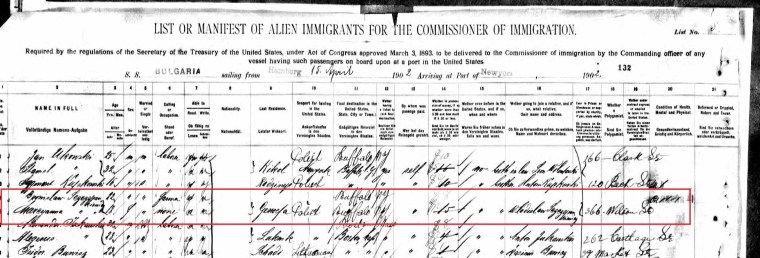

Those of us with ancestors who immigrated to America in the 19th and early 20th centuries know how valuable passenger manifests can be, as they often provide the name of the immigrant’s place of birth. We also know how frustrating it can sometimes be to find those immigrants in indexed databases such as Ellis Island and Ancestry. Today I’d like to review some basic concepts regarding passenger manifests, and then share a few tips for finding your ancestors in those databases.

Types of Manifests: Embarkation vs. Arrival

It helps to begin with an understanding of the manifests themselves and how they were created. There’s a persistent myth in American culture that names were changed at Ellis Island. This article explains more fully why that isn’t true, but the short version is that the manifests were recorded at the port of embarkation, and Ellis Island officials were merely working from those original lists. Many of these manifests recorded at ports of embarkation did not survive. For example, most of the Bremen lists were destroyed due to lack of space in the Bremen Archives. However, the Hamburg emigration lists recorded between 1850-1934 have largely survived, and sometimes it’s possible to find both the outgoing Hamburg manifest and the incoming Port of New York manifest for the same immigrant.

Types of Errors: Original vs. Transcription

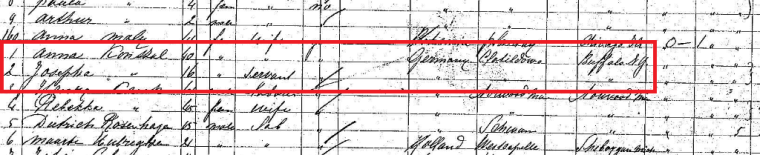

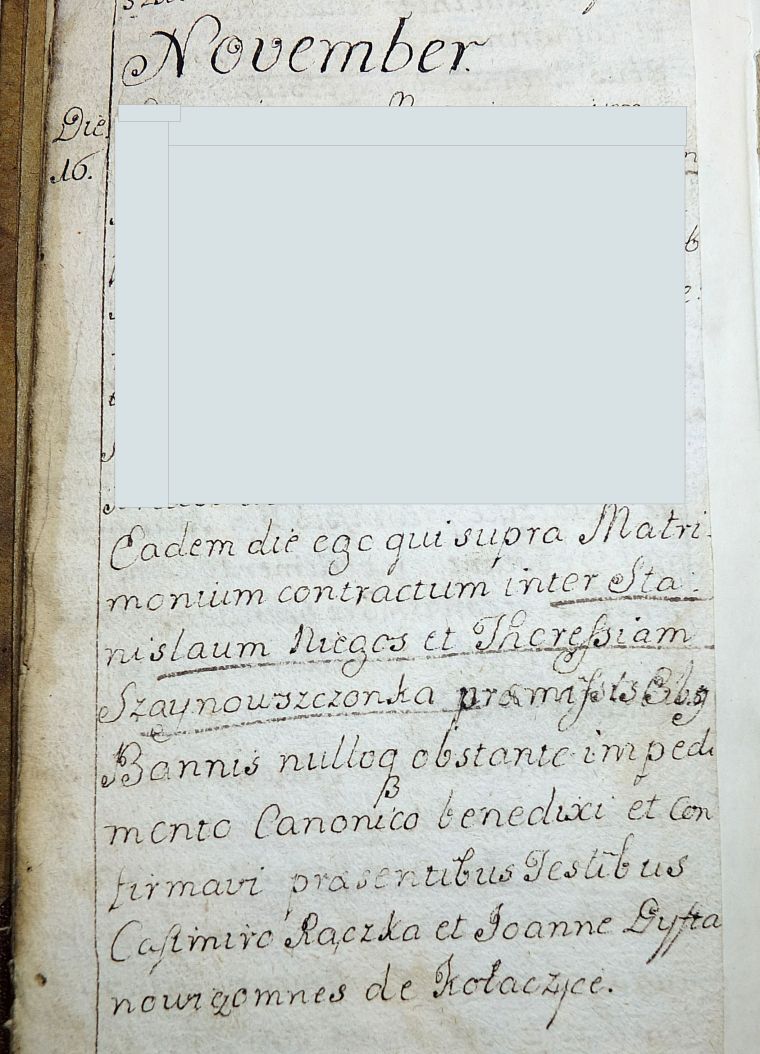

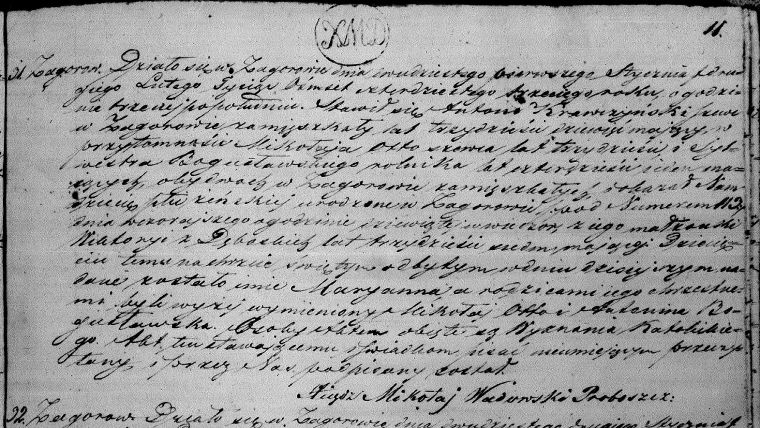

There are undoubtedly errors in spelling and transliteration that occurred on these passenger manifests, but most of the name changes that people attribute to “Ellis Island” were adopted by the immigrants themselves as part of their efforts to assimilate into American culture. In my experience, far more dramatic spelling errors were created during the process of transcribing and indexing the passenger manifests to create a searchable database, than occurred during the original recording of the manifests. I don’t want to place too much blame on the indexers here, as they’re faced with a formidable task. Anyone who’s ever looked at a passenger manifest knows that the handwriting can be cramped and illegible, the manifest might have been torn, taped, or faded, and the microfilmed image might be blurry or grainy. Combine this with the fact that you might see on the same page immigrants from a variety of different countries, each with its own language and maybe its own alphabet, and it’s immediately clear that indexers are brave and hardy heroes, indeed.

Faced with all these obstacles, how do we find our immigrant ancestors on those manifests?

1. Use wild-card searches.

If you have a subscription to Ancestry (or can access it at your local public library or Family History Center), you can search their immigration database using wildcard characters. Ancestry‘s directions state,

“An asterisk “*” replaces zero or more characters, and a question mark “?” replaces exactly one character. For example, a search for “fran*” will return matches on words like “Fran,” “Franny,” or “Frank.” A search for “Johns?n” matches “Johnson” and “Johnsen,” but not “Johnston.”

2. Try leaving off the surname entirely.

In cases where I suspect a surname has been butchered in the transcription, I sometimes omit it entirely, and search for the immigrant based on other identifying information. For example, I could search for my great-grandmother, Weronika Grzesiak, by looking for a female passenger named Weronika, born about 1876, stating Polish ethnicity, arriving about 1898.

3. Play with the search parameters.

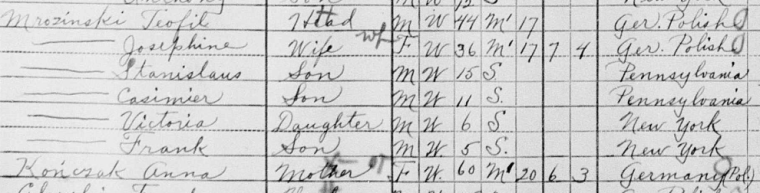

If your parameters are too specific, you get too few hits, but if they’re too broad, you get too many, so try tinkering with them one by one. Sometimes male passengers are marked as female and vice versa, sometimes first and last names are reversed, and that “race/nationality” box is tricky for Poles, who might be marked as Polish, Russian, German, or Austrian. Be flexible.

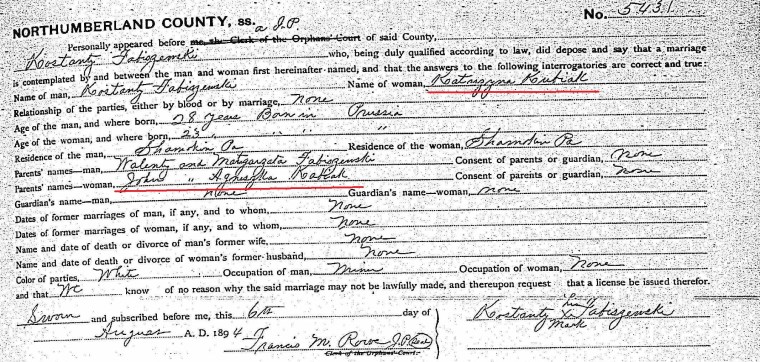

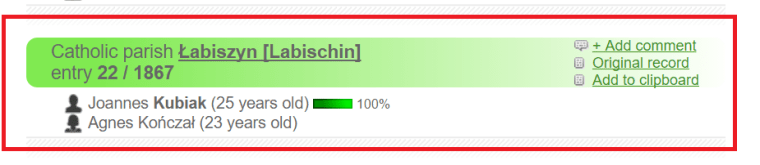

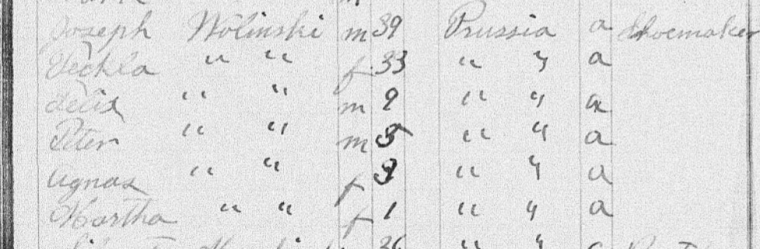

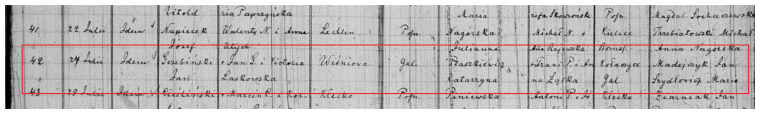

4. Determine your ancestor’s name at the time of immigration before you search.

I’d bet a million dollars that a Polish ancestor named “Walter Cherry” will not be listed under that name on his passenger manifest. There’s a good chance you’d find him under “Władysław Wiśniewski,” though. That’s because many of our ancestors adopted new given names, or new versions of their surnames, as part of their efforts to assimilate into American culture. Some common name changes among Polish-Americans were Władysław to Walter, Stanisław to Stanley, Czesław to Chester, Bronisław to Bruno, and Wojciech to Albert or George. For women, common changes include Jadwiga to Ida or Hattie, Władysława to Lottie or Charlotte, Pelagia to Pearl, and Bronisława to Bertha. These are generalizations, and it’s important to recognize that there were no hard and fast rules. You need to do research into your own family history to determine the names that your immigrant ancestors used. (See here for my story of my challenge in finding the passenger manifest for an immigrant who used Edward in the U.S. when his real name was Stanisław!) For Polish ancestors who settled in the U.S., try checking church records from the parish they attended here, as those are frequently a good clue to their original names.

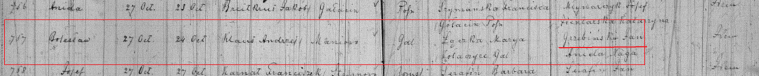

5. Familiarize yourself with spelling and pronunciation rules in your ancestor’s native language.

In Polish, “Szcz” is a common combination of two digraphs (sz and cz), and there are a lot of surnames that start this way. In contrast, surnames that start with “Lz” are quite rare (I found exactly one example, Lzarewicz, which belonged to exactly 1 person in Poland as of 1990, in this database). So when your search results at Ellis Island or Ancestry include results for passengers with names like “Lzczerba,” “Lzcrepaniak,” and “Lzcsepansky,” you can bet that those names are misspelled and actually start with “S.” In these examples, when I checked the original image of the manifest, those names were clearly Szczerba, Szczepaniak, and Szczepansky.

6. Databases index differently, so if you can’t find your ancestor in one database, check another.

My husband’s great-grandfather had a sister named Marcjanna Szczepankiewicz who was indexed on Ellis Island as “Marcyanna Sezezefsankiewiez” and on Ancestry as “Marcyanna Sczezyoankiemg.” On the manifest, the surname is clearly “Szczepankiewicz,” so this is a case of the indexers having no familiarity with Polish surnames. Even better, in looking up those examples, I came across one poor guy who was indexed on Ancestry as a 24-year-old Ruthenian woman named “Fazel Lzczzvca.” I took a look at the actual manifest, and the passenger was a 24-year-old Ruthenian man named Józef Szczyrba. I didn’t have the heart to see how he was indexed on Ellis Island, and I don’t know whether to laugh or cry.

7. Give Steve Morse’s site a try.

If you’re not familiar with Steve Morse’s website, you’re missing out. He’s got a variety of very helpful tools for genealogists, including resources for translations, DNA, searching census records, and a search portal for the different immigration databases (both free, like Ellis Island and Castle Garden, and paid, like Ancestry). I used to use his search portal all the time back in the late 1990s/early 2000s, because it was far superior to Ellis Island‘s search portal for the same data. But to be honest, a lot has changed since then, and both Ancestry and Ellis Island now offer fairly powerful, flexible search parameters that are comparable to Steve Morse’s. However, you may find that his search page is laid out in a more intuitive fashion, so it can’t hurt to try if you’re not having luck with the other search engines.

8. If you already know your ancestor’s hometown but you still can’t find his manifest, try searching according to place of origin.

This technique is not only useful for finding missing manifests, but also can sometimes be used to gain insight into the family groups in your ancestral village. For example, one of my ancestral parishes is Młodzieszyn in Sochaczew County, Poland. Records for Młodzieszyn were largely destroyed in World War II, leaving only records from 1885-1908. So, my understanding of my family history there is very incomplete. However, I’ve discovered that passenger records can offer a surprising amount of information to help fill in some of these blanks. Manifests for emigrants from Młodzieszyn have given me their names, approximate birth dates, and the names and relationships of contacts in the new world (often family members), as well as the names and relationships of family members still living in their former home town. Many of these emigrants were born before 1885 when existing birth records for Młodzieszyn begin, so their passenger manifests are incredibly useful in constructing family groups. Of course, one problem with this is that the hometown is just as likely to be misspelled as the passenger’s name, but it’s still worth a shot.

9. If your ancestor has a common name but he immigrated with other family members, try searching for the manifest using the family member with the least common name.

For example, “Nowak” is the most common Polish surname there is, so if your great-grandfather was Jan Nowak, you’ll probably have to wade through a lot of manifests to find the right one. But if you have reason to believe that he emigrated at the same time as his wife, Pelagia, try searching for her instead.

10. If your ancestor naturalized after 1906, get his naturalization papers first, then try to find his manifest.

I was really stuck trying to find a manifest for my husband’s great-grandfather Joseph Bartoszewicz. He was supposed to have come in with a large family group, and I’d tried pretty much all the tips I mentioned here, but I just couldn’t tease the data out of the search engines. However, he naturalized in 1914, and after 1906, Petitions for Naturalization included questions about the person’s arrival date in the U.S., the port of entry, and the name of the ship. I obtained Joseph’s naturalization petition, which told me that he arrived on 12 October 1890 in the Port of Philadelphia on the ship Pennsylvania. Great! Only I still couldn’t find him, using that date as an exact search term. Further investigation revealed that Joseph reported his arrival date inaccurately — the Pennsylvania did not arrive in Philadelphia on 12 October 1890, but rather on the 13th. I finally found Joseph and his family by browsing through the manifest page by page.

If you’ve been struggling to find the right passenger manifests for your family, know that you’re not alone. It can certainly be frustrating sometimes, and we’ve all been there. But persistence and flexible search strategies will usually pay off. As always, I’m happy to hear from other researchers, so if you try some of these strategies and they work for you, or if you’d like to offer other suggestions, please leave a note in the comments. Happy researching!

© Julie Roberts Szczepankiewicz 2016

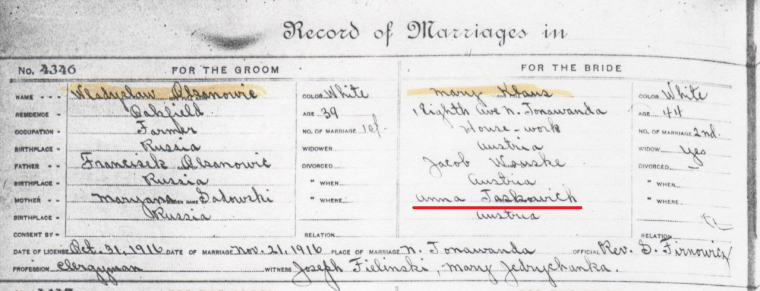

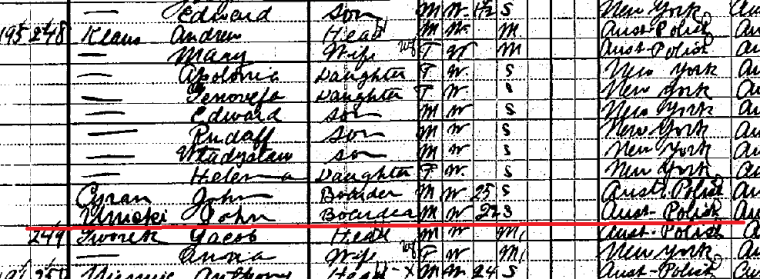

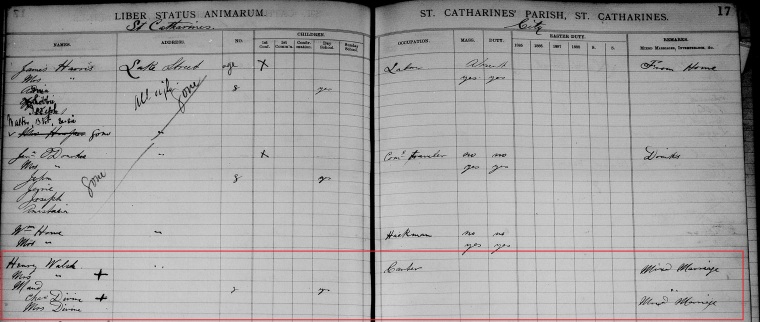

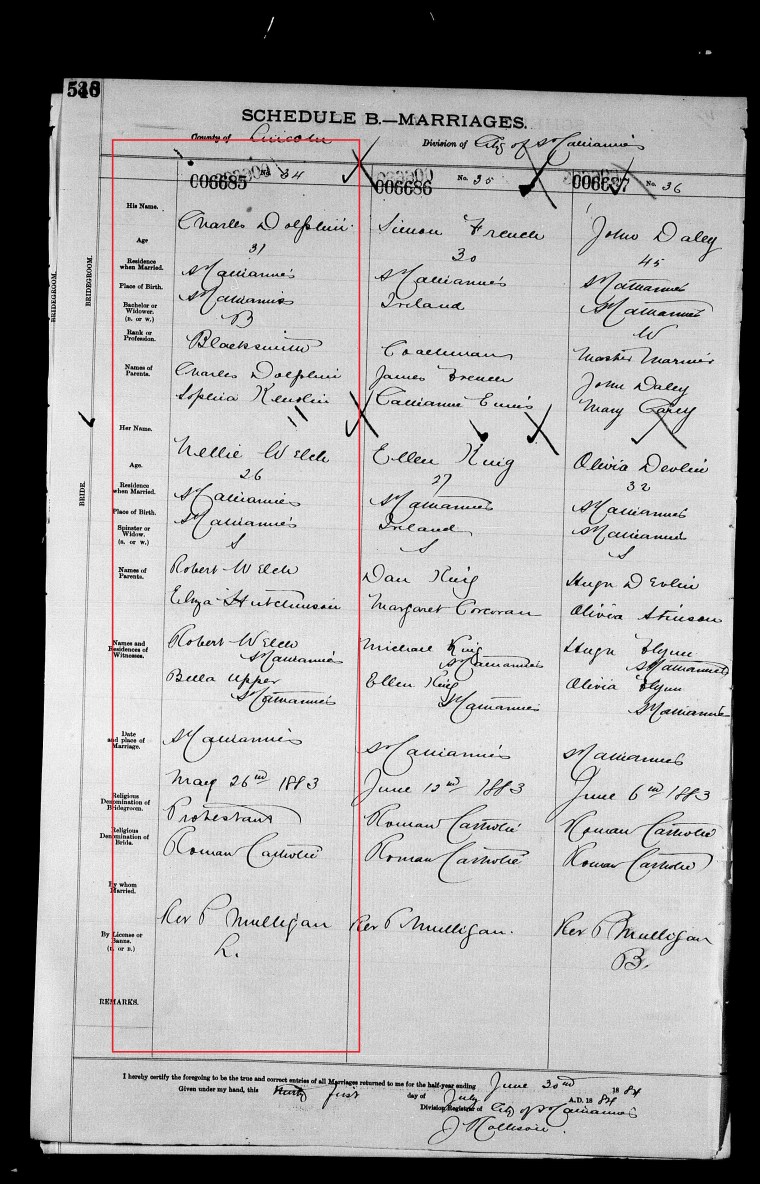

He wondered if I might have any insight into who the people were. I was excited to see the photo, and believed I could tell him exactly who these people were because Grandma Barth showed me this same photo before she died, and filled me in. I thought this photo would be a nice subject for a blog post, so I started to gather a bit of background documentation to provide some insight into the lives of the people shown here. In the process, I’ve discovered that things aren’t really what they seemed, and maybe — just maybe — Grandma might have been wrong about a thing or two.

He wondered if I might have any insight into who the people were. I was excited to see the photo, and believed I could tell him exactly who these people were because Grandma Barth showed me this same photo before she died, and filled me in. I thought this photo would be a nice subject for a blog post, so I started to gather a bit of background documentation to provide some insight into the lives of the people shown here. In the process, I’ve discovered that things aren’t really what they seemed, and maybe — just maybe — Grandma might have been wrong about a thing or two.