A few days ago, I wrote to the Konin branch of the Polish State Archive of Poznań to request a search for death records for Pelagia and Konstancja Grzesiak, who were two sisters of my great-grandmother. This is pretty routine for me now, but when I first began researching Polish vital records, I was intimidated by the thought of writing to an archive in Poland. I worried that it would be prohibitively expensive, and I worried about translating their correspondence in an era before Facebook groups and Google Translate. However, writing to the archives is pretty straightforward, and should be a standard research strategy for anyone researching Polish ancestors. In this post, I’ll walk you through the process of writing to an archive to request records for your family in Poland.

Why Write to an Archive?

Although it’s true that more and more vital records from Poland are coming online every day, thanks to the efforts of both the state archives and the various Polish genealogical societies, there are still plenty of records that are not available online or on microfilm from the LDS. Some of these records can be found in the diocesan archives, some are in the state archives, and some may still be at the parishes themselves. You might need to rely on multiple sources to find records in the range of years you need to thoroughly document your family history.

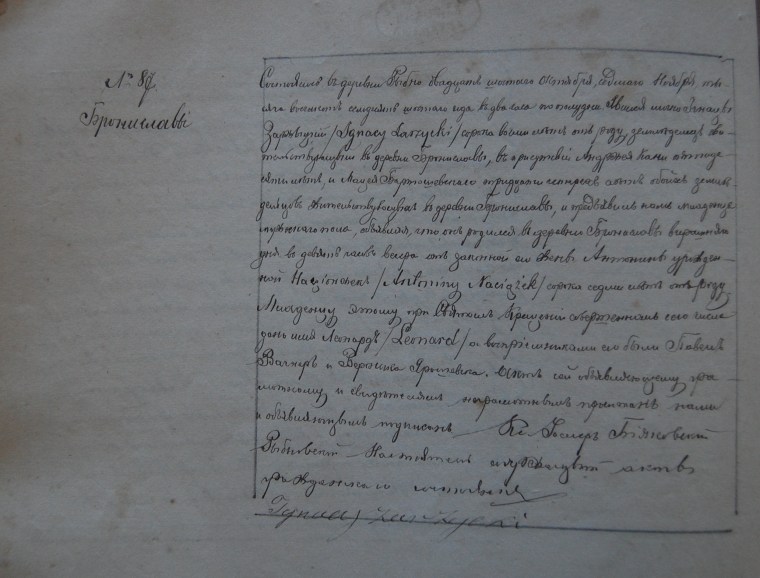

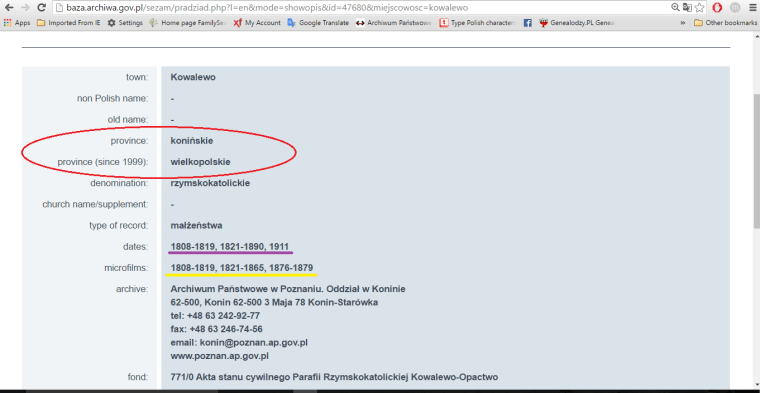

As an example, for my Grzesiak’s ancestral parish in Kowalewo-Opactwo, the LDS has both church and civil records available on microfilm. However, upon closer examination, we see that the civil records only go from 1808-1865, then there’s a two-year gap, after which coverage extends from 1868-1879. The church records might be helpful in tracing some of my collateral lines forward in time, since they begin in 1916, but they aren’t useful for finding ancestors. Those records go all the way up to 1979 (with gaps), which is interesting, given that Polish privacy laws typically restrict access to such recent records.

Microfilm is great, but online access is even better, and in the years since I began researching this family, records for Kowalewo have come online for those same years from 1808-1879, including that same gap from 1866-1867. One might conclude that the records from 1866-1867 were destroyed, since they don’t appear in either the online collection from the Archiwum Państwowe w Poznaniu Oddział w Koninie (State Archive of Poznań Branch in Konin) or on the LDS microfilm. However, that’s not the case, those records DO exist. How do we know this?

Baza PRADZIAD: The Vital Records Database for the Polish State Archives

Baza PRADZIAD can be searched quickly, easily, and in English to see what vital records are held by the various state archives for any given parish or civil registry office. Note that you must know the parish or civil registry office for your village of interest. If I search for records for Wola Koszutska, which is a village belonging to the parish in Kowalewo, I won’t get any hits. But I can find records for ancestors born in Wola Koszutska by knowing that their vital events would have been recorded at the parish in Kowalewo. Although Polish diacritics aren’t supposed to be important when searching this site, I’ve had it happen on occasion that a search without diacritics comes up empty, but redoing the search with diacritics gives good results. Maybe that was due to cybergremlins, or maybe there are bugs that only affect certain parishes, but it’s something to consider if nothing turns up the first time you search. There are ways to set up your keyboard to allow for Polish diacritics, but if you haven’t done that or don’t know how, there’s always this site which works in a pinch so you can copy and paste your proper Polish text into the search box.

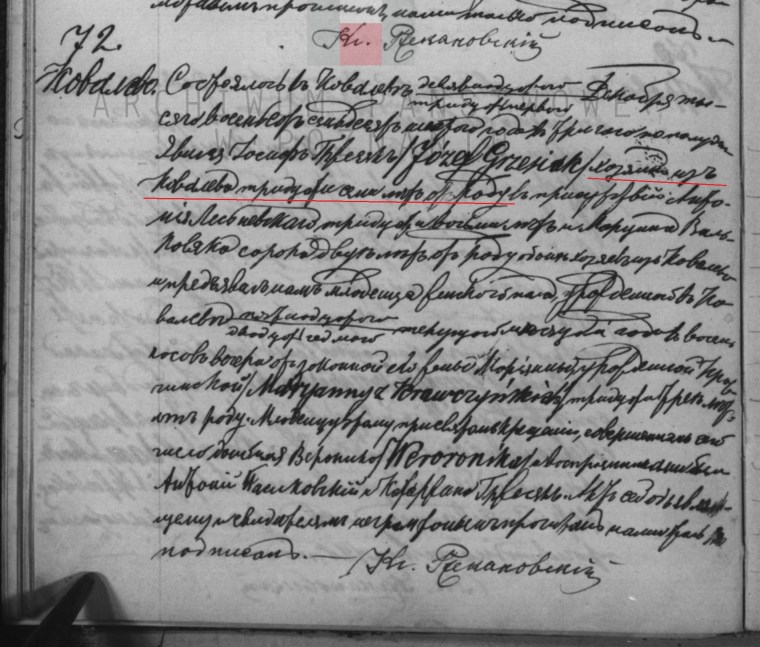

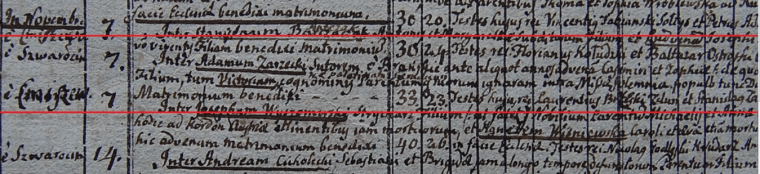

Now, let’s take a look at what comes up in Baza PRADZIAD for Kowalewo (Figure 1):

Figure 1: Baza PRADZIAD Search Screen

Figure 1 shows the search screen, and as you’ll see, I got results only by entering the town name. There are options for restricting the search by entering the “commune” (i.e. gmina), province, religion, or type of event you’re looking for, but you really don’t need all that, and sometimes simple is best.

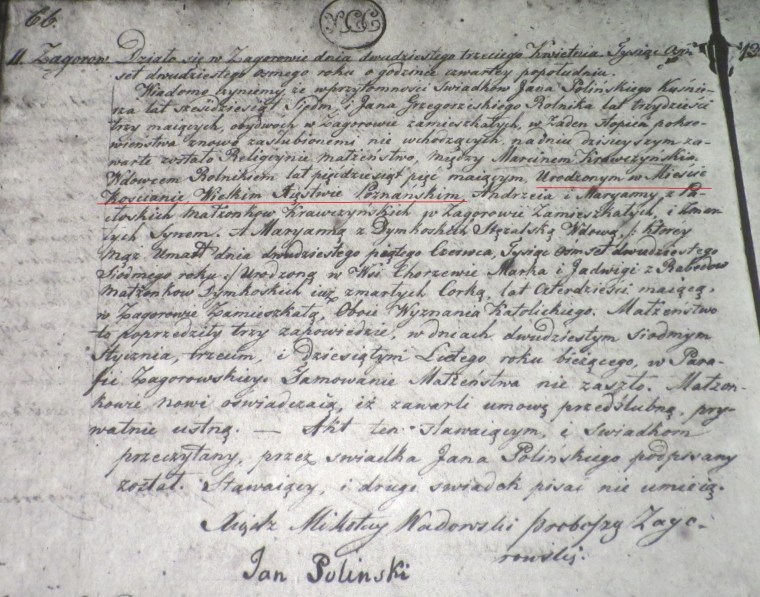

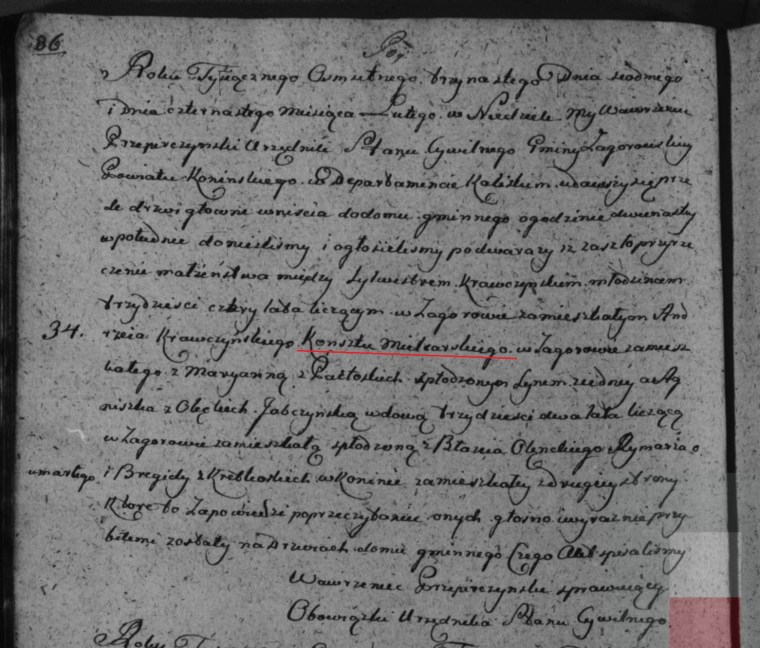

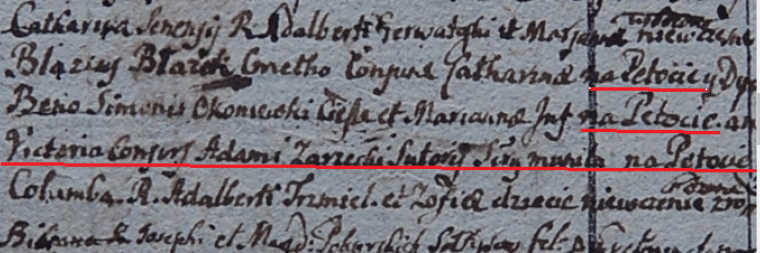

Figure 2: Baza PRADZIAD Results from Search for “Kowalewo”:

Figure 2 shows the top part of the search results; if you were to scroll down, there are a few more entries for “Nowe Kowalewo” below this. Note that there may be multiple parishes or registry offices with the same name that come up in the search results. However, when you click “more” at the far right, you can see which place is referenced by looking at the province, as shown in Figure 3:

Figure 3: “More” information on the first entry (“małżeństwa, 1808-1819, 1821-1890, 1911”) of the search results for Kowalewo:

Let’s consider these search results a bit more carefully. In Figure 2, we see that there are two collections of marriage records (małżeństwa) for Kowalewo. The first collection, boxed in red, covers marriages from 1808-1819, 1821-1890, and 1911. This collection belongs to the Archiwum Państwowe w Poznaniu Oddział w Koninie, as we can see from Figure 3 which comes up when we click, “more.” The second collection, boxed in green (Figure 2), covers marriages from 1828-1866. If we obtain more information about that collection (Figure 4), we realize that both collections are for the same Kowalewo, and they’re stored in different archives!

Figure 4: More” information on the second entry (“małżeństwa, 1828-1866”) of the search results for Kowalewo:

These records belong to the Diocesan Archive of Włocławek. Now, at this point you might be thinking, “Hey, isn’t this site supposed to be for the search engine for the STATE Archives? What’s a diocesan archive doing in the search results? And does this mean that I can expect to find all the holdings of the diocesan archives catalogued here?”

Welcome to the murky world of archival holdings in Poland. It would be great if there were one, central repository for all vital records in Poland, and if those holdings were completely catalogued, and if that catalogue were searchable online at only one website. But as my mother always says, “If wishes were horses, beggars would ride.” Although you may find that some diocesan archives have their holdings catalogued in Baza PRADZIAD, not all do. So I generally think of this as a catalogue for the holdings of State Archives, and if any diocesan results come up as well, that’s icing on the cake.

Now let’s go back to Figure 2. If you compare the boxes in red, blue and yellow, you see that these represent marriages, births (urodzenia) and deaths (zgony) for the same range of years. This makes sense, because frequently parishes would keep one parish register for each year, divided into three sections. Looking further at Figure 3, we notice the “dates” and “microfilms” underlined in purple and yellow, respectively, and herein lies the answer to the problem of our two-year gap in microfilmed and online records that exists from 1866-1867. As you can see from the text underlined in yellow, the archive also has those same microfilms, with the same gap. But their total collection, underlined in purple, includes years which are not available on microfilm. Whereas online and microfilmed records end in 1879, the archive also has births, marriages and deaths from 1880-1890, in addition to having births, marriages and deaths to fill that gap from 1866-1867.

How Do I Write to the Archives?

First, you want to make sure that the records aren’t available any other way (e.g microfilm or online), before you write, as archival research is generally slower and more expensive than obtaining records by these other methods. Popular websites for Polish vital records include Szukajwarchiwach (“Search in the Archives” or SwA), Metryki.GenBaza (or just, “GenBaza”), Metryki.Genealodzy.pl (or just “Metryki”), Poczekalnia (“Waiting Room,”), Genealogiawarchiwach (“Genealogy in the Archives”, or GwA), the digital collections for Poland available from the LDS, and others (mentioned on this list, starting at the bottom of page 3). If you’re not familiar with these sites and don’t know how to use them, visit us in Polish Genealogy and we’ll help you out. To determine whether your parish of interest has been microfilmed by the LDS, check the Family History Library catalog.

If it looks like your records of interest can only be found at one of the archives, you can send an e-mail to the address found in your Baza PRADZIAD search results (see above). You should write in Polish. Since this is professional correspondence, this is not a good time to break out Google Translate. Instead, use one of the letter-writing templates that are available online, either from the LDS or the PGSA. Alternatively, you can post a translation request in one of the Facebook groups (Polish Genealogy or Genealogy Translations) and a volunteer will probably assist you with a short translation, if you ask nicely.

How Much Will It Cost?

The cost of archival research depends on how many years they have to search, whether or not they find anything, and which archive you’re writing to. You might think it would be standardized across the country, but that hasn’t been my experience. I have paid as little as 4 zlotys ($1) to the Archive in Grodzisk for two records found after a search of marriages over a 12-year period, and as much as $30 to the Archive in Konin after a search of marriages over a 9-year period that turned up empty. (In that case, it’s possible that the girls died before reaching a marriageable age.) It’s important to have very clear, specific research goals in mind, however. Sending the archive a request that’s too vague, such as, “please search all your records for Kołaczyce for the surname Kowalski” or too broad, such as, “please search all your death records for Kołaczyce from 1863-1906 for Łącki deaths” is probably not advisable. For that kind of research, it would be better to hire a professional in Poland who can visit the archive for you in person.

What Happens When They Find My Records?

When the archive has completed their research, they will reply to notify you of the results. The letter or e-mail will be in Polish; if you need assistance with translating it, I would again recommend those Facebook groups (Polish Genealogy or Genealogy Translations). If they found records, they will summarize their findings, but you will not receive copies until you make payment. If they didn’t find anything, they will still charge you a search fee for the time they had to spend looking.

How Do I Make Payment?

The archives will only accept payment by direct wire transfer to bank account number specified in their correspondence. They do not accept personal checks, credit cards, cash, or PayPal. Here’s where it gets tricky: most U.S. banks charge high fees for international wire transfers. However, there are alternatives to paying your bank. You can set up a wire transfer with a company like Western Union or Xoom, where the fees are typically much lower. If you live in a community with a Polish travel agency, you can often ask them to wire money for you for a small fee. Or, you can ask a professional researcher in Poland to handle the transaction for you, and you can reimburse him or her via PayPal. (Be sure to add in a tip if the researcher does not specify a charge for his or her time).

When Will I Get My Records?

Again, your mileage may vary, based on the archive in question, but in general, I’ve gotten results within a week or two after payment has been made. Be sure to attach your payment receipt to your return e-mail to the archive. I’ve always received my records in the form of digital images sent via e-mail, but I’ve heard from others who say they’ve always received hard copies.

That’s pretty much all there is to it! Writing to archives in Poland doesn’t have to be an intimidating process, nor will it necessarily break the bank. As long as you have clearly defined research goals and a relatively small range of years for them to check, archival research can be quite affordable. If you’ve been on the fence about writing to an archive, I hope this encourages you to go ahead and give it a try. And if you do, please let me know how it turns out. Happy researching!

© 2016 Julie Roberts Szczepankiewicz