Recently, I wrote about census records in Poland, and the kinds of census records one might find. One type of census record that I mentioned is called the status animarum in Latin, and it’s a parish census that the pastor would conduct annually as he took stock of his parishioners’ spiritual well-being. These types of censuses were conducted throughout the Catholic Church, not just in Poland. Some of them happen to be available online — namely, parish census records from the Cathedral of St. Catherine of Alexandria in St. Catharines, Ontario, which was the home parish of my Walsh ancestors.

Meet the Walshes

The featured photo is a copy of an old tintype photo of four generations of the Walsh family, circa 1905. On the far left is Elizabeth (née Hodgkinson) Walsh (1818-1907), my great-great-great-grandmother, and on the far right is her son (my great-great-grandfather), Henry Walsh (1847-1907). Next to Henry is his oldest daughter, Marion (née Walsh) Frank (1878-1954), and next to her is her daughter, Alice Marion Frank. The image was cleaned up a bit courtesy of Jordan Sakal in the Genealogists’ Photo Restoration Group on Facebook.

The Walshes were an interesting bunch. My great-great-great-grandfather, Robert Walsh (1808-1881), was a Roman Catholic immigrant from Ireland to Canada who arrived some time before 1840 and worked as a tailor. Around 1840, he married Elizabeth Hodgkinson (1818-1907), an Anglican native of Ontario, and a granddaughter and great-granddaughter of Loyalists. Census records show that Robert and Elizabeth had 9 children: B. Maria, James George (later known as George James), Henry, Mary Ann, Robert, Elizabeth, Ellen (also known as Nellie), Thomas J. (baptized as John), and Joseph P. (baptized as Peter Joseph). Unfortunately, baptismal records have only been discovered for three of these: Elizabeth, Thomas J., and Joseph P., all of whom were baptized in the Cathedral of St. Catherine of Alexandria. It’s likely that their parents were married there as well. The parish was certainly in existence circa 1840 when the Walshes were married, but unfortunately, early records were destroyed when an arsonist burned down the original wooden church in 1842.1 No one seems to know what became of the records created after the fire, between 1842 and 1851. The earliest records that have survived date back to 1852 (baptisms and marriages only). Apparently, duplicate copies of the parish registers were never made, and neither the parish itself, nor the archives for the dioceses of Toronto (to which the parish belonged before 1958) or St. Catharines (to which the parish belonged after 1958) is in possession of any records from before 1852.2,3,4

As is evident from the list of their children’s names, the Walsh family had a propensity for switching first and middle names, and they also used variations of their surname indifferently, appearing as Walsh, Welsh, and Welch. One example of this can be seen in Figures 1 and 2, which show the grave marker that Elizabeth Walsh shares with her husband and youngest son (Joseph P), in comparison with her newspaper death notice.

Figure 1: Walsh monument in Victoria Lawn Cemetery for Robert, Elizabeth, and youngest son Joseph P. Walsh. The inscription for Elizabeth reads, “Elizabeth/Wife of/Robert Walsh/Died/Jan. 1, 1907/Aged 89 Years/Rest in Peace.” Photo courtesy of Carol Roberts Fischer.

Although the name appears as “Walsh” on the family monument, both her newspaper death notice5 and her death certificate6 report her name as Elizabeth Welch (Figure 3):

Figure 2: Death notice from the Buffalo Evening News for Elizabeth Welch, 3 January 1907.5

With so much variation in spellings of names, and with a surname that is so common to start with, particularly in St. Catharines, which was home to a large Irish immigrant population, one must proceed with caution when examining any records that might potentially pertain to this family. Canadian census records, city directories, and church records all show a number of different Walsh, Welsh and Welch families which may or may not be related to my own. This parish census collection was no exception.

Identifying the Walsh Family in the Parish Census

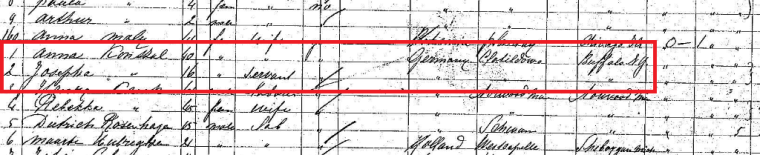

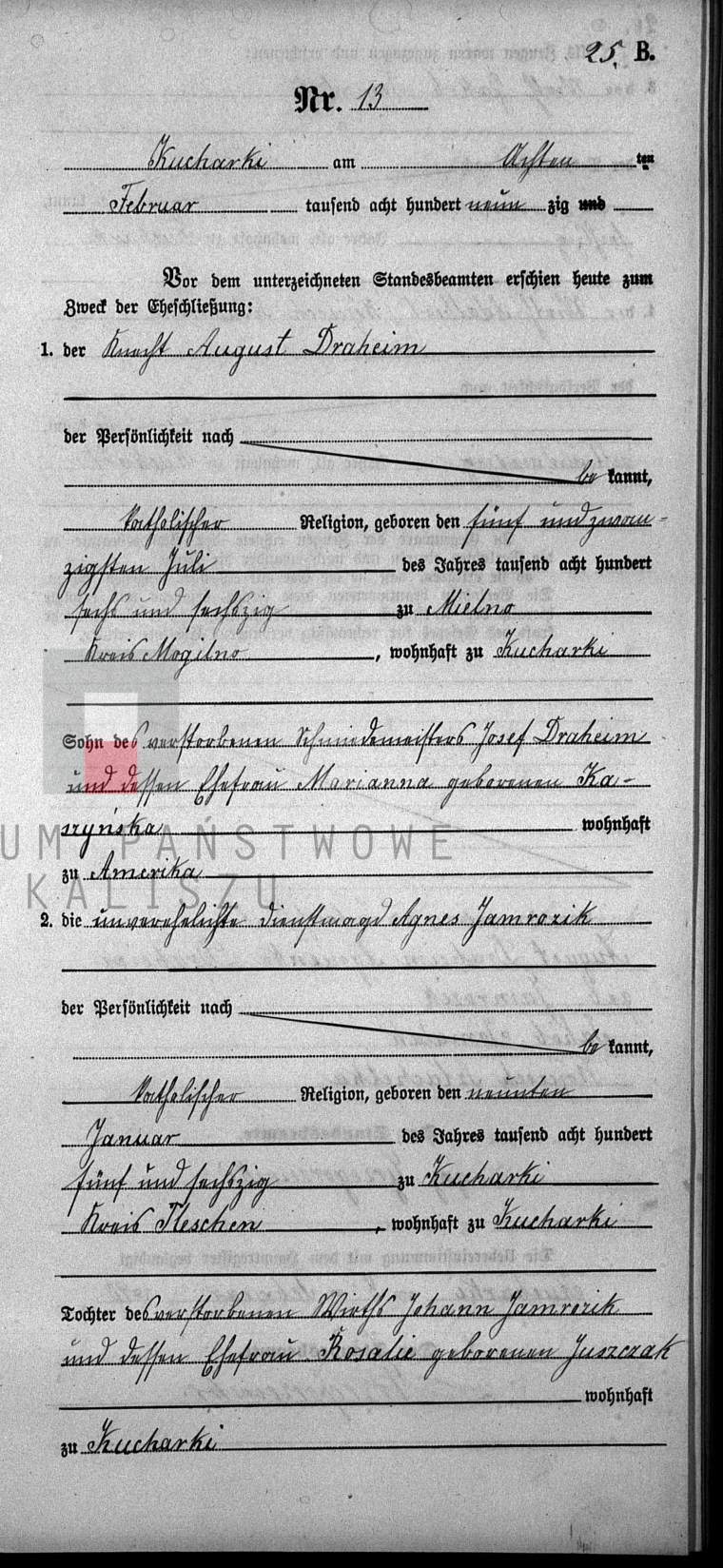

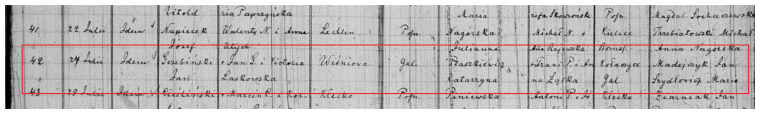

Once I started searching the parish census, it didn’t take long to find this record (Figure 4):

Figure 4: Walsh family in the 1885-1886 Status Animarum for St. Catherine of Alexandria parish, St. Catharines, Ontario.

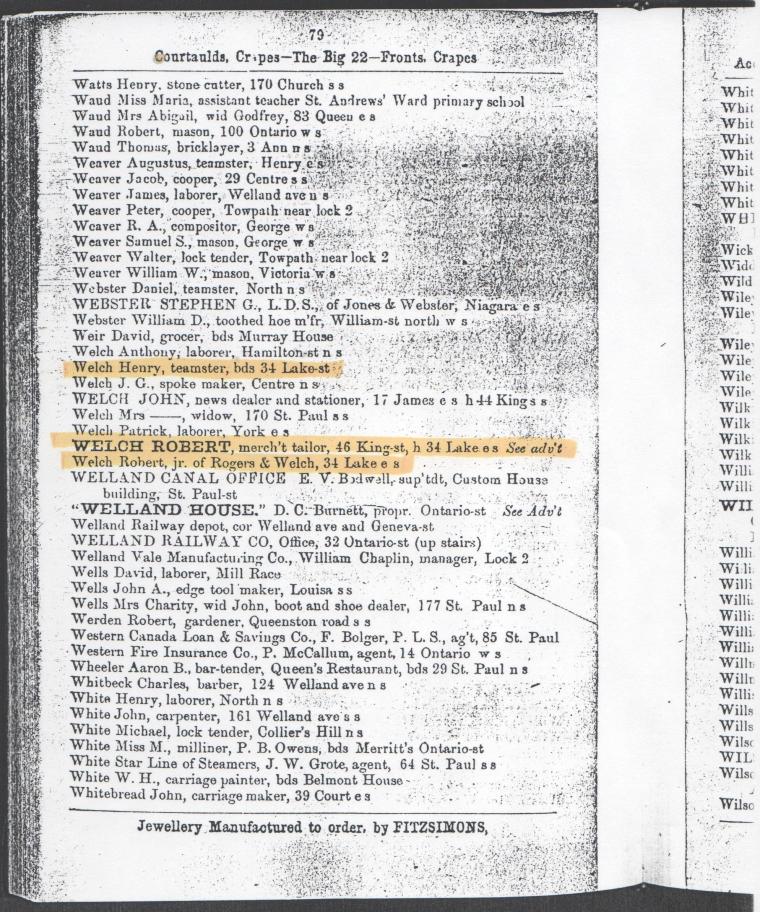

This shows a Mrs. Walsh with sons Thomas and Robert. Not a lot of information to go on, but I’m sure these are mine, for several reasons. First, Mr. Walsh is not mentioned, consistent with the fact that the census is from 1885-1886 and “my” Robert Walsh died in 1881. Second, the entries on this page all seem to be families living on Lake Street, which is where my Walshes were listed on several city directories as having residence (Figure 5):7

Figure 5: “Welch” entries in St. Catharines City Directory, 1877-78.7

The above entries for “Welch” include Robert, a merchant tailor, and his sons, Henry, a teamster, and Robert, Jr., who was co-owner of the “Rogers and Welch” livery service, all living at 34 Lake Street. This is consistent with the parish census, which indicates that the mother, “Mrs. Walsh,” is (or was) a tailor. The fact that the word “tailor” is crossed out may suggest a correction made by the priest, due to the fact that her late husband was a tailor but she herself was living as a dependent of her sons at that point. Thomas was originally recorded as being occupied in the livery business, but this, too, is crossed out, and corrected to “tailor.” The second son, Robert, is recorded as being employed in the livery business, consistent with the information from the city directory.

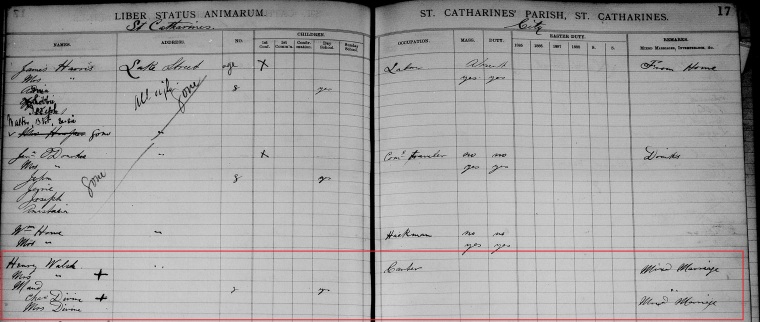

The family’s religious observance is recorded in the next column with Elizabeth being described as “careless” in her Mass attendance, while her sons were apparently not practicing. Perhaps by way of explanation, the priest noted in the final column that she was “a convert” and added, “three mixed marriages: James — Main Street/Henry Lake Street/Mrs. Divine at Henry’s.” This notation points to the other ecumenical marriages in the family at that time: Elizabeth’s son, James George married Jane Lawder, a Protestant; her son Henry married Martha Agnes Dodds, also Protestant, and daughter Ellen (“Nellie”) married Charles DeVere (recorded here as “Divine”). On the preceding page in the book, we find the family of Henry Walsh (Figure 6):

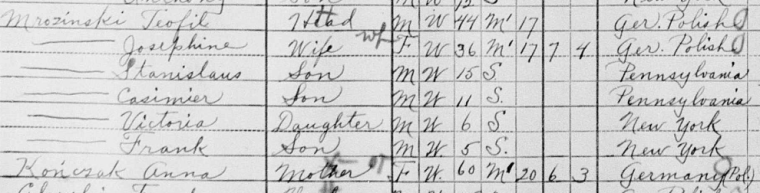

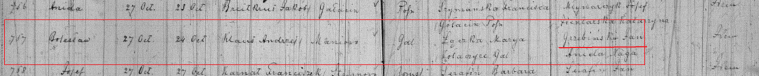

Figure 6: Henry Walsh family in the 1885-1886 Status Animarum for St. Catherine of Alexandria parish, St. Catharines, Ontario.

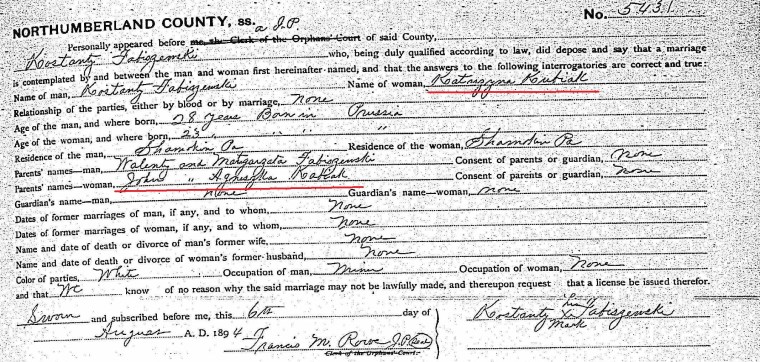

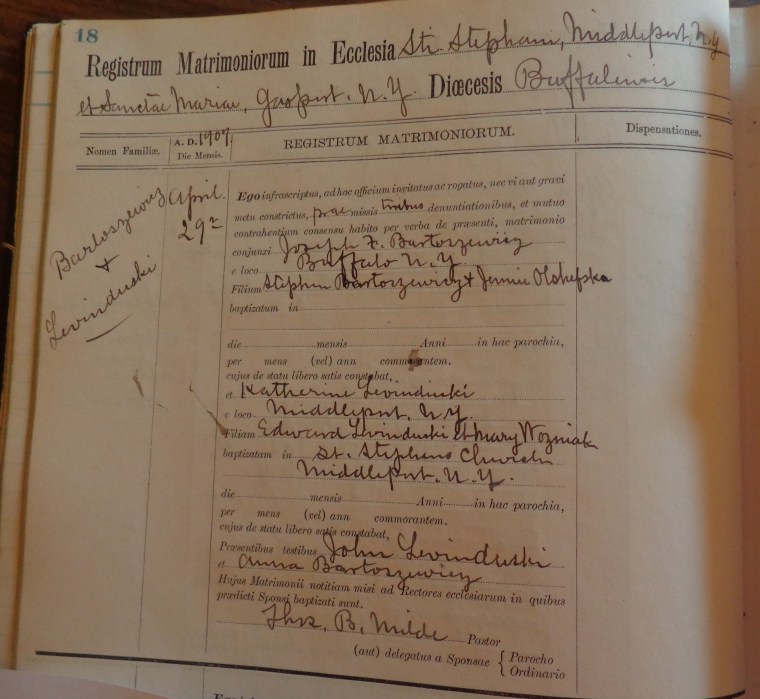

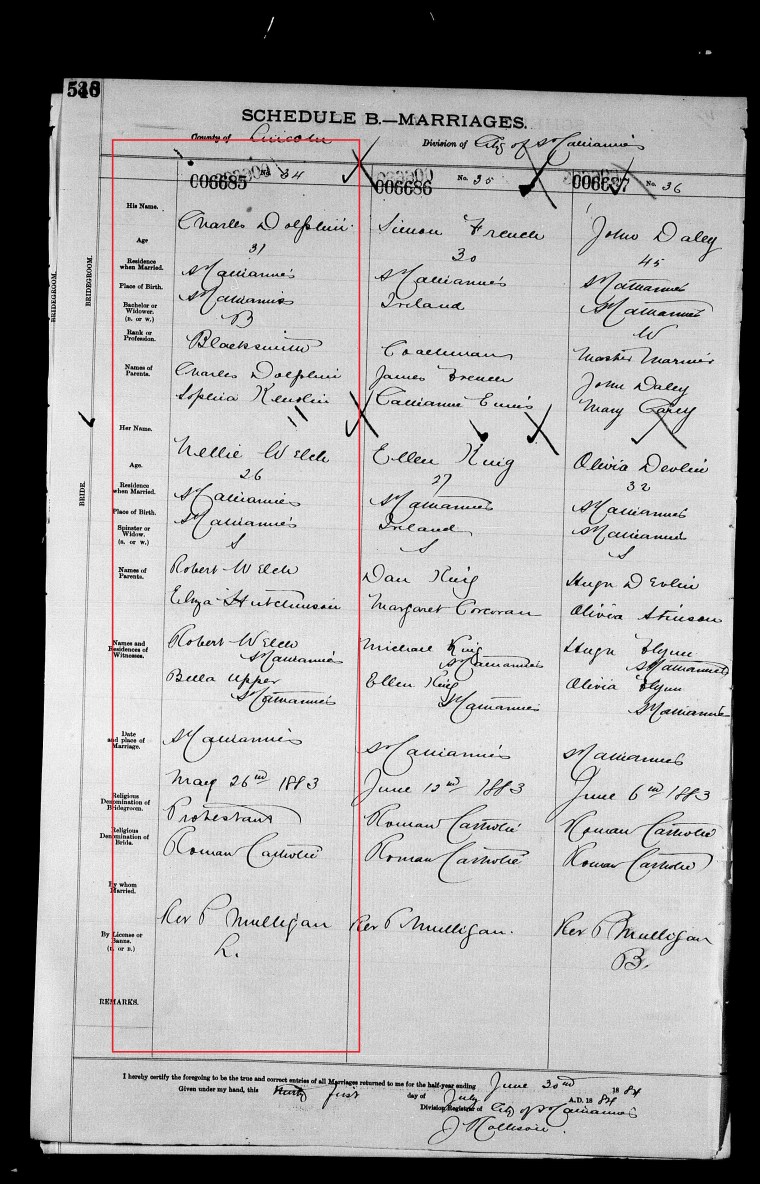

Henry Walsh is listed as a carter here, consistent with other sources which stated his occupation as teamster. His wife’s name is not stated here, but his wife, Martha Agnes Dodds, was Protestant. The child living with them, “Maud,” is noted to be 8 years old and attending day school. This suggests that “Maud” is their oldest daughter, Marion, who was born in 1878. It’s unclear why none of their other children are mentioned, since Henry and Martha’s daughters Clara and Katherine were born in 1880 and 1883, respectively. The other couple living with them, “Chas. Divine and Mrs. Divine,” are undoubtedly Henry’s sister, Ellen “Nellie” and her husband, Charles DeVere, also known as Charles Dolphin or Charles Dolfin. Although this is another fine example of variant surname spellings run amuck, their civil marriage record (Figure 7) shows that the groom was Protestant and the bride was Catholic, consistent with the notation about a “mixed marriage” on the parish census record.

Figure 7: Civil marriage record for Nellie Welch and Charles Dolphin

Although the original parish census entry for “Mrs. Walsh” mentioned the family of James Walsh, living on Main Street, there is no corresponding entry for this family in the parish census book, nor was Main Street listed as an address for any families in the census book. It’s possible that these addresses would have belonged to another parish in St. Catharines since there were several Catholic parishes in St. Catharines by the mid-1880s.

Parish census records are unlikely to provide any earth-shattering new data in areas in which other census records survive. Nonetheless, they may offer some useful insights to add to our understanding of our families within their local communities. If you have Catholic ancestors from St. Catharines, be sure to check out this collection to see what you might find!

Sources

1 “Roman Catholic Diocese of Saint Catharines.” Wikipedia. Accessed October 21, 2016. https://www.wikipedia.org/.

2 Price, Rev. Brian. Archives of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Kingston. E-mail message to author. July 7, 2016.

3 Sweetapple, Lori. Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto. E-mail message to author, July 11, 2016.

4 Wilson-Zorzetto, Liz. Archives of the Roman Catholic Diocese of St. Catharines. E-mail message to the author, July 14, 2016.

5 Death notice for Elizabeth Welch, January 3, 1907, http://fultonhistory.com/Fulton.html, Buffalo Evening News, Buffalo, New York, online images.

6 Buffalo, Erie, New York, Death Certificates, 1907, #198, record for Elizabeth Welch.

7 Leavenworth, E.S., ed. “Welch” in Directory of St. Catharines, Thorold, Merriton, and Port Dalhousie, for 1877-78. St. Catharines: Leavenworth, 1877. 79.

© Julie Roberts Szczepankiewicz 2016

He wondered if I might have any insight into who the people were. I was excited to see the photo, and believed I could tell him exactly who these people were because Grandma Barth showed me this same photo before she died, and filled me in. I thought this photo would be a nice subject for a blog post, so I started to gather a bit of background documentation to provide some insight into the lives of the people shown here. In the process, I’ve discovered that things aren’t really what they seemed, and maybe — just maybe — Grandma might have been wrong about a thing or two.

He wondered if I might have any insight into who the people were. I was excited to see the photo, and believed I could tell him exactly who these people were because Grandma Barth showed me this same photo before she died, and filled me in. I thought this photo would be a nice subject for a blog post, so I started to gather a bit of background documentation to provide some insight into the lives of the people shown here. In the process, I’ve discovered that things aren’t really what they seemed, and maybe — just maybe — Grandma might have been wrong about a thing or two.