Please note: While the original version of this post appears below, a more comprehensive tutorial was created in 2018 and can be found in three linked parts, starting here.—JRS

If you haven’t stopped by the popular Polish vital records database Geneteka lately, you’re in for a real treat. Our friends at the Polskie Towarzystwa Genealogiczne (PTG, the Polish Genealogical Society) have made some significant improvements to the search interface, making a good thing even better. This seems like a good time for a tutorial on how to use Geneteka, for those of you who might be unfamiliar with it. I’ll highlight some of the improvements along the way, for those of you who already have some experience with this database.

What is Geneteka?

So what is Geneteka? As mentioned, it’s a database of Polish vital records that have been indexed by surname, from parishes and registry offices which are grouped according to the contemporary province in Poland in which they lie. Geneteka is part of a family of websites sponsored by the PTG. Each of these “sister sites” is wonderful in its own way, and several of these will probably be discussed in more detail in future blog posts. (One of these, Metryki, was already discussed in one of my previous blog posts.) But today, let’s focus on Geneteka.

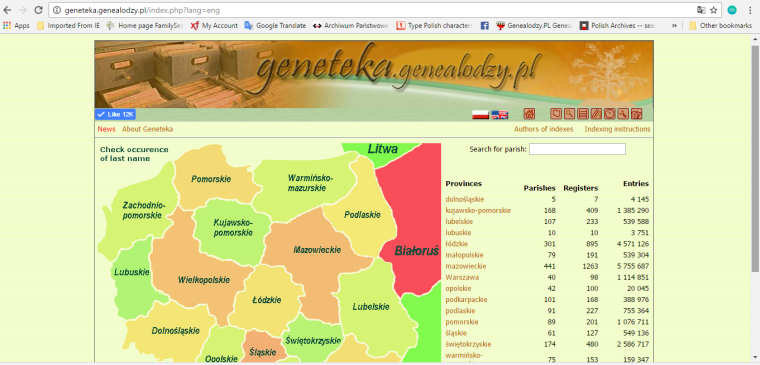

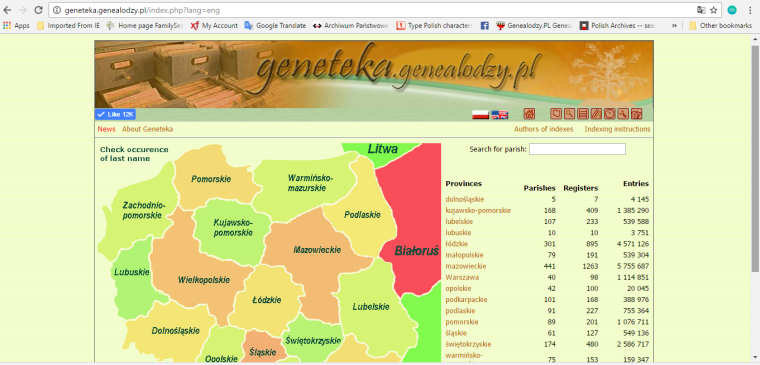

At Geneteka’s home page, not much has changed. Here’s the page with English chosen as the language:

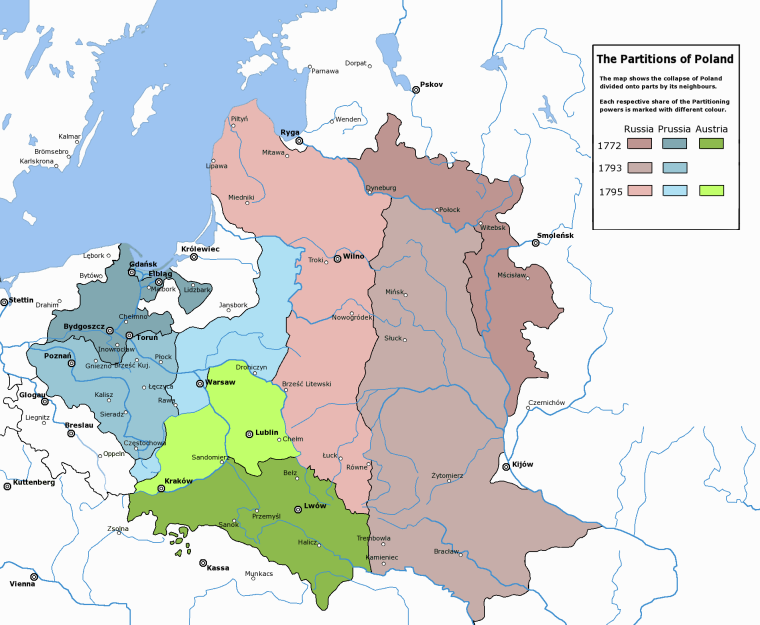

This main page offers an interactive map where we can click on the name of a province of interest, as well as a search box near the top right, where we can type in the name of a parish to see if records for that parish have been indexed here. Some indexes for locations in Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine are also included. Below that search box, there is a list of Polish provinces. Click the name of a province to search for records from that entire province, as an alternative to clicking it on the map. To the right of the list of provinces, there is information on the number of parishes and civil registry offices that have been indexed for each province, as well as the total number of indexed records. From this we can get a feel for how good the coverage is for each particular area. For example, there are fewer than 300 parishes and registry offices that have been indexed for the Lesser Poland province (województwo małopolskie), with about half a million vital records, whereas there are over 1,700 parishes and registry offices indexed for the Mazovia province (województwo mazowieckie), with close to 6 million records.

It’s important to remember that Geneteka is still a work in progress. New indexes are being added weekly, all created by volunteers, who are the unsung heroes of the genealogy community, and to whom we owe an enormous debt of gratitude. However, many parishes have not yet been indexed at all, or have not yet been indexed for the particular range of years needed for one’s research. Therefore I still recommend that you determine your immigrant ancestor’s place of origin first, using records created in his new homeland, rather than trying to make the leap back to Poland by checking Geneteka first. It’s all too easy to attach spurious ancestors to one’s family tree by haphazard searches in Geneteka, especially if the surname is common, or there is a lack of identifying information such as parents’ names for the immigrant ancestor.

Starting a Search

With that caveat out of the way, we can move on to the nitty-gritty. Let’s take the example of a search for ancestors in Mazowieckie province. We click “Mazowieckie” on the map or in the list of provinces, and arrive at this screen:

Immediately, a number of changes are apparent to those who have used this resource previously, but let’s start at the top. In the past, if one wished to use the site in English, it was necessary to change the language at the home page. If a search was begun within records for a province, and one tried to switch to English, one was returned to the home page and all search results were lost. Now it’s possible to switch languages at any time during the search process, which is very convenient for those who might not be completely comfortable with Polish.

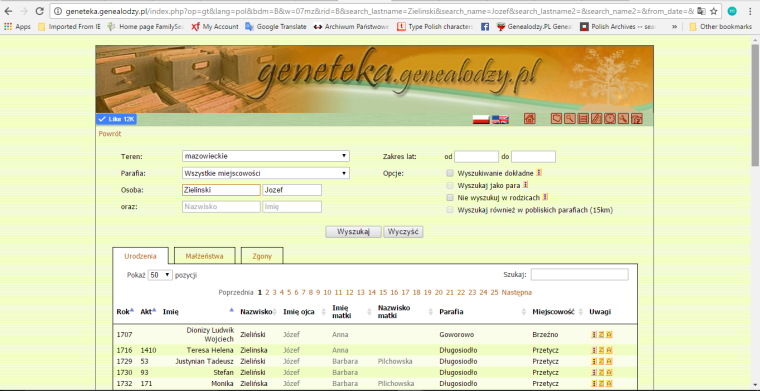

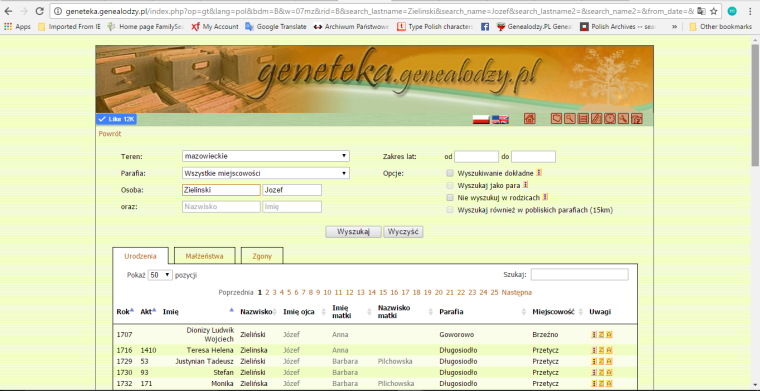

Next, we see that it is now possible to search using both a person’s surname (Nazwisko) as well as his given name (Imię). Note that diacritics aren’t important here, so you can type “Jozef Zielinski” and still find results for Józef Zieliński. Assuming we add no other identifying information, here’s what that search would produce:

As you can see, there are over 25 pages of results, because as it happens, Zieliński is a very common Polish surname. As you look through the results, you’ll notice that the search algorithm is also designed to return not only the target name, but also names that are phonetically similar. This can be very helpful because surname spellings weren’t always consistent until perhaps the 1930s. However, if you only wish to see results for “Zieliński,” you can check the box for “Exact Search”/”Wyszukiwanie dokładne” and only results for “Zieliński” will be returned. Note that you still don’t have to enter correct diacritics even with an “exact” search: typing “Zielinski” will still give you results for “Zieliński.”

It should be noted that the “exact search” feature will also produce gender-specific results in cases where a given name is not specified. For example, if I search for “Zieliński” with no given name specified, I get even more results, but they’re for both Zieliński and Zielińska, as well as approximate phonetic matches. Searching for “Zieliński” with the “Exact Search” box checked will not only eliminate phonetic matches, it will also eliminate results for feminine surnames. Obviously, as soon as I specify a given name, I’m also excluding results for the opposite sex.

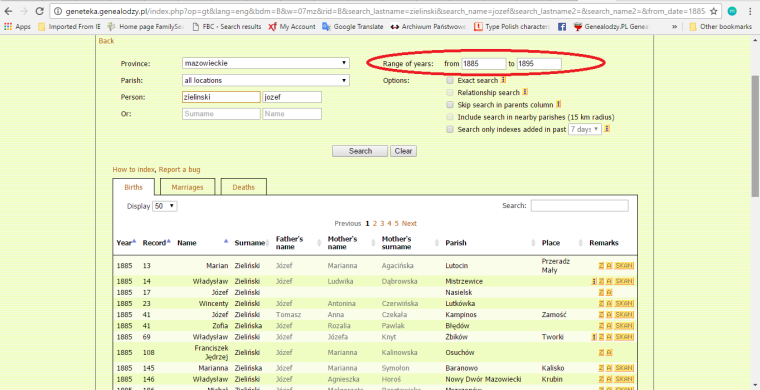

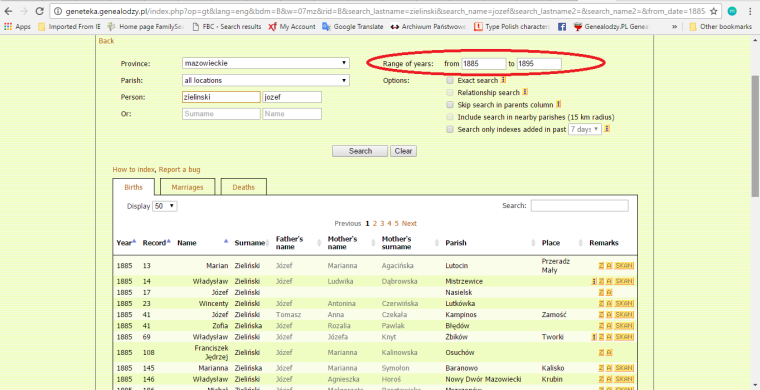

Results can be narrowed in other ways as well. At the top near the left, there is an option to narrow the range of years for which results are returned.

So by entering both a given name and narrowing the range of years, we’ve already cut our search results down to a mere 5+ pages. Progress! Of course, one of the best ways to narrow results is by using a second surname for the search. In this case, I know my great-grandfather Józef Zieliński was the son of Stanisław Zieliński and Marianna Kalota. So even if I don’t narrow the range of years at all, if I just enter his mother’s maiden name in the second search box, I can immediately zero in on his family.

Note that I didn’t bother to specify both his parents’ given names, even though I knew them. That’s because making a search too specific can lead you to miss documents that actually are for your family, but might have been recorded incorrectly (e.g. mother’s name written as Anna instead of Marianna). Some priests were much more careful about those details than others, so a good researcher must learn to critically evaluate all the data in a source to determine whether such an error is likely, or whether the evidence points to some other explanation, such as a second marriage.

Understanding the Search Results

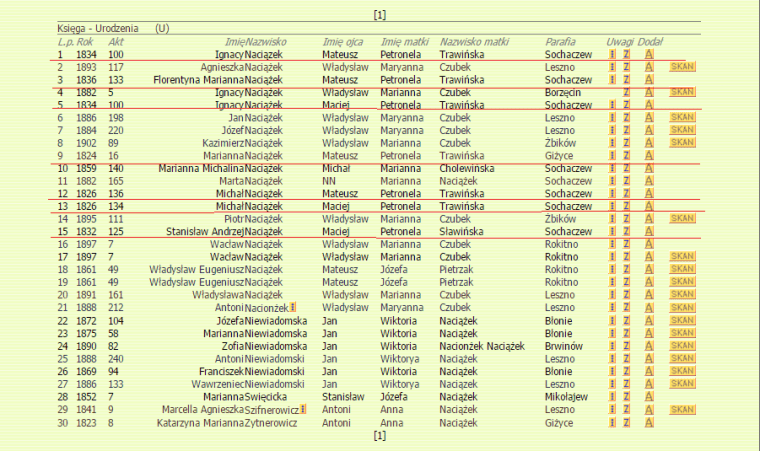

Let’s take a closer look at how these results are displayed:

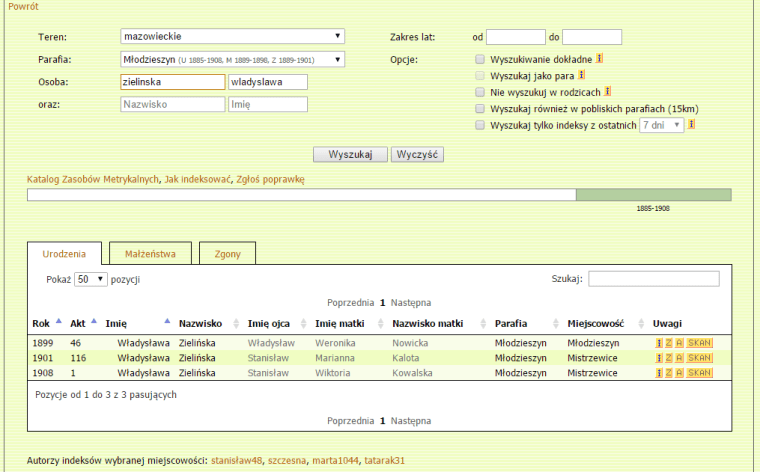

The first thing we notice — another recent improvement to Geneteka’s search interface — is that results for births, marriages and deaths appear on separate tabs, so it’s no longer necessary to search each type of vital event separately. The search algorithm is looking for any vital records which mention both surnames, Zieliński and Kalota, in any of the indexation columns. Note that records which might mention one of these names as a witness or godparents will not be returned, because at present, indexers are not instructed to include those data on the spreadsheet. On the births page, the results consist of baptismal records for the children of Stanisław Zieliński and Marianna Kalota. The columns report the year and the record number for each entry, as well as both the parish, and the place within that parish, where the vital event occurred. In this case, we see that the first six births were recorded in Mistrzewice, while the last four were recorded in the neighboring parish of Młodzieszyn — even though the next column tells us that each child was still born in Mistrzewice.

So how do we interpret that? Does this change in parishes suggest that our ancestors could pick and choose what parish they baptized their child in, much as we do today? No. It’s important to remember that Roman Catholic priests were also civil registrars in those days. Each village was assigned to a particular parish, and when a birth or death occurred in that village, villagers were required to report it to the parish in which the event occurred. In this case, it’s a bit of an historical sidenote, but this article explains that the parish in Mistrzewice was closed in 1898 and the village was transferred to the parish of Młodzieszyn. The timing explains perfectly the results we see here, wherein Władysław Zieliński was born and baptized in Mistrzewice in 1897, but his brother Jan was born in Mistrzewice and baptized in Młodzieszyn in 1899. So, if you see a sudden change in parish but the entry indicates that your ancestors’ village has remained the same, you may want to investigate the history of the parishes in that area to detect a reassignment or the establishment of a new parish.

Getting back to the discussion of Geneteka search results, you’ll notice that there are some little yellow “infodots” in the “Remarks/Uwagi” column on the far right. If you hover your cursor over each of them, additional information is revealed. For example, in the first entry for Franciszek Zieliński, hovering over the “i” reveals his exact date of birth, 16 September 1886.

Similarly, hovering over the “Z” indicates the name of the archive that holds the original record which was indexed here. In this case, originals are at the Grodzisk branch of the State Archive of Warsaw. This is not to suggest that the copies might not also be found some other way, such as at one of the online repositories, or on microfilm from the FHL. In this case, there is a “scan” button which we can click to obtain a scan of this vital record. Hovering over the “A” reveals the name of the volunteer indexer to whom we owe our debt of gratitude.

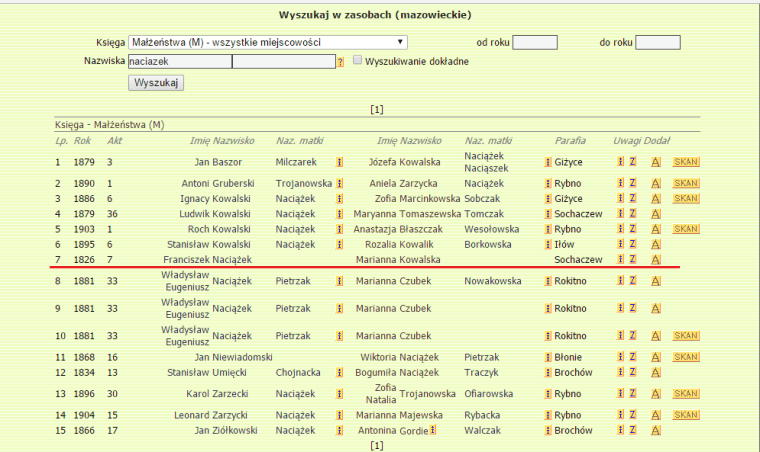

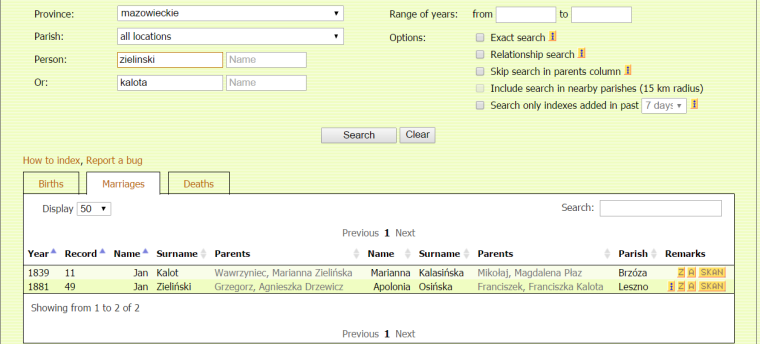

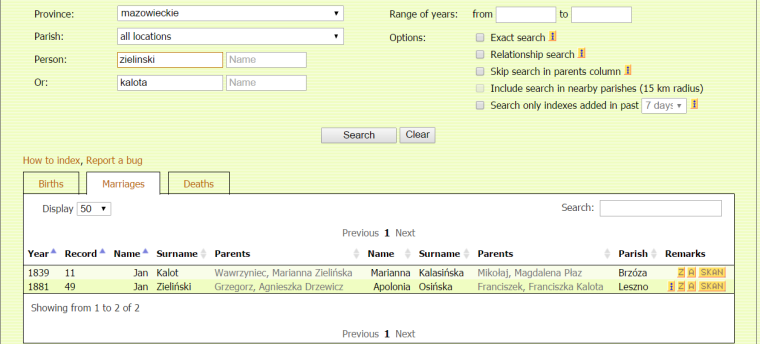

Let’s take a look at the results obtained under the “marriages” tab for this same search.

It’s evident here that neither of these marriages pertains to my family. The basic search algorithm looks for the names “Zieliński”and “Kalota” or approximate phonetic variations thereof, in any data field from the original indexing spreadsheet. So in the first instance, it picked out a record for which the groom was Jan Kalot and his mother was Marianna Zielińska, from a marriage that took place in 1839 in the parish of Brzóza. In the second case, the algorithm returned the marriage record from Leszno for a groom named Jan Zieliński and his bride, Apolonia Osińska, whose mother was Franciszka Kalota. This is where another one of Geneteka’s new search options comes in very handy. Suppose you’re looking for a Zieliński groom and a Kalota bride, and you want the algorithm to ignore any results with those surnames in the fields for parents of the bride and groom. In that case, you can tick the box for “skip search in parents column/Nie wyszukuj w rodzicach.” If this search is repeated with that box ticked, there are zero search results, as expected. However, in other cases, it could be used to refine the search hits and reduce the extraneous results that are reported.

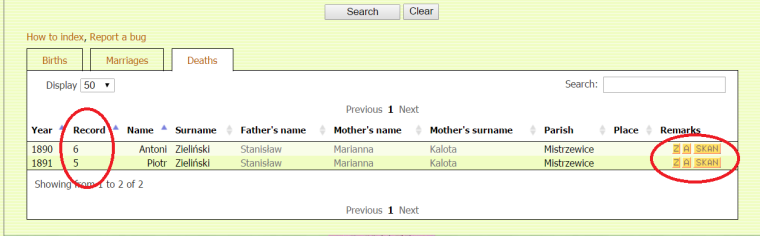

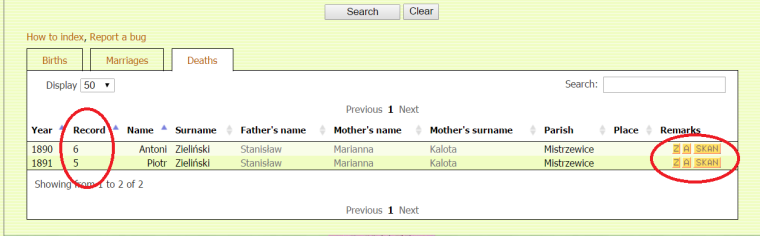

Let’s take a look at the results returned under the “deaths” tab before we move on to a further discussion of the new search tools.

These results aren’t too different from what we’ve seen previously, but you’ll notice that under the “remarks” column, there’s no “i” column that provides the precise date of death. In fact, as you explore Geneteka in more detail, you’re likely to notice that the content of each index varies quite a bit. Some indexes have scans attached, some do not. Some include only the names of the baptized child, the deceased, or the bride and groom, along with the year, the parish, and the record number, but no other identifying information, such as parents’ names. This is because Geneteka is an evolving entity. In its early days, these digital indexes were created from the year-end indexes that the priests made within each parish register. Presently, there is more of an emphasis on making the indexes as complete as possible, utilizing information from the records themselves.

Obtaining Scans

Having successfully identified some records of interest, how do we obtain those scans? Obviously, we start by clicking the “skan” button, but we also want to make note of the record number for the record of interest. For example, if we want to obtain the death record for Piotr Zieliński from 1891, we note the record number, 5, circled here:

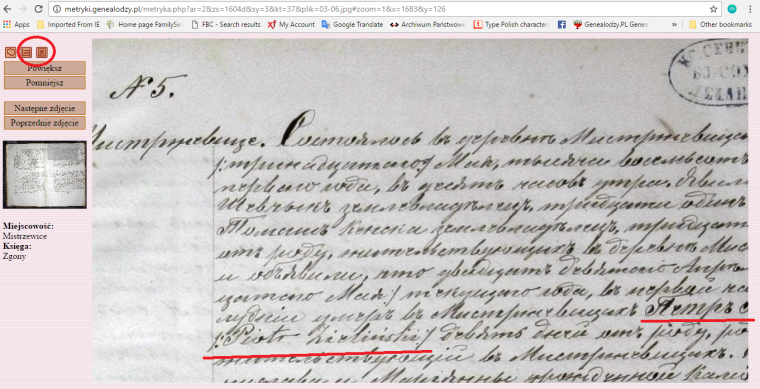

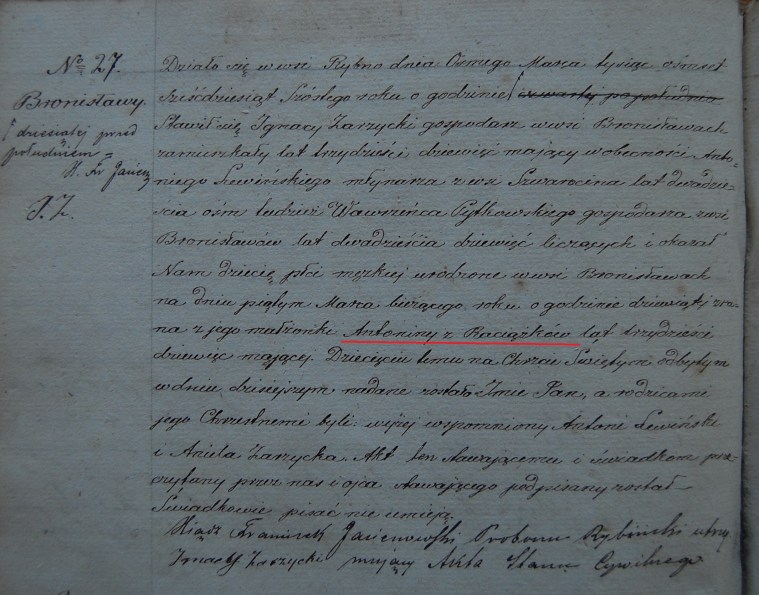

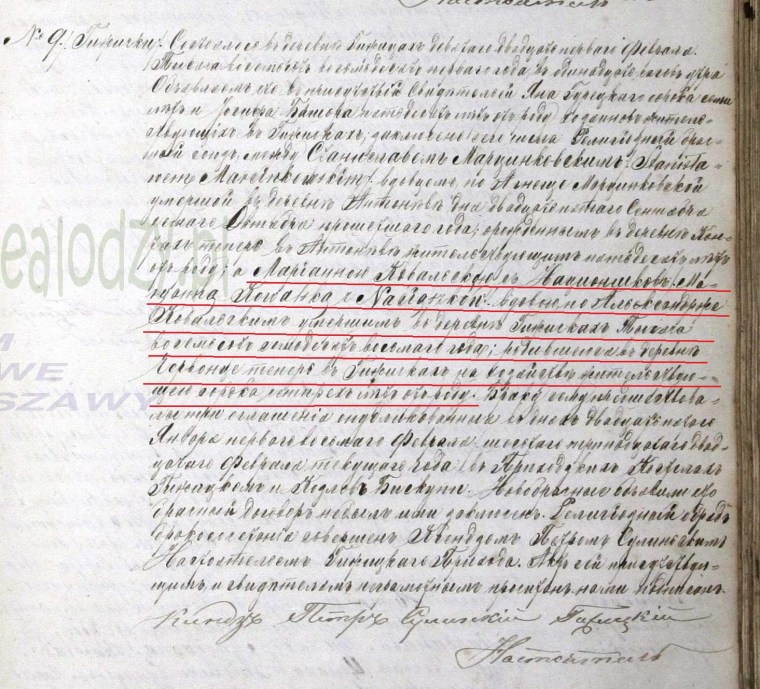

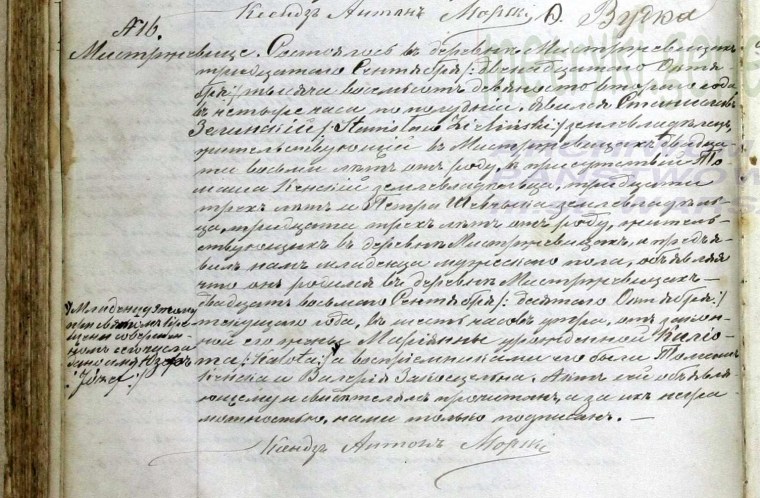

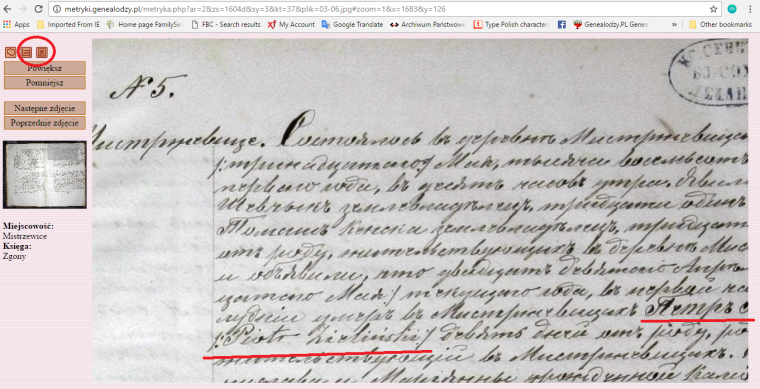

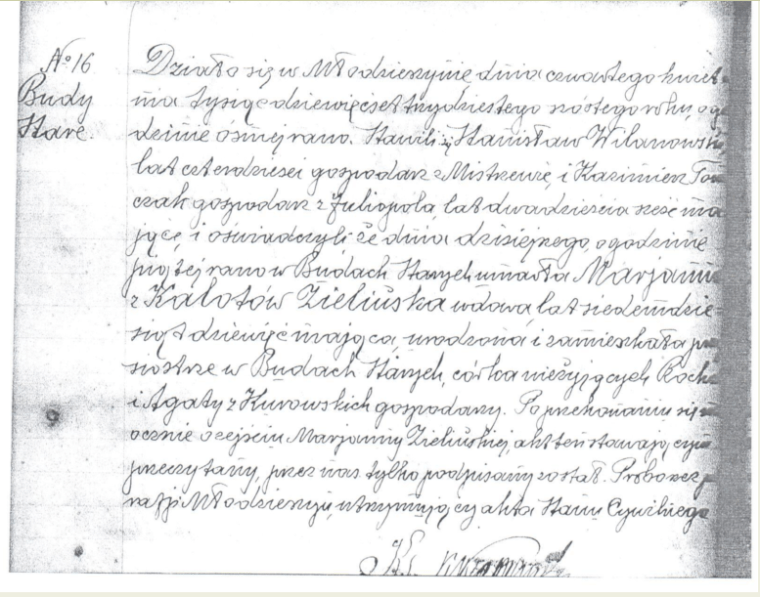

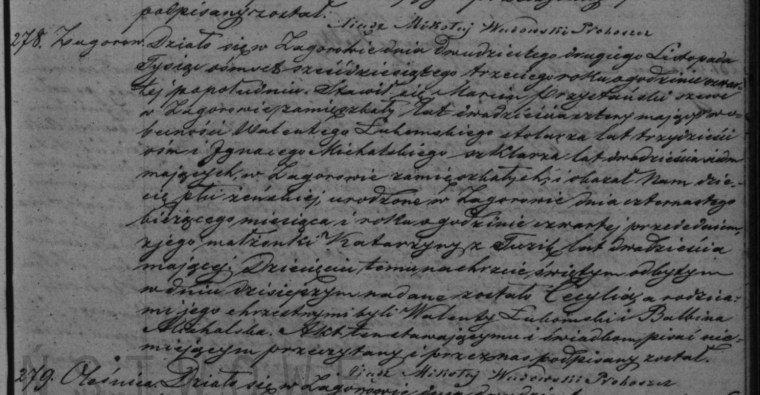

Now we click “skan,” and we’re taken to this screen: In this case, the index entry is linked to a scan within the Metryki database, although some indexes are linked to scans in Szukajwarchiwach or possibly elsewhere. In the middle of the screen, where it says “Pliki” (“Files”), the scans are arranged according to the record numbers they contain. So for example, the scan entitled “01-02” holds death records 1 and 2 from Mistrzewice in 1891. Since Piotr’s death was #5, we want to click on the next file, circled here, which contains deaths 3-6. Clicking on that file takes us to the next screen, which is the scan of the record book itself.

In this case, the index entry is linked to a scan within the Metryki database, although some indexes are linked to scans in Szukajwarchiwach or possibly elsewhere. In the middle of the screen, where it says “Pliki” (“Files”), the scans are arranged according to the record numbers they contain. So for example, the scan entitled “01-02” holds death records 1 and 2 from Mistrzewice in 1891. Since Piotr’s death was #5, we want to click on the next file, circled here, which contains deaths 3-6. Clicking on that file takes us to the next screen, which is the scan of the record book itself.

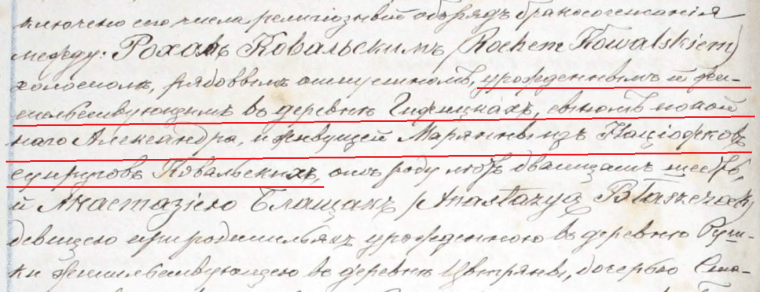

Since Mistrzwice was in Russian Poland and this death occurred after 1868, all records are in Russian. However, as was typical for vital events in this period, names of key participants were written first in Russian, then in Polish, so the viewable portion of the record shown here includes his given name in Russian, Петръ, as well as his full name in Polish, underlined in red. Two useful icons are circled above, on the left in this image: the “ladder” icon takes us back to the preceding page, where we can select a file to view, and the “floppy disk” icon on the right will allow us to download a copy of this image.

Searching Within a Specified Parish

Since we know that my Zieliński family was from Mistrzewice before 1898 when the parish switched, it’s possible to choose to view just the records from that parish by selecting the parish from the drop-down menu below the province name. This is not a new feature, but we now have the additional option of changing the province while keeping all the search parameters the same, instead of having to change the province, then retype all the search parameters. Here is the result of a basic search for “Zielinski” just in the parish of Mistrzewice.

Note that timeline bar that I circled in red. This tells us exactly what marriage records have been indexed for this parish. Although this information was included previously in the “parish” drop-down menu, it’s nice to have the graphic depiction. The bar will change as you select births or deaths if different ranges of years have been indexed for those vital events. It’s very important to pay attention to these ranges of years for indexed records, because more often than not, this explains why we don’t find a particular vital event in Geneteka, even when we know that event took place in a particular parish. In some cases, such as this example for Mistrzewice, all existing records for a parish have been indexed on Geneteka. If a record is not found there, it no longer exists. However, in other cases, the problem is merely that the record has not yet been indexed but is still available if you know where to look.

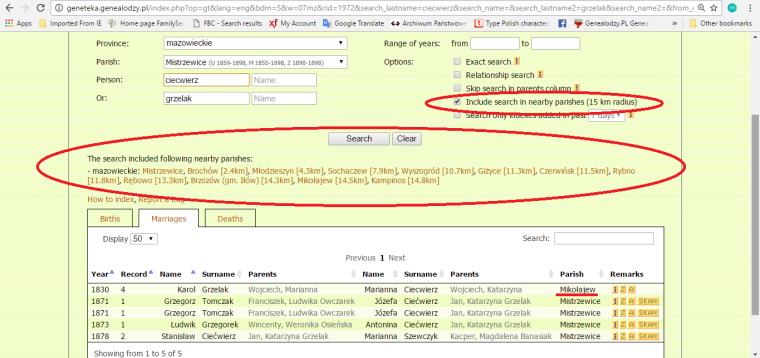

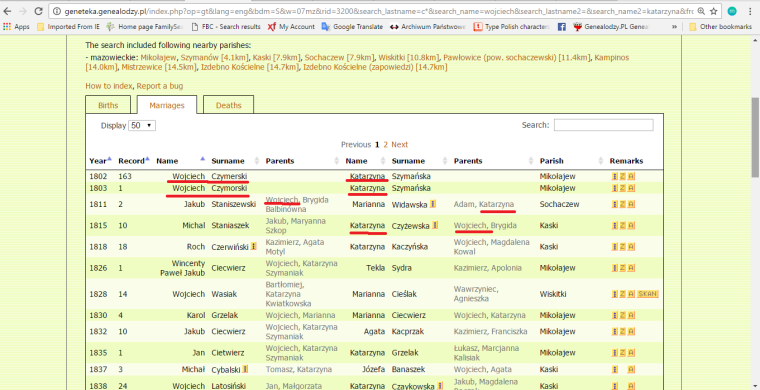

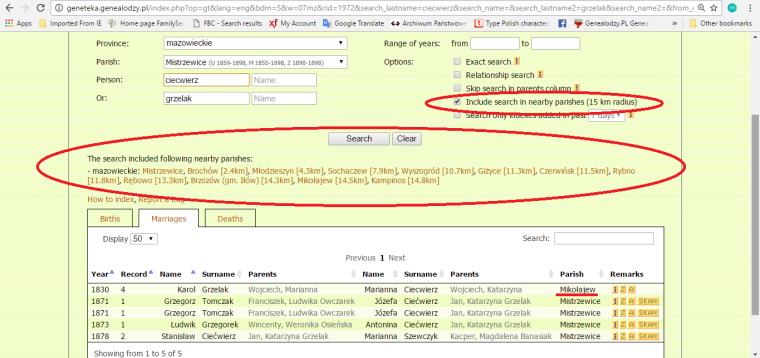

Sometimes it happened that our Polish ancestors moved around a bit within the general area of the ancestral village we originally identified. To address this issue, Geneteka offers the option to include in the search all parishes within 15 km of a selected parish. For example, records from Mistrzewice told me that my great-great-grandmother Antonina (née Ciećwierz) Zielińska was the daughter of Jan Ciećwierz and Katarzyna Grzelak, and that Jan Ciećwierz was the son of Wojciech Ciećwierz and Katarzyna, whose maiden name was not specified. A search of Mistrzewice plus nearby parishes for surnames “Ciecwierz” and “Grzelak” produces four records for my family in Mistrzewice, but also a marriage record for Jan’s sister, Marianna Ciećwierz, to Karol Grzelak in Mikołajew in 1830.

The actual parishes included in this search, as well as their distance from the specified parish, are shown here. Again, remember that there might be additional parishes within a 15 km radius of the target parish, but if they aren’t indexed, they won’t show up here.

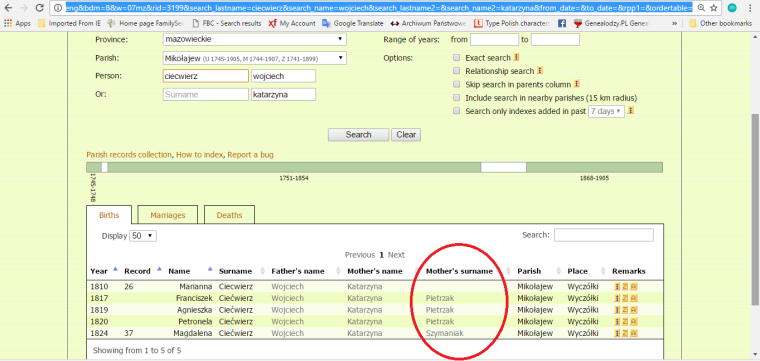

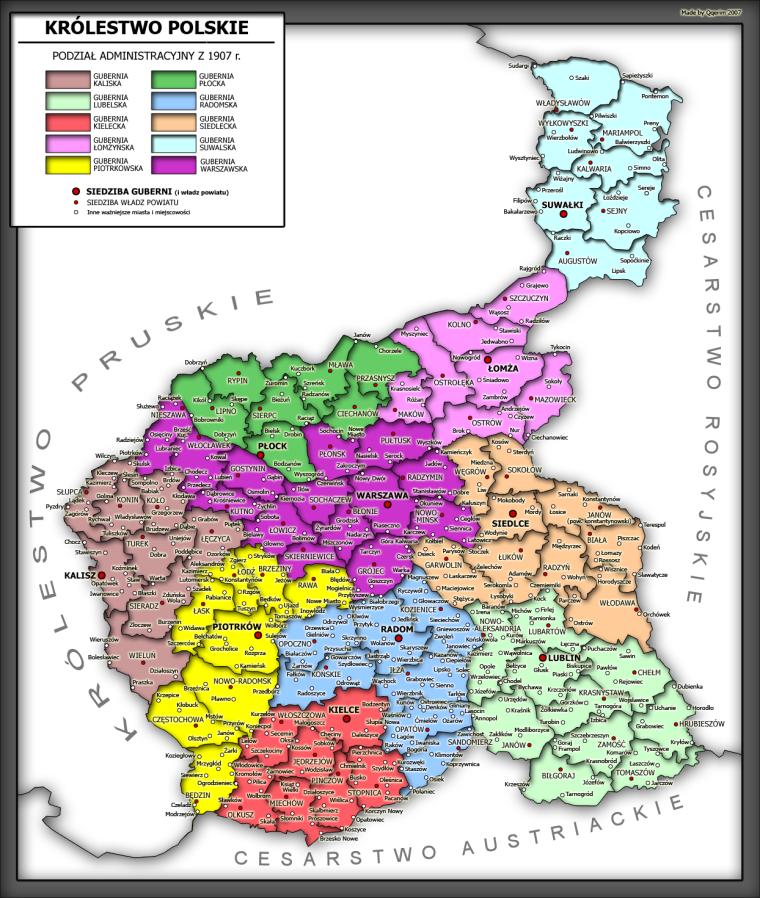

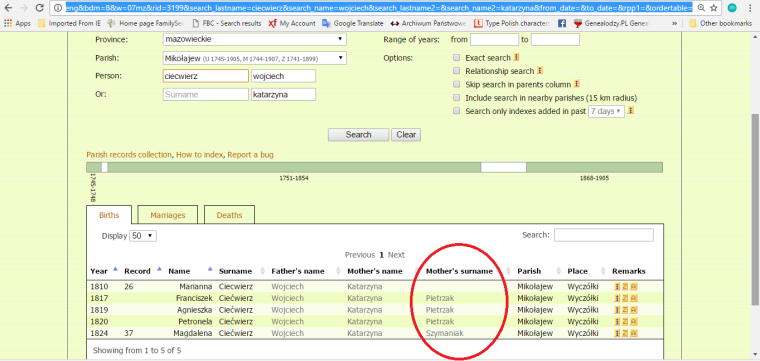

These particular search results illustrate another issue to consider when designing search strategies: the earlier records are less likely to mention a mother’s maiden name. Even if you have a hint of a maiden name from one document or another, it’s better to leave it off and search according to given names. So let’s say we want to follow up now on that hint about Mikołajew and search for children of Wojciech and Katarzyna Ciećwierz. When we search in Mikołajew for children of surname “Ciecwierz” and given name “Wojciech” paired with given name “Katarzyna” we obtain the following:

So far, so good. We have 5 children born between 1810 and 1824, a reasonable range of years, to parents Wojciech and Katarzyna, all born in the village of Wyczółki within the parish of Mikołajew. But we have two different maiden names reported for the mother, Pietrzak and Szymaniak. Hmm…. did Katarzyna Pietrzak die after 1820 and did her husband remarry a woman named Katarzyna Szymaniak before 1824? And where is Jan Ciećwierz, my ancestor, the father of Antonina Zielińska?

The answer to the first question is another story for another day, but the answer to the second question offers a nice opportunity to illustrate another search tool offered by Geneteka, which is wildcard searching. A wildcard is a character that can be used to replace other characters in a search string. Geneteka allows the use of the asterisk (*) to replace one or more characters in a search term. (The use of “?” to replace just one letter is not supported, however.) There are definitely times when it’s advantageous to search this way, but understanding when that is requires a bit of a deeper discussion about Geneteka’s search algorithms.

Geneteka’s Search Algorithms and Wildcard Searches

The indexers at Geneteka are instructed to record surnames as they are written in the record, without making an attempt to standardize them according to modern spelling rules. Consequently certain letter combinations are treated as equivalents, so names with an e/ew, such as Olszeski and Olszewski are equivalent, as are oy/oj names like Woyciechowski/Wojciechowski, and ei/ej names like Szweikowski and Szwejkowski. Similarly, search results include common phonetic substitutions, such as changing “sz” to “ś” such that searching for “Szczygielski” will include results for “Ścigielska,” and “Szcześniak” will include results for “Sciesniak.” Although “ż” is phonetically equivalent to “rz,” Geneteka does not equate “z” with “rz,” because it ignores diacritics so it “sees” z, ź and ż as equivalents. Consequently, names like “Zażycki” and “Zarzycki” need to be searched separately.

Since the original records indexed in Geneteka might be in Polish, Russian, German or Latin, the indexers must be familiar with those languages, and the search engine must be able to handle transliterations between these languages. Therefore we find that the German “ü” is interchangeable with “u”, “fitz” with “fic”, etc. A search on the name “Schmidt,” for example, results in a wide range of phonetic equivalents: Szmit, Schmiedt, Schmit, Szmitt, etc. In addition, the search engine truncates names ending in “e”, “y” or “a,” so searching for Mischke will result in Miszka and Mischka.

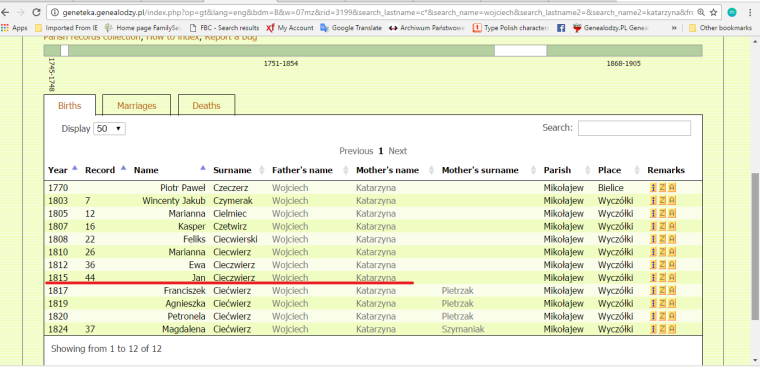

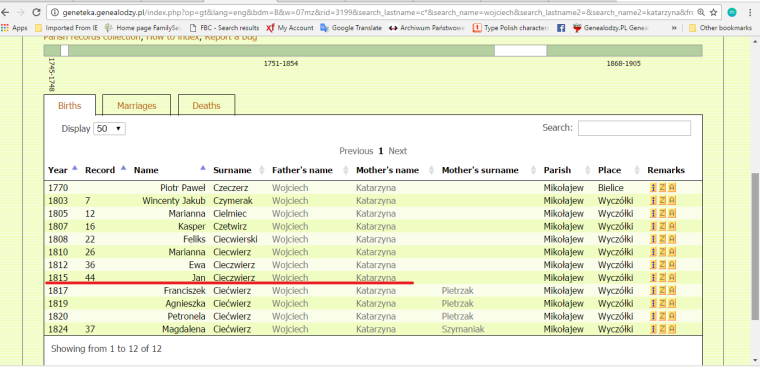

Going back to our present example, this means that Geneteka’s search algorithm automatically equates “Ciecwierz” with “Ciećwierz” and reports results for each, as in the above example. However, some approximate phonetic matches might nonetheless be missed. So if we repeat the search using “C*” instead of “Ciećwierz,” we find my missing ancestor:

Ta da! There’s Jan’s birth in 1815, which fits precisely with the year of birth suggested by his death record from Mistrzewice.

What’s immediately apparent here is how many variant spellings of Ciećwierz and related surnames are not returned by Geneteka’s search algorithm, including Czetwirz, Ciecwierski, Cieczwierz, etc. Additional careful research, including full review of the documents themselves from the diocesan archive in Łowicz, is needed before I can state with confidence which of these records pertain to my family and which don’t. But without doing a wildcard search, I would have missed out on finding many of these.

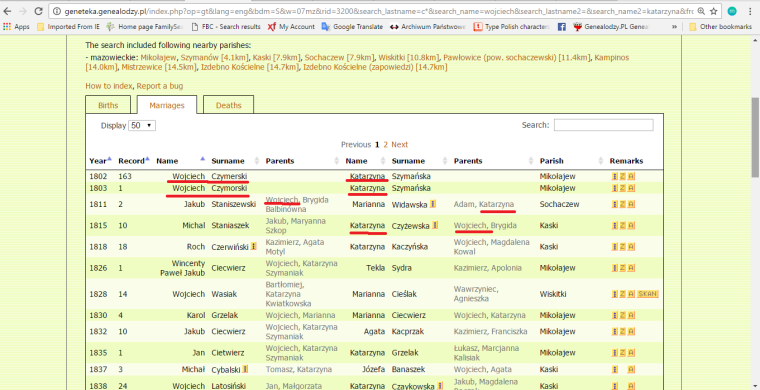

Now suppose I want to find marriages for children of Wojciech and Katarzyna Ciećwierz in Mikołajew or in any of the surrounding (indexed) parishes. If I repeat this search, checking the “search nearby parishes” box, I get the following:

Some of the results returned are marriages for grooms named Wojciech C* and brides named Katarzyna, but results are also returned for marriages in which the groom’s father was Wojciech and the bride’s mother was Katarzyna, or the bride was Katarzyna and her father was Wojciech, etc. — not what we’re looking for. To eliminate these stray hits and help us focus on the results we want, there’s a new feature, “Relationship search/wyszukaj jako para,” which allows us to search using the specified names as a pair. When we repeat this search after checking this box, the results include only those marriages between a groom named Wojciech C* and a bride named Katarzyna, or those marriages for which both Wojciech C* and Katarzyna were named as the parents of either the bride or the groom.

Finally, for those of you who find searching in Geneteka to be addicting, there is a new feature which allows you to search only indexes which have been added recently (past day, 3 days, 7 days, 14 days, or 31 days).

In my case, repeating this search with that box ticked indicates that none of these indexes which include my Ciećwierz ancestors have been added recently, so apparently I’m late to the party, just now tripping over these ancestors who have been waiting here for me, deep within the wonder that is Geneteka.

“Ask not what Geneteka can do for you….”

Hopefully this discussion will give you a better idea of how you can search Geneteka effectively to find your ancestors in Poland. Of course, no discussion of Geneteka can be complete without a final word of gratitude to the volunteer indexers and the PTG, and also an appeal to those of you who find this tool as helpful as I do. If you’re competent with reading vital records in Polish, Russian, German or Latin and want to give back to the genealogical community, please consider volunteering to index records for Geneteka yourself. Most volunteers index records from their own parishes of interest, which is why it’s not possible to submit requests for particular parishes to be indexed. Indexing instructions are provided.. ”

Maybe you don’t feel comfortable with indexing, or don’t have the time? You can still help out by making a donation to the project. Although all the records for both Geneteka and its sister site, Metryki, are indexed or photographed by volunteers, the PTG still must pay for server space to host these online, and those costs add up. If we hope to see this valuable resource remain online and free to everyone, donations are needed, and every little bit helps. Happy hunting!

© Julie Roberts Szczepankiewicz 2017

In this case, the index entry is linked to a scan within the Metryki database, although some indexes are linked to scans in Szukajwarchiwach or possibly elsewhere. In the middle of the screen, where it says “Pliki” (“Files”), the scans are arranged according to the record numbers they contain. So for example, the scan entitled “01-02” holds death records 1 and 2 from Mistrzewice in 1891. Since Piotr’s death was #5, we want to click on the next file, circled here, which contains deaths 3-6. Clicking on that file takes us to the next screen, which is the scan of the record book itself.

In this case, the index entry is linked to a scan within the Metryki database, although some indexes are linked to scans in Szukajwarchiwach or possibly elsewhere. In the middle of the screen, where it says “Pliki” (“Files”), the scans are arranged according to the record numbers they contain. So for example, the scan entitled “01-02” holds death records 1 and 2 from Mistrzewice in 1891. Since Piotr’s death was #5, we want to click on the next file, circled here, which contains deaths 3-6. Clicking on that file takes us to the next screen, which is the scan of the record book itself.