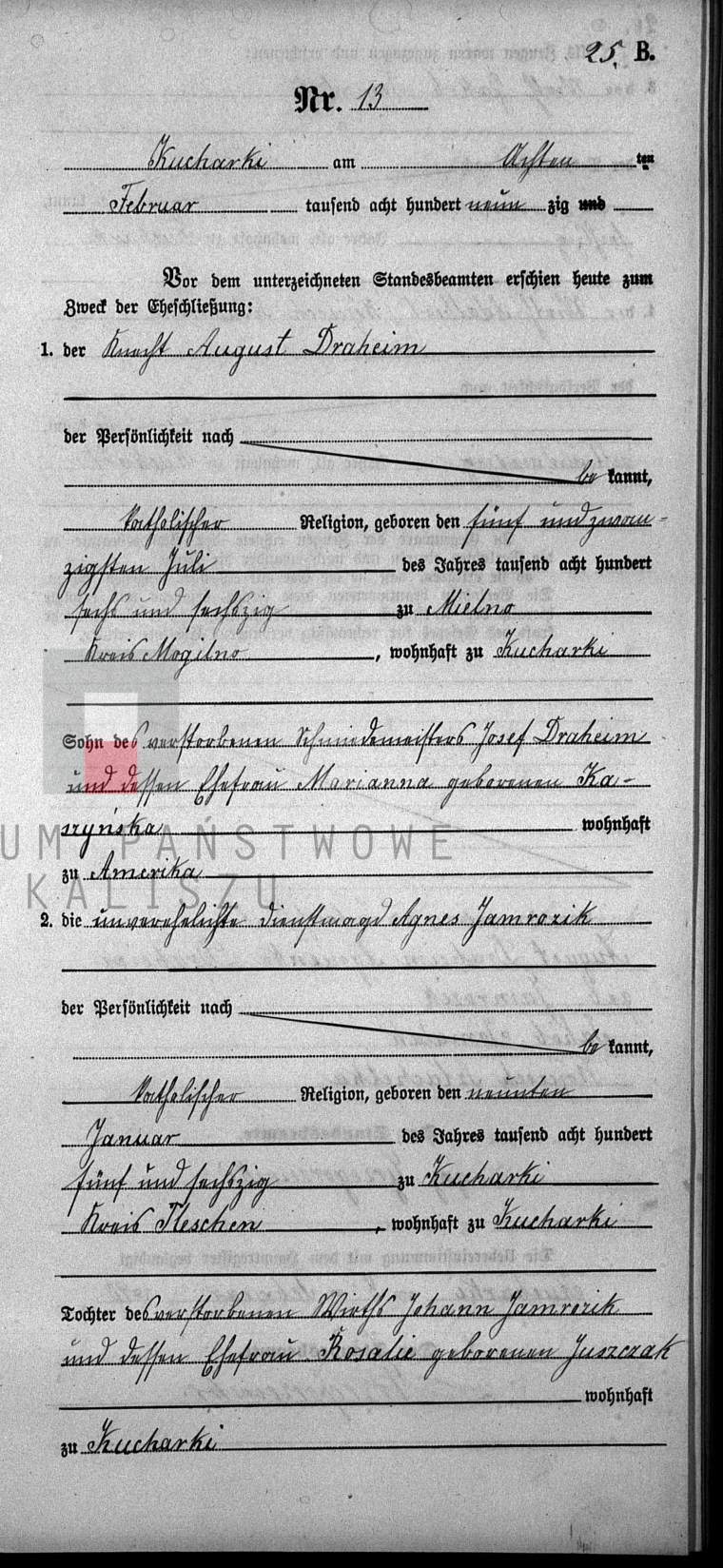

As another example, my grandfather’s first cousin, Jul Ziomek, told me in a 1992 interview that the mother of her grandmother, Mary (née Łącka) Klaus, was named Janina Unicka. Jul was a very reliable source in other matters, but in this case, her memory did not serve her well. The civil record for Mary Klaus’s second marriage, to Władysław Olszanowicz, tells us that her mother’s name was (phonetically) Anna “Taskavich” (Figure 4).6

Figure 4: Civil marriage record from North Tonawanda, New York, for Mary Klaus and Władysław Olsanowic (sic).6

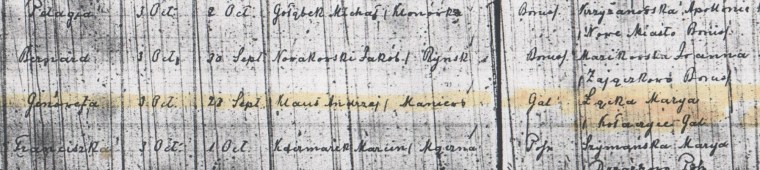

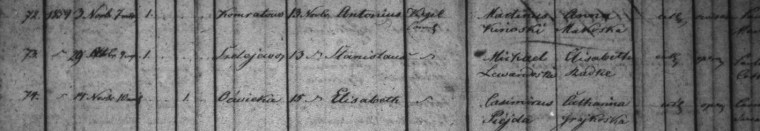

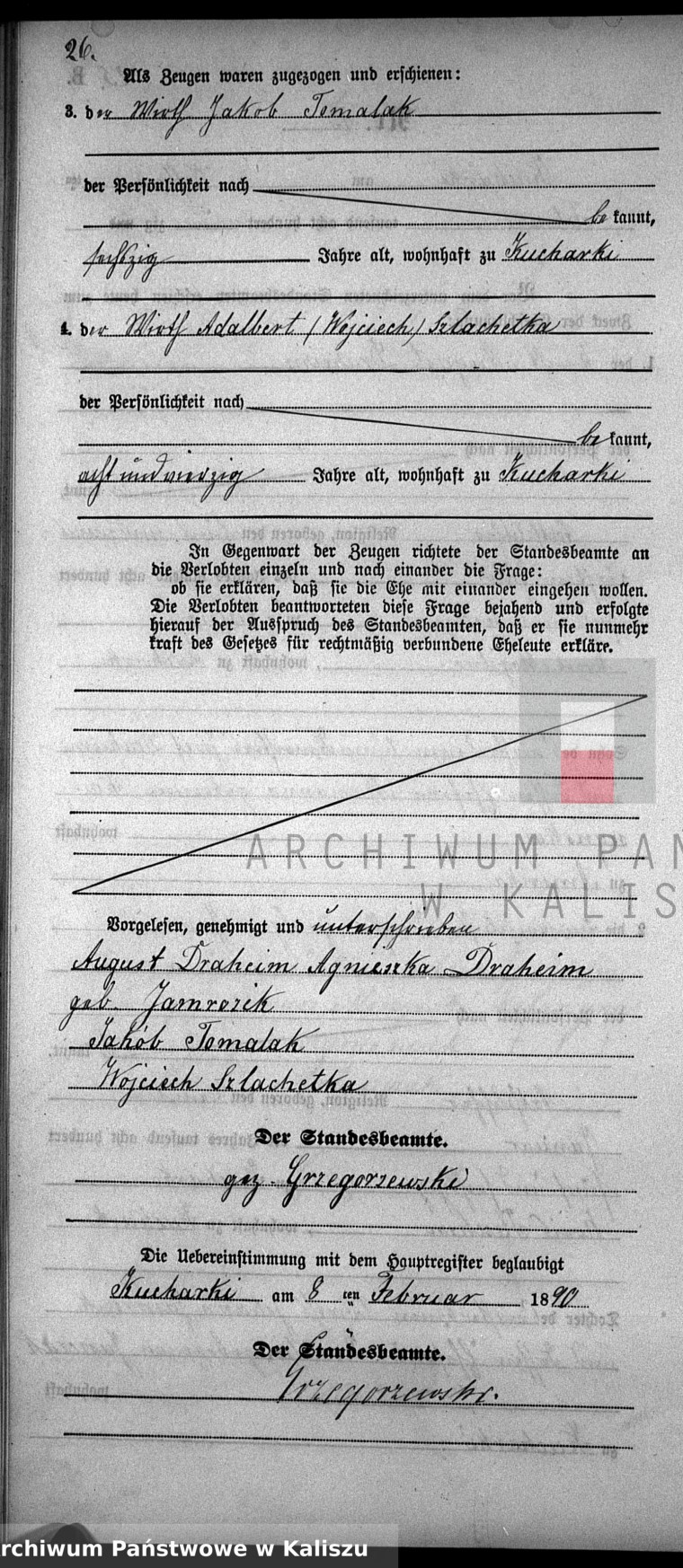

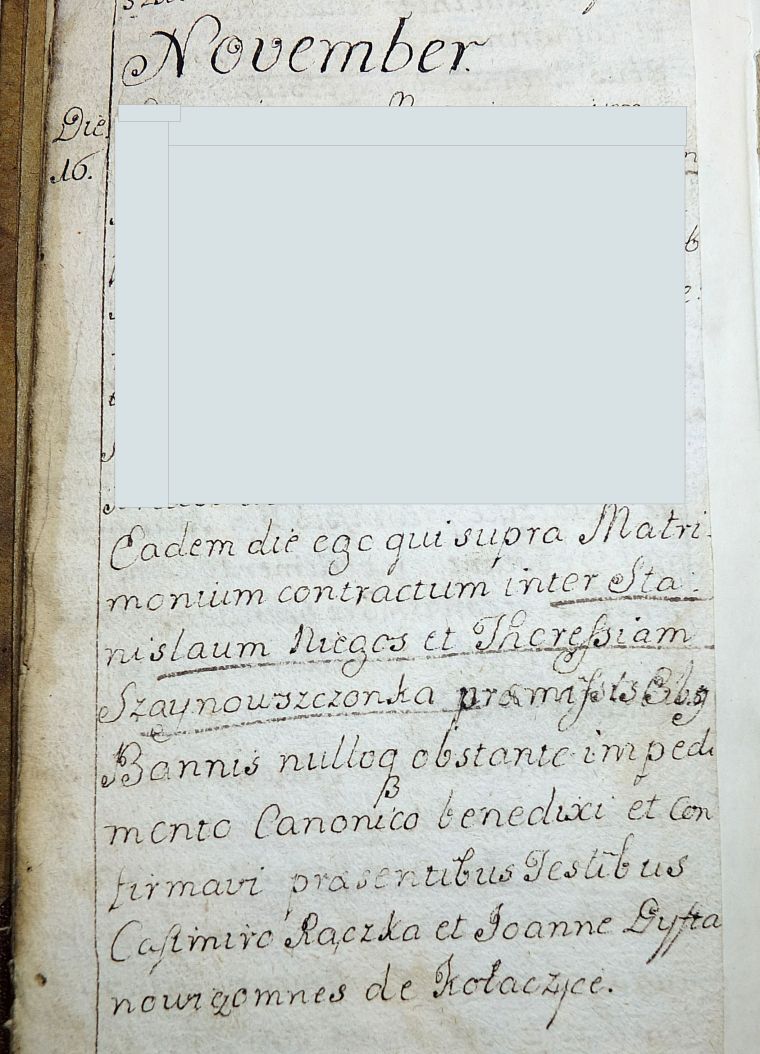

The correct spelling of Mary’s mother’s name in Polish is found on Mary’s baptismal record from her home village of Kołaczyce — she was Anna Ptaszkiewicz (Figure 5).7

Figure 5: Baptismal record from Kołaczyce, Austrian Poland for Marianna Łącka.7

The section of the record in the red box pertains to the mother of the child and reads, “Anna filia Francisci Ptaszkiewicz ac Salomea nata Francisco Sasakiewicz.” For those who might be unfamiliar with Latin, this translates as “Anna, daughter of Franciszek Ptaszkiewicz and Salomea, daughter of Franciszek Sasakiewicz.”

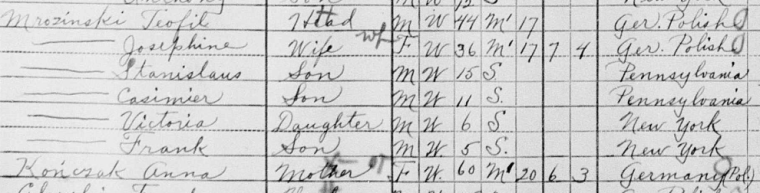

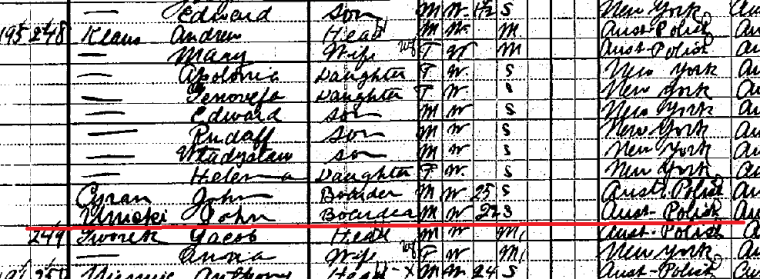

Believe it or not, it’s quite reasonable, based on Polish phonetics, that an English speaker might come up with a spelling of “Taskevich”for “Ptaszkiewicz.” But no matter how you slice it, this is pretty far off from “Janina Unicka.” So where did Jul come up with that name? The 1910 census gives us a clue (Figure 6):8

Figure 6: Andrew Klaus family in the 1910 U.S. Federal census.8

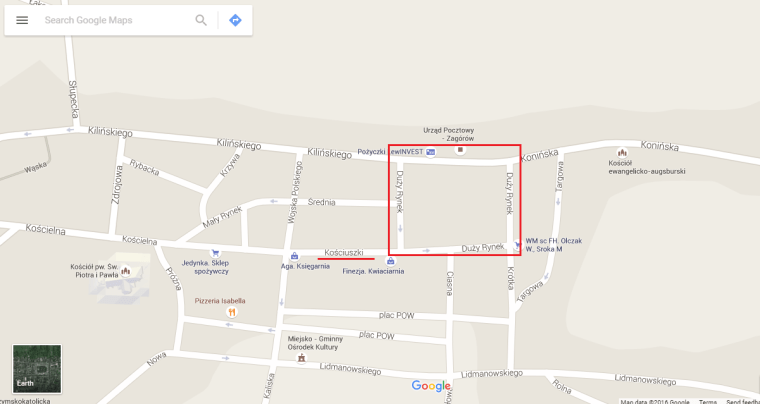

Living with the family of Mary Klaus, there is a boarder named John Unicki. At this point I have traced Mary Klaus’s family back in Poland for another 3-4 generations, which is as far back as existing vital records go, and I’ve seen no evidence of the Unicki surname anywhere in the extended family tree. I’ve concluded that cousin Jul’s memory was inaccurate on this point. It must have been dim memories of this boarder, Jan Unicki, living with her grandparents that caused her to associate the name “Janina Unicka” with her grandmother’s family.

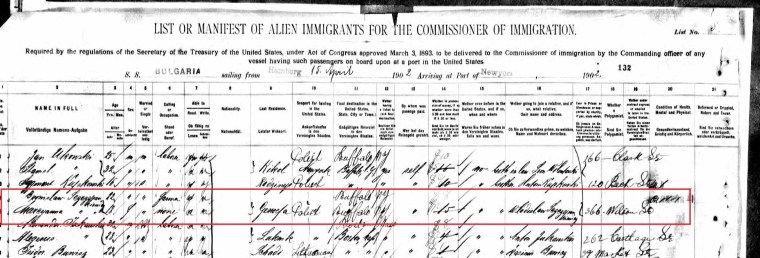

As one final example, my husband’s grandfather, Stephen Szczepankiewicz, told me that his father, Michael Szczepankiewicz, immigrated from Russian Poland to Buffalo, New York, along with four brothers and no sisters. He recalled the names of his father’s brothers as Bernard, Felix, Alexander and Joseph. It turns out that he was partially correct. Further research indicates that his father did indeed have brothers who also emigrated from Poland to Buffalo who were named Bernard (Anglicized from Bronisław), Alexander, and Joseph. What Grandpa didn’t know was that there were two more brothers who emigrated, Adam and Walter (also known as “Wadsworth” — both names are Anglicized versions of his Polish name, Władysław), as well as a sister, Marcjanna, who emigrated to Buffalo along with Bronisław and then disappears from records there (Figure 7):9

Figure 7: Passenger manifest for Marcyanna and Bronisław Szczepankiewicz, arriving in the port of New York on 3 May 1902.9

Try as I might, I could not document a brother named Felix/Feliks Szczepankiewicz, or find one with a name that was even close to that. Why would Grandpa remember an Uncle Felix if there never was one? Well, it turns out that there was an Uncle Felix, but it was on his mother’s side, not his father’s side. Grandpa Steve’s mother was Agnes/Agnieszka Wolińska. If we take a closer look at that 1892 census for the Woliński family shown in Figure 2 and the 1900 census shown in Figure 3, the oldest child in the family is Feliks. So it seems likely that Grandpa was just mixing up which side of the family Uncle Feliks was from.

As is evident from these examples, family stories work best when used as a starting point for genealogy research, but we can’t let our research end there. Time can play tricks with people’s memories, so it’s important to attempt to document everything we’ve been told. If conflicts exist between the story and the evidence, consider how these might be reconciled. As you document each story, you’ll begin to get a sense of the reliabilty of each relative’s memory. If you have any particularly wild stories that you’ve been able to document, please let me know in the comments — I’d love to hear about them!

Sources:

1 Buffalo, Erie, New York, Death Certificates,1926, certificate #1029, record for Michael Sczepankiewicz (sic).

2 “United States Social Security Death Index,” database, FamilySearch(https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VMDV-RJ7 : 20 May 2014), Michael A Stevenson, 28 Apr 2011; citing U.S. Social Security Administration, Death Master File, database (Alexandria, Virginia: National Technical Information Service, ongoing), accessed on 8 November 2016.

3 Ancestry.com, New York, State Census, 1925 (Provo, UT, USA, Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012), http://www.ancestry.com, Record for Stepahn Szczepankiewicz, accessed on 8 November 2016.

4 Ancestry.com, New York, State Census, 1892 (Provo, UT, USA, Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012), http://www.ancestry.com, Record for Joseph Wolinski household, accessed on 8 November 2016.

5 Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census (Provo, UT, USA, Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2004), http://www.ancestry.com, Year: 1900; Census Place: Buffalo Ward 9, Erie, New York; Roll: T623_1026; Page: 6A; Enumeration District: 69, record for Joseph Wolinski household, accessed on 8 November 2016.

6 “New York, County Marriages, 1847-1848; 1908-1936″, database, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, Family Search, (https://familysearch.org), Wladyslaw Olsanowic and Mary Klaus, 21 Nov 1916; citing county clerks office, , New York, United States; FHL microfilm 897,558. accessed on 8 November 2016.

7 Roman Catholic Church, St. Anna’s Parish (Kołaczyce, Jasło, Podkarpackie, Poland), “Urodzenia, 1826-1889”, Stare Kopie, 1866, #20, Record for Marianna Łącka.

8 Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census (Provo, UT, USA, Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006), http://www.ancestry.com, Year: 1910; Census Place: North Tonawanda Ward 3, Niagara, New York; Roll: T624_1049; Page: 16B; Enumeration District: 0126; FHL microfilm: 1375062, record for Andrew Klaus, accessed on 8 November 2016.

9 Ancestry.com, New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 (Provo, UT, USA, Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010), http://www.ancestry.com, Year: 1902; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957; Microfilm Roll: Roll 0272; Line: 5; Page Number: 132, record for Marcyanna Sczezyoankiemg, accessed on 8 November 2016.

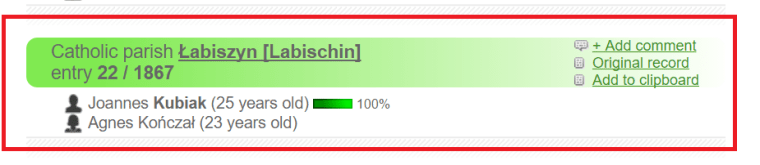

He wondered if I might have any insight into who the people were. I was excited to see the photo, and believed I could tell him exactly who these people were because Grandma Barth showed me this same photo before she died, and filled me in. I thought this photo would be a nice subject for a blog post, so I started to gather a bit of background documentation to provide some insight into the lives of the people shown here. In the process, I’ve discovered that things aren’t really what they seemed, and maybe — just maybe — Grandma might have been wrong about a thing or two.

He wondered if I might have any insight into who the people were. I was excited to see the photo, and believed I could tell him exactly who these people were because Grandma Barth showed me this same photo before she died, and filled me in. I thought this photo would be a nice subject for a blog post, so I started to gather a bit of background documentation to provide some insight into the lives of the people shown here. In the process, I’ve discovered that things aren’t really what they seemed, and maybe — just maybe — Grandma might have been wrong about a thing or two.