“Aviation in itself is not inherently dangerous. But to an even greater degree than the sea, it is terribly unforgiving of any carelessness, incapacity or neglect.”

— Captain A. G. Lamplugh, British Aviation Insurance Group, London. c. early 1930’s 1

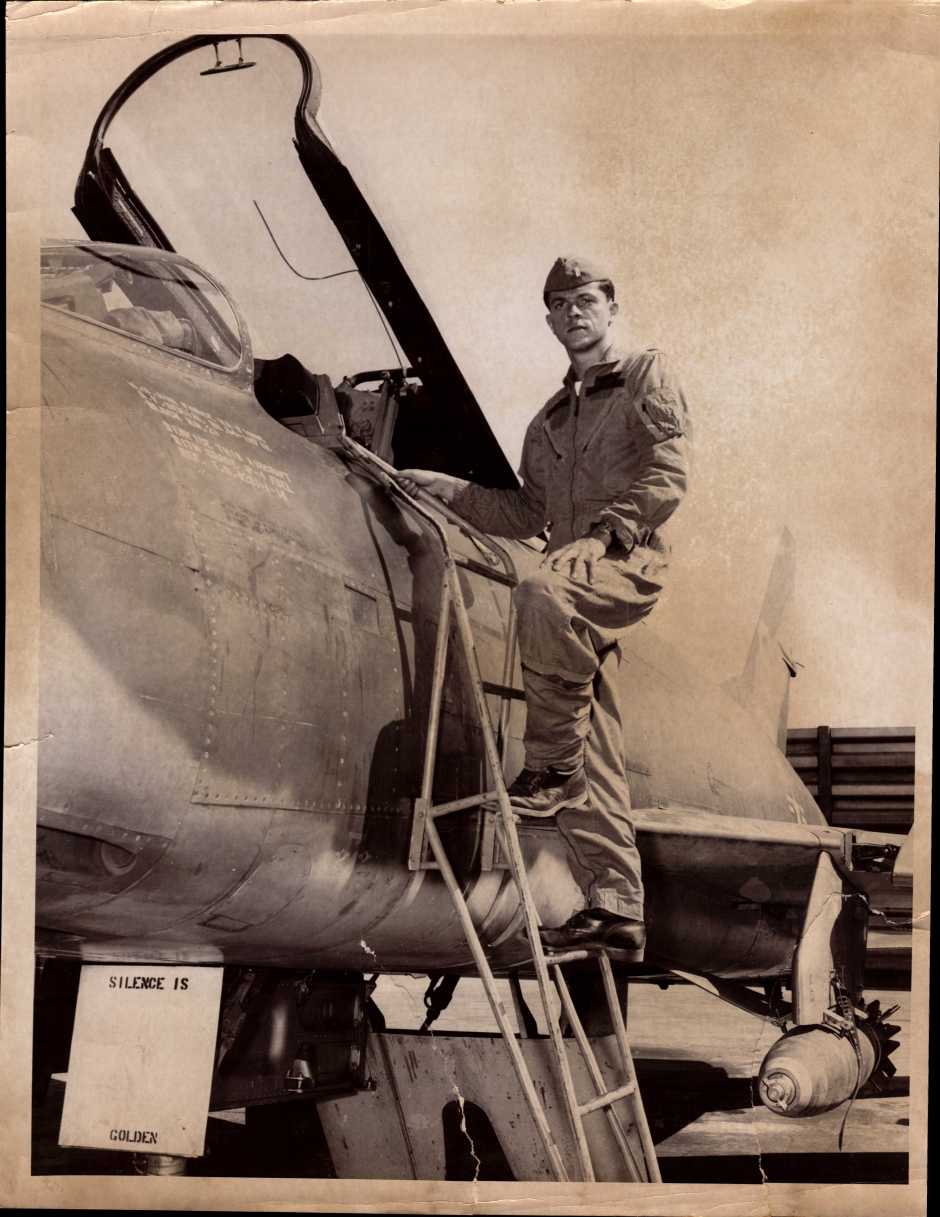

Being a military fighter jet pilot has been such an integral part of my Dad’s life experience that it affects everything he does, did, or ever will do, including the way he parented. My father, Harry W. Roberts, Jr., was sent to Vietnam as the youngest pilot in the 136th Tactical Fighter Squadron just 12 days before I was born, and I didn’t meet him until I was a year old. Dad’s homecoming from the war was something of an adjustment for all of us. Mom jokes that he had no experience with babies or small children, and somehow expected us, his daughters, aged 1 and 2, to shake his hand gravely and say, “How do you do, Father, it’s a pleasure to meet you.” As an Air Force veteran, Dad was all about order and discipline. My bed had to be made with the sheets pulled so smoothly that one could bounce a quarter off of it. I was often told to “shape up or ship out,” and “straighten up and fly right” because “prior planning prevents poor performance.” Hard work, competence, and results were valued and expected. Dad had little patience with people who “didn’t have their s–t together.”

Although I always knew that Dad loved me, he was never comfortable with verbal or physical displays of affection. In all my years of childhood, I can think of maybe two occassions when he kissed me on the forehead after tucking me into bed at night. And my mother tells the story of a time when when my sister and I were about 3 and 4, and she was waiting with us in a checkout line at the grocery store. The gentleman next to her commented on what cute little girls we were, dressed in our matching outfits. He then turned to us and said, “I’ll bet your Daddy calls you his little princesses, doesn’t he?” We smiled and replied happily, “No, he calls us maggots!” Although I don’t remember that particular incident, I do know that it was some time before I realized that “maggot” was not generally accepted as a term of endearment. It seemed affectionate to me, because Daddy always had a hint of a smile when he told us to, “Line up, maggots!”

Dad used to explain that in the Air Force they insisted on discipline because it could save one’s life. In an emergency, there often wasn’t time to think or reason. One had to rely on practiced behaviors and memorized protocols in order to survive. A prime example of this was the time when the engine seized on Dad’s F-100 Super Sabre and Dad had to bail out over the South China Sea. Although I’d heard the story many times when I was growing up, I had a chance to sit down with Dad this past weekend and take notes while he told it again. He also allowed me to scan the transcript of the radio conversation that occurred between him, the control tower, and his flight lead, Lt. Col. Sydney Johnson. (Thanks, Dad!)

The clarity with which Dad remembers that day never ceases to amaze me. It was December 18, 1968. He and three other pilots were headed north from their base in Tuy Hoa on a mission to bomb strategic enemy military targets. Shortly after he took off, he noticed an odd smell inside the cockpit. That in and of itself wasn’t grounds to abort the mission, because sometimes that would happen when the mechanics would change the jet engine oil. However, it was enough to prompt Dad to pay close attention to all the gauges from that time on. The flight continued, and they refueled mid-air without incident, but Dad’s sense that something wasn’t quite right persisted. When they were about 10 minutes from the target, Dad decided to light the afterburner, reasoning that if something bad were about to happen, he’d rather not have it occur when they were right above the target.

Hitting the afterburner is like stepping on the accelerator on a car, and as soon as Dad did that, the plane’s oil pressure plummeted. Dad radioed the rest of the flight and informed them of the situation. Lt. Col. Johnson maneuvered his plane underneath Dad’s and visually inspected the underside of Dad’s F-100. What he saw wasn’t good — bullet holes, with oil pouring out of them. It was later surmised that some Viet Cong sitting offshore in a fishing boat got in a lucky hit with an automatic machine gun as Dad was taking off that morning, causing damage minor enough to be overlooked immediately, but ultimately significant enough to endanger Dad’s life. Lt. Col. Johnson and Dad pulled away from the other two aircraft in the mission at that point. The plan was for the other two pilots to continue to the target while Lt. Col. Johnson escorted Dad back south, where Dad would attempt to land at the base in Da Nang.

There were a couple problems with this plan. First, time was not on their side. The flight manual, which Dad had to memorize as part of his pilot training, stated that once oil pressure is lost, the pilot has between 6-22 minutes before the engine seizes. There was a good chance that they would not make it back to Da Nang. Whether or not he was scared at this point, Dad’s military training kicked in and he was able to perform mechanically and methodically all the necessary procedures that would maximize his chances of landing the plane successfully. The first step was to set the power at 89%, which was the optimized power level that had been determined for that aircraft under these circumstances. Next, he jettisoned all his ordnance and external fuel tanks to make the plane as light as possible, minimize drag, and maximize flying time. Unfortunately, when he hit the “jettison all” button, the left drop fuel tank didn’t disengage completely, and was swaying precariously under the wing. Dad knew that would cause some problems on landing, but there wasn’t much he could do about it at that point.

As the minutes ticked by, Dad disconnected his g-suit from the aircraft and tidied up the cockpit, stowing unnecessary gear. He didn’t want any loose objects to come flying out of the cockpit with him in case he had to eject, since they had the potential to hit him or damage his parachute. However, he knew that luck would play a role as well. A member of his squadron, Capt. Joseph A. “Jake” L’Huillier, had lost his life just a few months earlier after his seat got tangled up with his parachute after ejection from his disabled aircrft.

Exactly 22 minutes after he lost his oil pressure, the jet’s engine started to seize, causing flames to erupt from the tail and nose of the aircraft. Shortly after that the engine stopped completely, while the plane continued to burn. At this point, Dad still had some control of the aircraft, thanks to the Ram Air Turbine (RAT), a device that pops up in the slipstream of the airplane and powers the hydraulics for the flight controls in an emergency, so he could still move the stick. There was only small comfort in this, however. The RAT utilizes ram pressure, caused by the speed of the aircraft, but once landing commences and the aircraft’s speed decreases, the RAT is no longer operative and the stick becomes frozen. Partly because of this factor, no one had ever landed an F-100 with a seized engine successfully. Between that, and the dangling fuel tank under the left wing, Dad realized that landing would have been extremely challenging. Under the circumstances, the growing realization that ejection was unavoidable came as something of a relief.

Established protocol for ejecting from the aircraft specifies that the plane should be at an elevation of approximately 10,000-14,000 feet at the time of ejection, and a speed of 250 knots. Dad spotted two U.S. Navy ships in the distance, so he headed for them in the hope that one of them might pick him up. Immediately prior to ejection, Dad deployed the speed brakes so that the plane would go straight down and not hit anything. When he reached the specified speed and altitude parameters, he ejected from the cockpit.

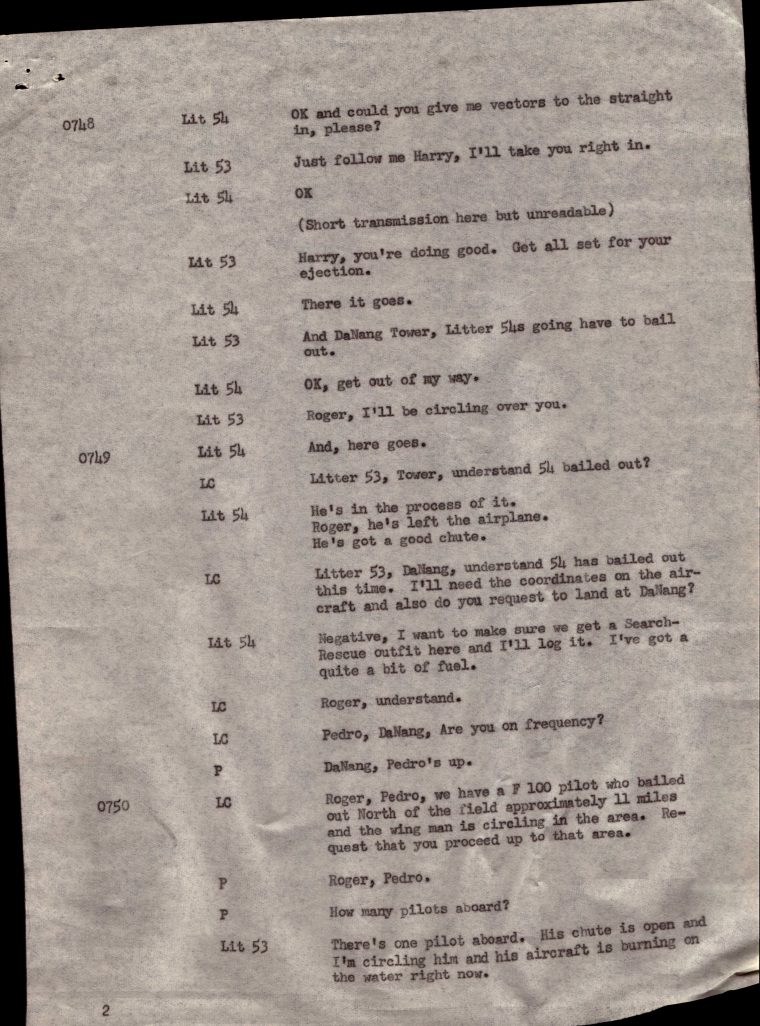

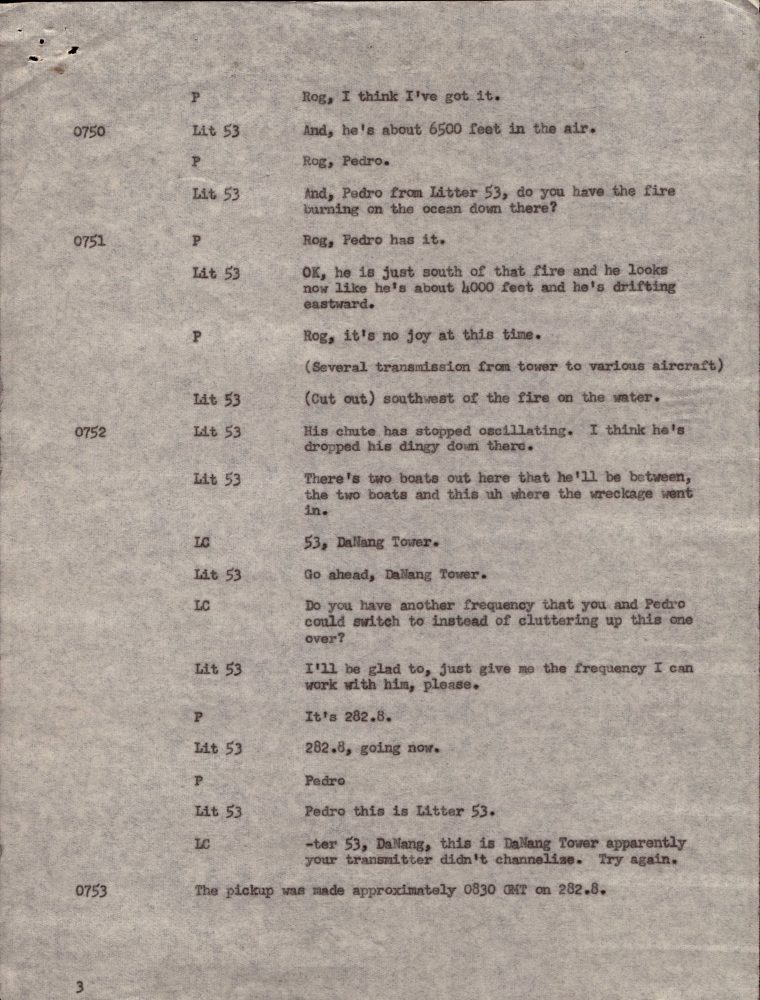

In the following transcript, Dad is Litter 54 (Lit 54), Lt. Col. Sydney Johnson is Litter 53 (Lit 53), LC is the Local Control tower in Da Nang, and Pedro is the search-and-rescue helicopter dispatched from the base in Da Nang.2

Dad recalled that the rationale for heading to the sea was that it was much easier for him to be found and rescued by friendly forces that way, rather than bailing out over the jungle and risking being found by the Viet Cong first. At this point in the transcript, it’s clear that the intent was still for Dad to land the plane. However, things changed very quickly.

Within that same minute, 7:48 am, as the cockpit filled up with smoke, the decision was made to forego the landing attempt and bail out. Note that there appear to be two errors in the second page of the transcript (above). Dad’s final line is “And here goes.” The two quotes after that, which are attributed to Dad, are clearly from Lt. Col. Johnson.

In reading this, I never fail to be impressed by the calm, cool, professionalism of all the servicemen involved. For my family, this was a day that could have meant disaster. For the USAF Air Traffic Control staff in Da Nang, it was just another Wednesday in Vietnam. Notice how they’re anxious for the rescue helicopter, Pedro, and Lt. Col. Johnson to find some other channel for communication, so they don’t tie up the current radio frequency? Although the transcript mentions that “The pickup was made approximately 0830 GMT on 282.8,” it neglects to explain that Dad wasn’t out of the woods once he’d bailed out of his plane. There were still some remaining hazards to negotiate.

Things got off to a good start with the ejection. The seat of the aircraft was designed with a “seat-man separator” function which is intended to ensure that the pilot is clear of the seat before his chute opens. There is a manual override that can be utilized in case this function fails, but by the time Dad had the presence of mind to assess the need for it, he was already separated from the seat and his parachute was successfully deployed. Although Dad was relieved to discover this, he had some new concerns to address. His parachute was equipped with a quick release system underneath a durable cover. The cover was intended to prevent unintentional triggering of the quick release, and Dad realized that the cover on the left side had blown off during the ejection, exposing the mechanism. As a precaution, Dad grabbed onto the left side riser lines of the parachute to be sure that they were secure, and gripped them tightly for the duration of his fall.

The next problem was that the parachute’s design was trapping air, causing him to oscillate back and forth under the chute rather violently, like the clapper in a bell. To remedy this, there were four lines that were identified with red tape that could be cut to stop the oscillation by opening up two panels in the parachute canopy. Dad’s G-suit was equipped with a switchblade knife with a special hook on the end designed for cutting these cords. Needless to say, cutting cords on the parachute which was the only thing standing between him and death took some resolve, and he checked several times to be sure he was cutting the right cords. However, the nauseating effect of the oscillation was enough to persuade him of the necessity of doing it.

The time between ejection and touching down in the South China Sea was perhaps the longest 15 minutes of Dad’s life. It seemed to take forever to fall to earth, to the point that Dad wondered if he were caught in some kind of updraft. He was concerned about disconnecting his parachute as he hit the water. This was necessary to ensure that it didn’t drag him down, or act as a sail, catching the breeze and carrying him over the water at whatever rate the wind was blowing. However, he obviously didn’t want to release the parachute prematurely. After falling for what seemed like a long time, he decided to drop his oxygen mask as a test, and was astonished when he couldn’t even see it hit the water. He was still far too high up. A few more minutes passed and he decided to try again, this time dropping his clipboard. Again, Dad couldn’t even see the splash it made. He resolved to look straight ahead and not think too much about the seemingly slow pace of his descent. He decided that he would release his parachute only when he felt his feet hit the water.

During all this time, Dad’s flight lead, Sydney Johnson, was continuing to monitor his descent. Dad knew Sydney pretty well, and knew that he was an avid videographer. Dad correctly guessed that Sydney was filming the whole episode, flying with the stick between his knees so his hands were free to hold the video camera. Unfortunately, each time Sydney flew past at 500 knots, Dad’s fragile parachute would shudder, threatening collapse. Although Dad smiles when he tells the story now, it’s easy to see how alarming that would have been at the time.

As Dad continued to fall, he prepared for his eventual landing in the water. His survival kit, which was attached to his parachute, contained a raft on a 20-foot lanyard. He inflated the raft, along with his LPUs (Life Preservers Underarm). When Dad’s feet finally made contact with the ocean, he released his parachute which immediately blew away. Still attached to his raft by the lanyard, he swam over to it, climbed inside, and waited for rescue. Overhead he could see the Search-and-Rescue helicopter Pedro, an Army UH-1 helicopter, and the forward air controller‘s plane, along with Sydney Johnson in his F-100, still filming. (When asked why there were so many aircraft, Dad quipped, “It was a slow day for the war.”) He knew he wouldn’t be in the water long, but while he was waiting, Dad began to rummage through his survival kit to see what was in there. He found a saw, which he discarded, and then found some shark repellent tablets, which had already gotten wet and were getting dye everywhere. In those days, shark repellent consisted mainly of a potent dye that turned the water so inky black that the sharks became confused. Dad threw that into the water as well. Finally he found what appeared to be a cellophane-wrapped Rice Krispy bar left over from World War II. He took one bite, but then Pedro began lowering a rescue strop (also known as a “horse collar”) to get Dad out of the water.

During Sea Survival School, Dad had been taught how to be rescued by a helicopter. It wasn’t as straightforward as it might seem. Helicopters can generate a static charge of up to 25,000 volts while flying, which could be transmitted to the rescuee via the horse collar. Therefore it was important to be ground the horse collar by allowing it to contact the water first before touching it, to prevent the delivery of a nasty electric shock. Dad had also been instructed to keep his flight helmet on in case of water rescue. This particular instruction didn’t make sense to Dad until he hit his head on the underside of the helicopter as they attempted to reel him in. When he was finally on board the helicopter, the chief master sergeant took a long look at Dad’s lips and fingers, which were stained blue from handling first the shark repellent and then the Rice Krispy bar. Eventually he asked, “If you don’t mind my asking, Lieutenant, how cold was that water? We’ve picked up guys out of the Arctic who looked better than you!”

One might think that Dad would have earned a little downtime after all of this. However, he was back in the cockpit of a new plane the next day, and Dad would remind us of this fact whenever we were tempted to dwell on some small failure or tragedy. In addition to learning to get back up into that cockpit, Dad learned to be cool under pressure, and to keep his wits about him in a crisis. Although it wasn’t his choice to go to Vietnam, he opted to make the best of a bad situation, turning what would have been a compulsory draft into the Army into an opportunity to learn to fly with the Air National Guard. He sacrificed his own needs and desires and served his country with honor and integrity, working hard amid stress and danger to earn his paycheck to support his family back home. He also managed to keep his sharp sense of humor through it all. Perhaps his military experience made him a sterner, less effusive father than he might otherwise have been. It’s impossible to know what might have been, but I’m proud to be his daughter. I love you, “Daddy Ramjet.”

Sources:

1 English, Dave, Great Aviation Quotes: Safety, Dave English: Aviation Nerd Bon Vivant, http://www.daveenglish.com, accessed 8 February 2017.

2 V.F. Gardner, Major, USAF, Chief, Flight Facilities, Maxwell AFB, Alabama, USA to Lt. Harry W. Roberts, Jr., Tape Transcript, Litter 54, 18 Dec 1968, Vietnam Memorabilia; privately held by Harry W. Roberts, Jr.

The military photos shown here are from the private collection of Harry W. Roberts, Jr. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

© Julie Roberts Szczepankiewicz 2017

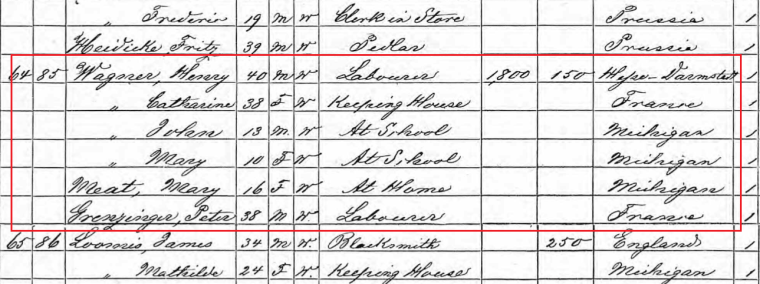

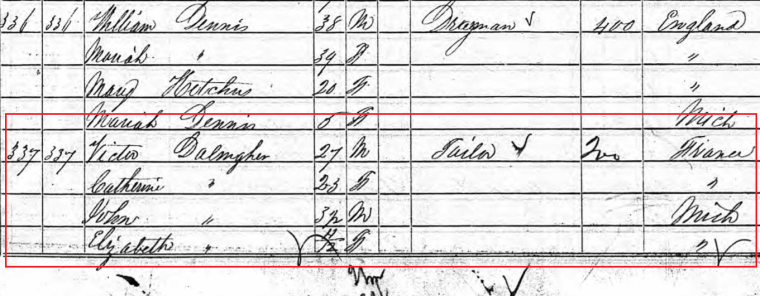

Note that the family includes not only Henry and Catherine and their two children, John and Mary, but also 16-year-old Mary Meat. I haven’t yet figured out how she fits in, so that’s another mystery for another day.

Note that the family includes not only Henry and Catherine and their two children, John and Mary, but also 16-year-old Mary Meat. I haven’t yet figured out how she fits in, so that’s another mystery for another day.

1

1

2

2