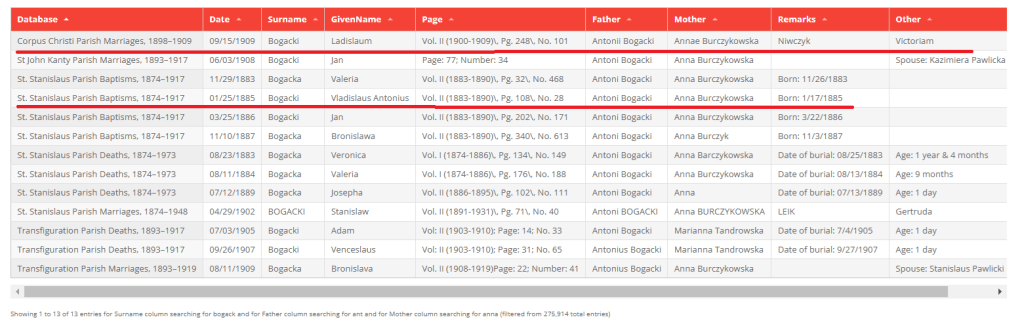

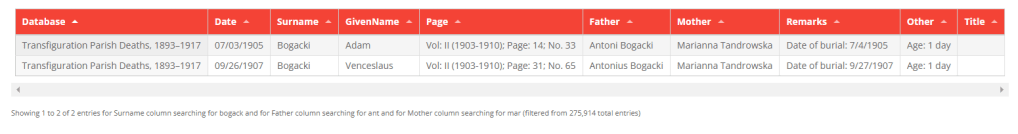

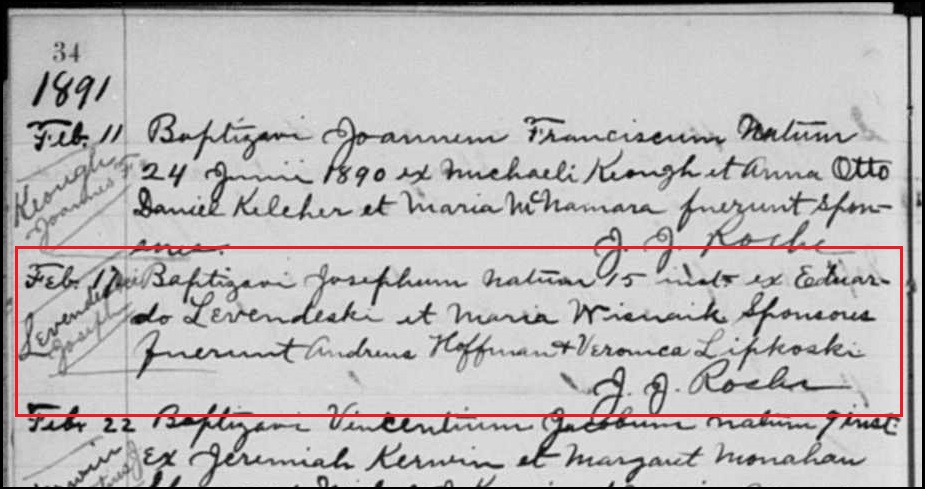

Many of us are familiar with the wonderful information that can be found in Catholic church records. Details such as parents’ names, dates of birth, and place of origin make these records well worth exploring. However, these church records can sometimes introduce mysteries that can only be explained through still deeper research.

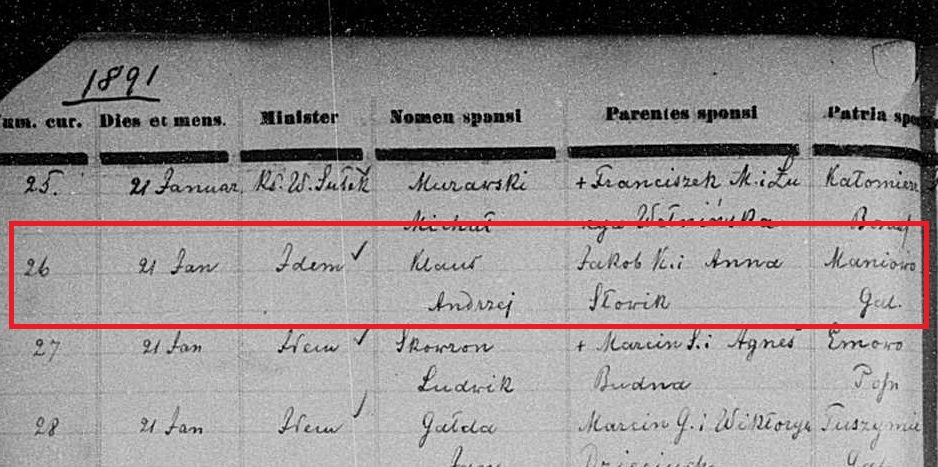

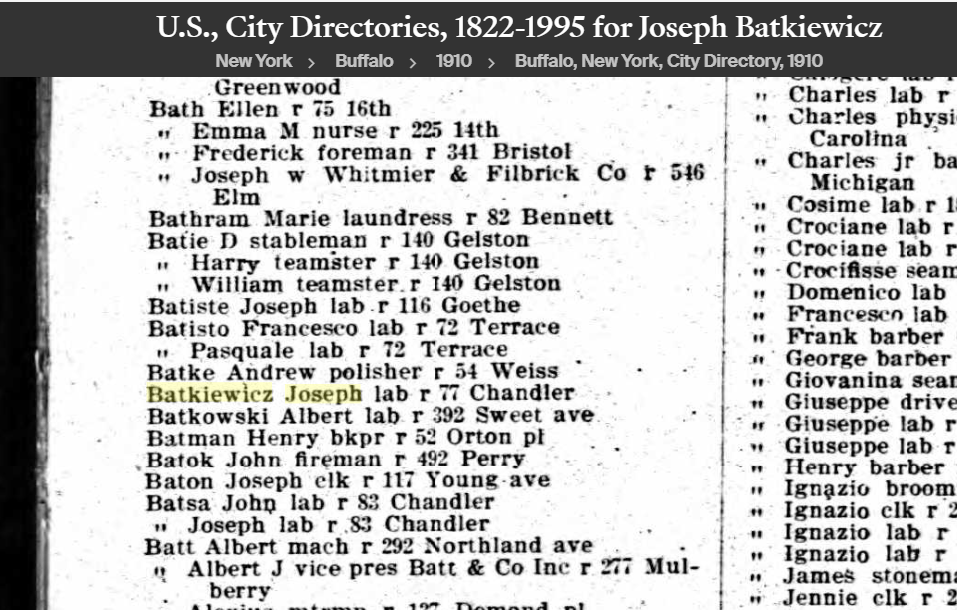

One such mystery involves the marriage records I discovered for my great-great-grandfather, Andrzej Klaus, and his brother, Tomasz, which I discussed in a post back in 2017.[1] At that time, I noted that Andrzej’s mother was identified as Anna Słowik in the record of Andrzej’s marriage to Marianna Łącka, which took place at St. Stanislaus Church in Buffalo on 21 January 1891 (Figure 1).[2]

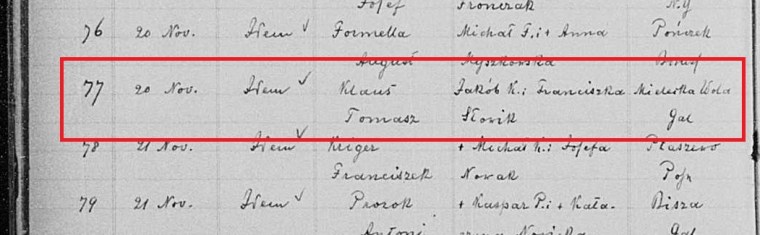

Similarly, when Andrzej’s brother, Tomasz Klaus, married Wiktoria Rak at St. Stanislaus on 20 November 1900, the groom’s mother was identified as Franciszka Słowik (Figure 2).[3]

That’s all well and good, except for the fact that I have good evidence that Andrzej and Tomasz were the sons of Jakub Klaus and Franciszka Liguz. Where does the name Słowik come in? Why did both her sons report this as their mother’s maiden name, why did Andrzej report her given name as Anna, and why am I so certain that her name was really Liguz?

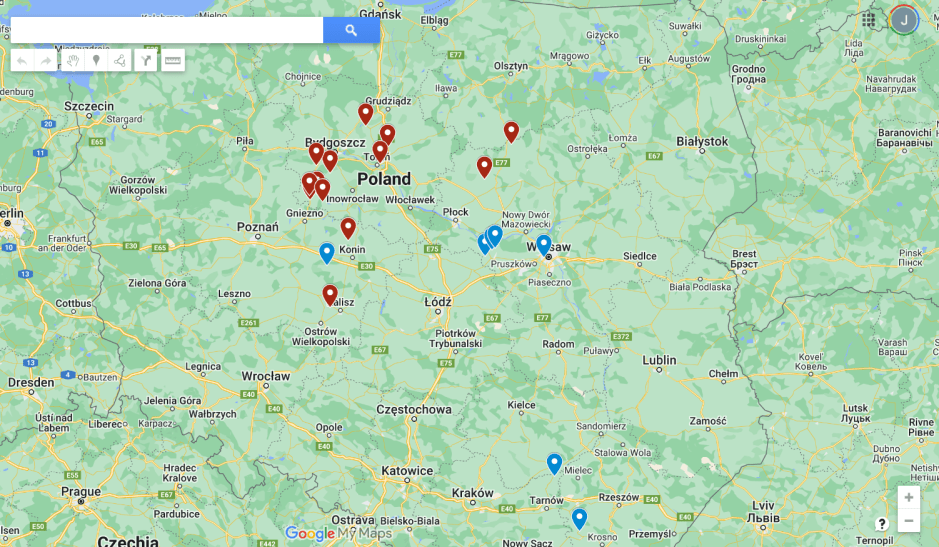

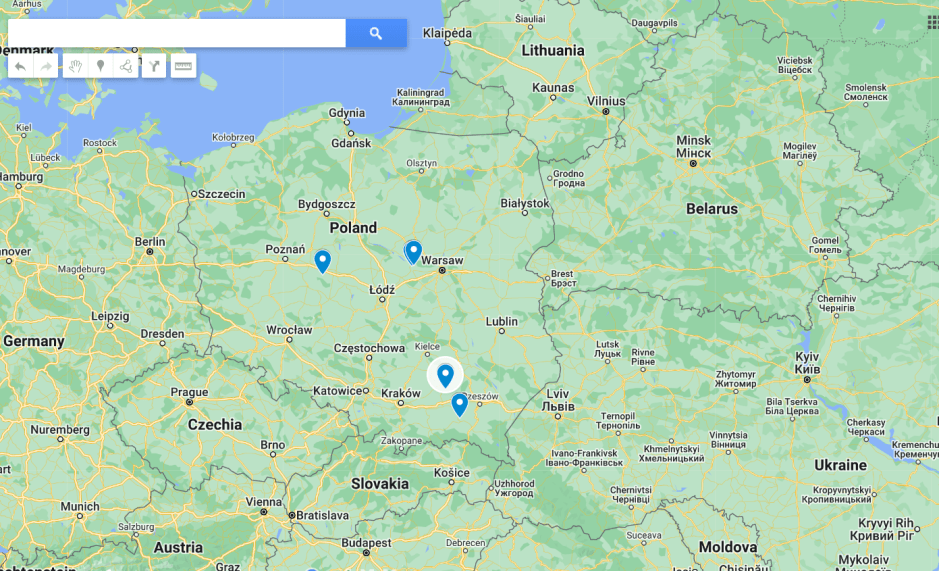

The answers lie in church records created at the parish of St. Mary Magdalene in Szczucin, located in Dąbrowa County, in the Galicia province of the Austrian Empire. This was the parish that served the village of Maniów, where the Klaus family lived. Maniów is presently located in gmina Szczucin, Dąbrowa County, in the Małopolskie province of Poland. In 1981, the village was reassigned to a new parish, Our Lady of Fatima & the Rosary, which was established in the village of Borki. According to local custom, when a village is reassigned to a new parish, the church books for that village are transferred from the old parish to the new parish. So, it was in Borki that I first laid eyes on the books containing the baptismal records for my great-grandfather, Andrzej Klaus, and his siblings, even those those baptisms took place in Szczucin.

Church records revealed that Jakub Klaus and Franciszka Liguz were married on 16 September 1860 in Szczucin (Figure 3).[4]

The Latin marriage record stated that the groom, Jacobus Klaus, was a Catholic, single, 30-year-old servant (famulus), and the son of Laurentius and Anna (née Zolowna) Klaus. Because the records were kept in Latin, Latin forms of given names were used. However, the individuals identified in the records would have been known to their communities by their Polish names, to Laurentius would have been called Wawrzyniec and Jacobus would have been called Jakub. (The name Anna is the same in Latin, Polish, and English.) Note also that the groom’s mother’s maiden name (Zolowna) was given in an old form not used today; the “-ówna” ending signifies an unmarried woman of the Zola family, although her name has also been spelled as Żala and Żola on other records. The bride, 24-year-old Francisca Liguz (Franciszka in Polish), was Catholic, single, and the daughter of Laurentius Liguz and Margaretha (Małgorzata) Warzecha. Witnesses were Adalbertus (Wojciech) Liguz and Joannes (Jan) Mamuśka.

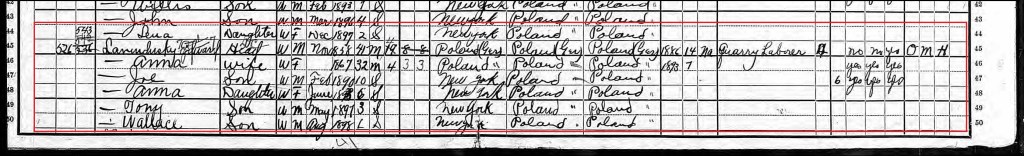

Baptismal records identified eight children born to this couple:

- Jan Klaus, born 09 October 1860 in Maniów,[5] died 13 May 1920 in Plymouth, Luzerne, Pennsylvania, USA;[6]

- Józef Klaus, born 26 February 1863 in Maniów,[7] died 12 January 1874 in Wola Mielecka;[8]

- Andrzej Klaus, born 25 November 1865 in Maniów,[9] died 14 June 1914 in North Tonawanda, Niagara, New York, USA;[10]

- Michał Klaus, born 01 September 1867 in Maniów,[11] no death or marriage record yet discovered;

- Paweł Klaus, born 28 May 1870 in Maniów,[12] died 14 March 1879 in Wola Mielecka;[13]

- Piotr Klaus, born 28 May 1870 in Maniów,[14] died 22 July 1870 in Maniów;[15]

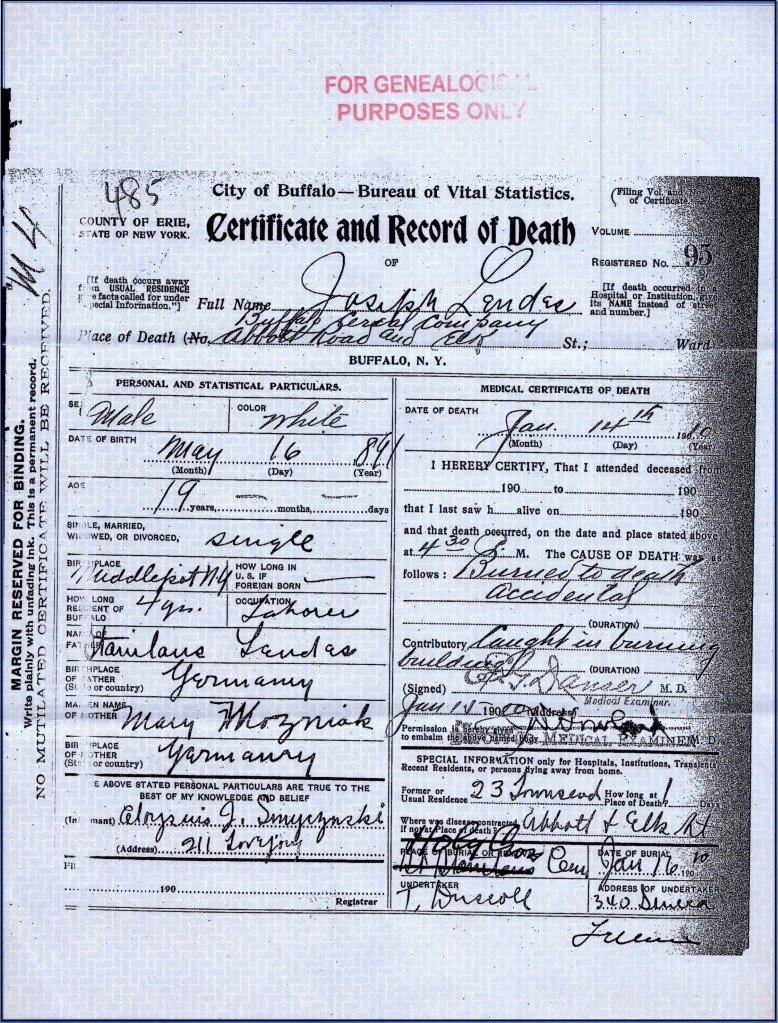

- Tomasz Klaus, born 03 September 1872 in Wola Mielecka,[16] died 28 December 1911 in Buffalo, Erie, New York, USA;[17]

- Helena Klaus, born 25 September 1875 in Wola Mielecka,[18] died 15 August 1878 in Wola Mielecka.[19]

Baptismal records from Galicia typically identify not only the parents of the child, but also the grandparents, the baptismal records for Andrzej Klaus and each of his siblings identified their mother as Francisca, daughter of Laurentius Liguz and Margaretha Warzecha.

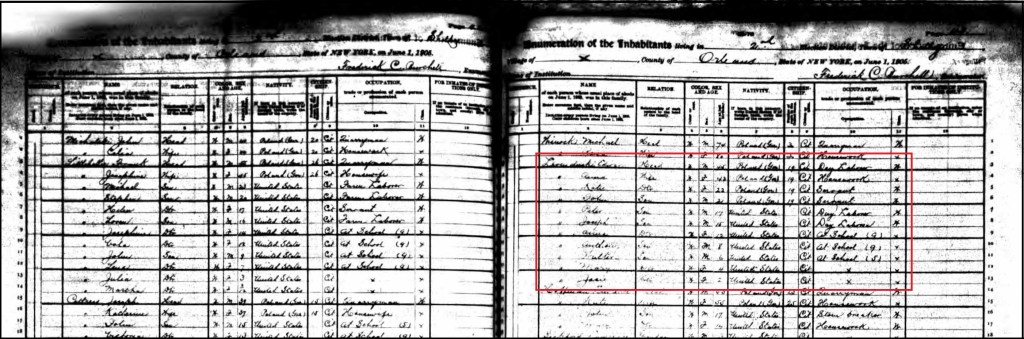

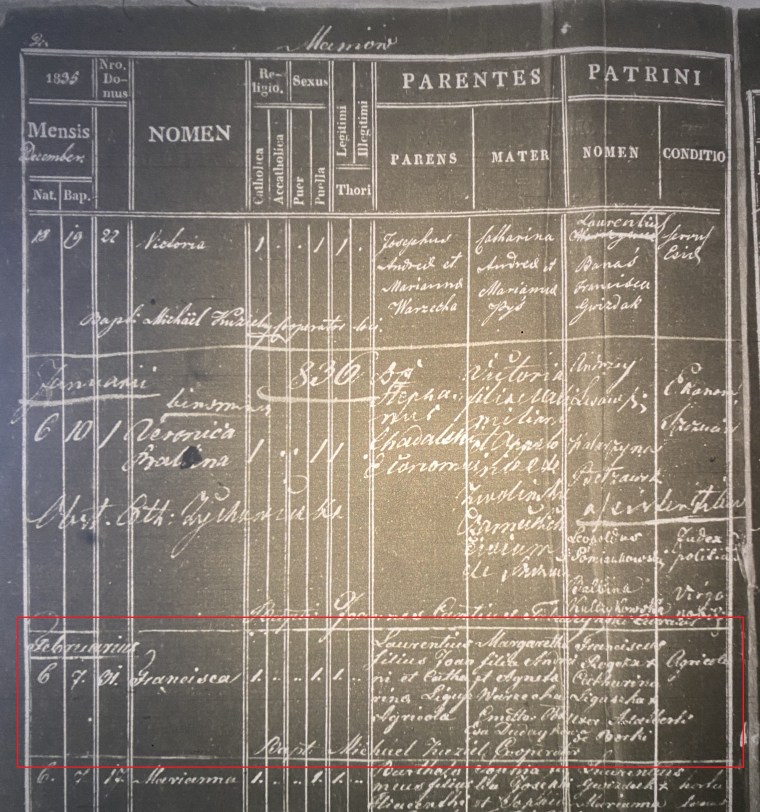

Franciszka Liguz herself was born 6 February 1836 in Maniów, the oldest child of Wawrzyniec and Małgorzata (Warzecha) Liguz (Figure 4) .[20]

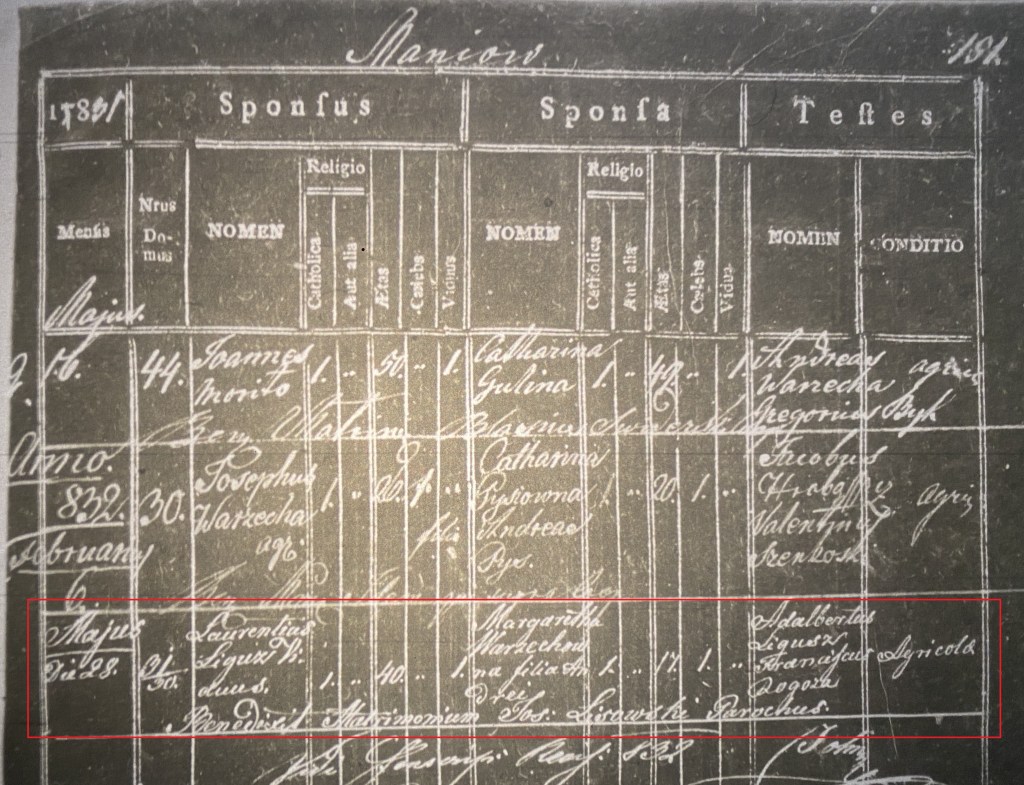

Her birth record identified her parents as Laurentius, son of Joannes and Catharina Liguz, and Margaretha, daughter of Andreas and Agnes Warzecha. Wawrzyniec/Laurentius Liguz and Małgorzata/Margaretha Warzecha were married on 28 May 1832 in Szczucin (Figure 5).[21] The marriage record identified Wawrzyniec as a 40-year-old widower, while the bride was just 17 years old. Parents’ names were not reported for Wawrzyniec, but Małgorzata’s father was named Andreas/Andrzej, consistent with the information reported on Franciszka Liguz’s birth record.

Wawrzyniec and Małgorzata had six children together:

- Franciszka, born 06 February 1836 in Maniów,[22] date of death unknown;

- Józefa Zofia Liguz, born 11 January 1838 in Maniów,[23] date of death unknown;

- Jan Liguz, born 01 January 1840 in Maniów,[24] died 4 January 1840;[25]

- Sebastian Liguz, born 01 Janaury 1840 in Maniów, [26] died 2 January 1840;[27]

- Jan Liguz, born 13 June 1841 in Maniów,[28] died 8 September 1841;[29]

- Józef Liguz, born 2 March 1844 in Maniów,[30] died 16 May 1846.[31]

The twins, Jan and Sebastian, both died within a few days of birth, and the younger son named Jan, born in 1841, died at the age of 3 months. Wawrzyniec Liguz died at the age of 55 on 6 November 1845, leaving Małgorzata as a 30-year-old widow with three children, ages 9, 7, and 20 months.

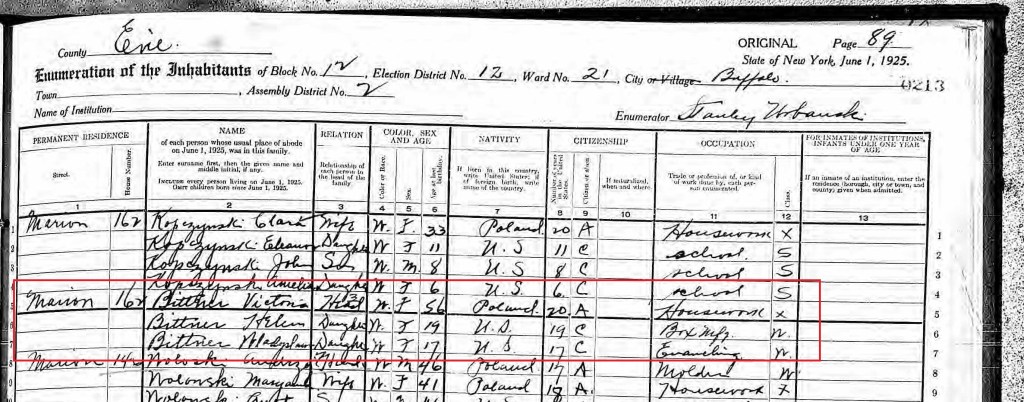

How Małgorzata supported her young family during the next three years is unclear. Church records described her late husband, Wawrzyniec, as a “hortulanus,” which was a peasant with a small, garden-sized plot of land.[32] They were residents of house number 31 in Maniów, but she was living at house number 40 at the time of her second marriage to Jan Podkówka, on 1 November 1848 in Szczucin, suggesting that she may have moved in with other family members after her husband’s death.[33]

Jan Podkówka was a 50-year-old father and widower when he married Małgorzata Liguz. The couple had two children together:

- Tomasz Podkówka, born 5 November 1849,[34] died 16 November 1873;[35]

- Agata Podkówka, born 1 February 1852,[36] died 6 March 1910.[37]

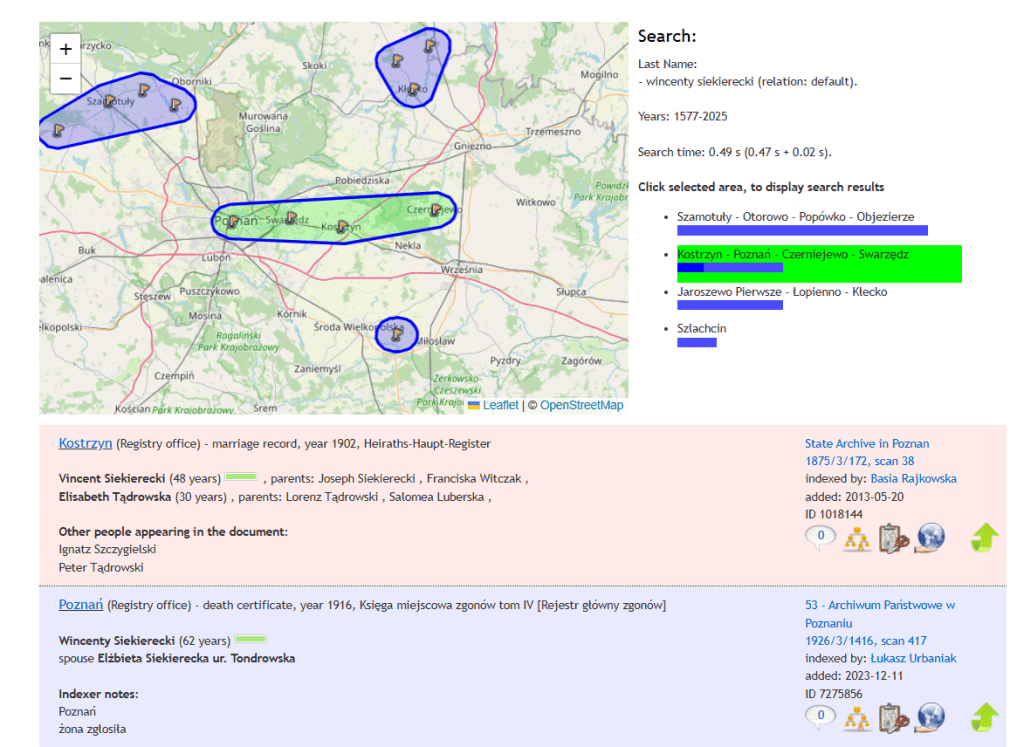

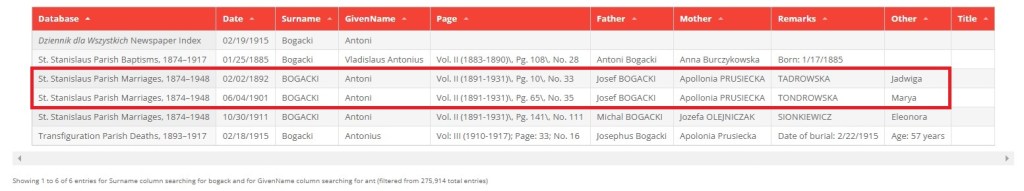

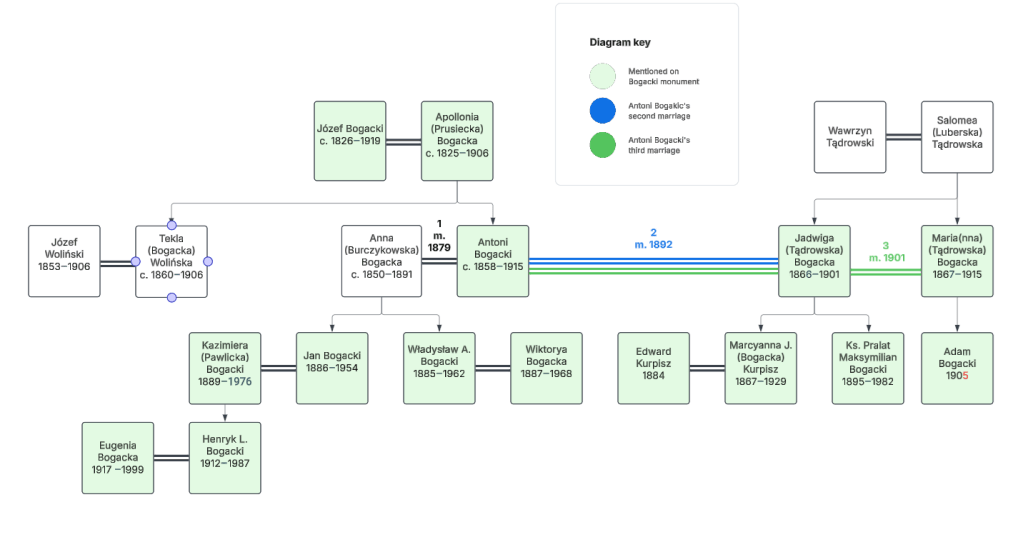

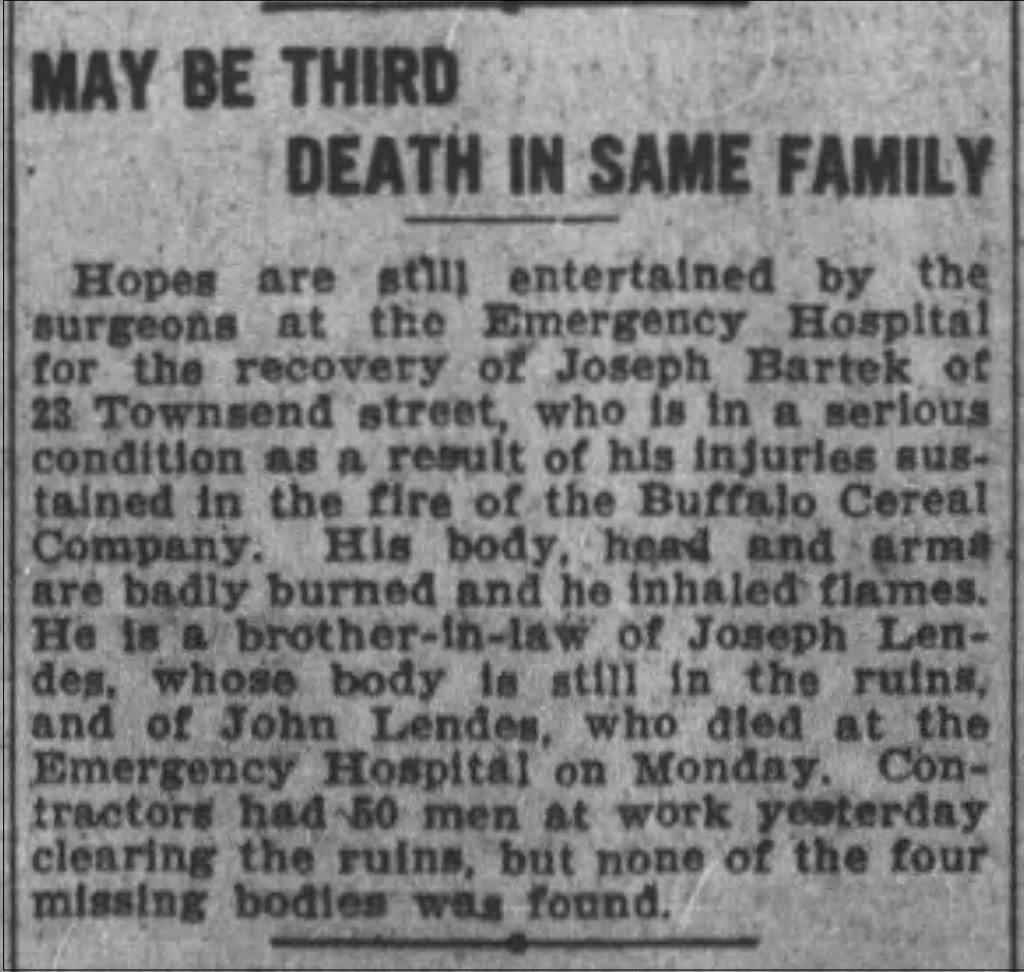

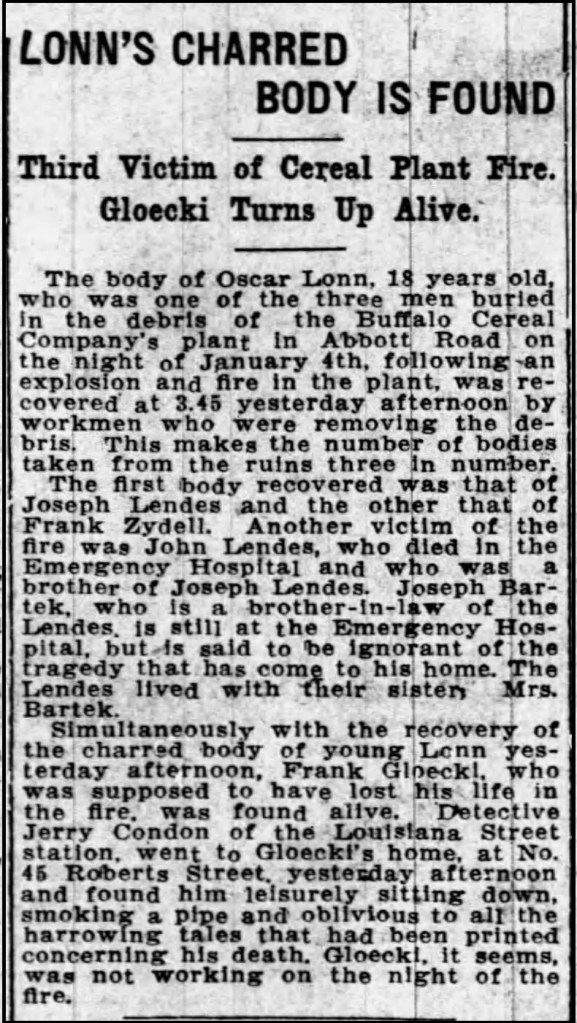

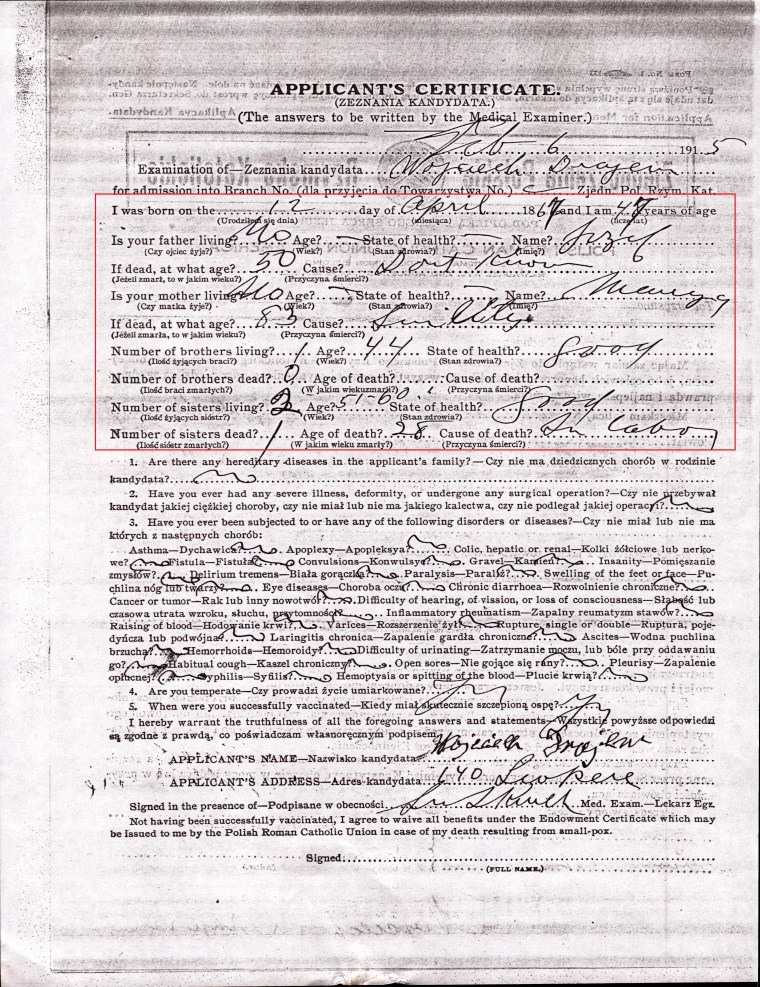

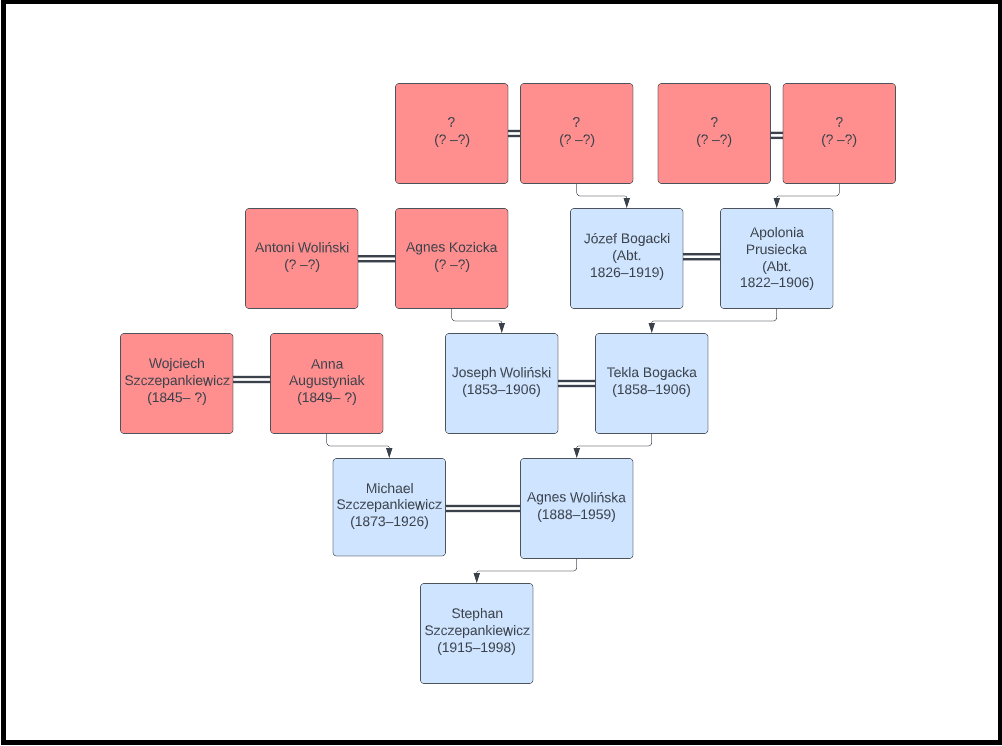

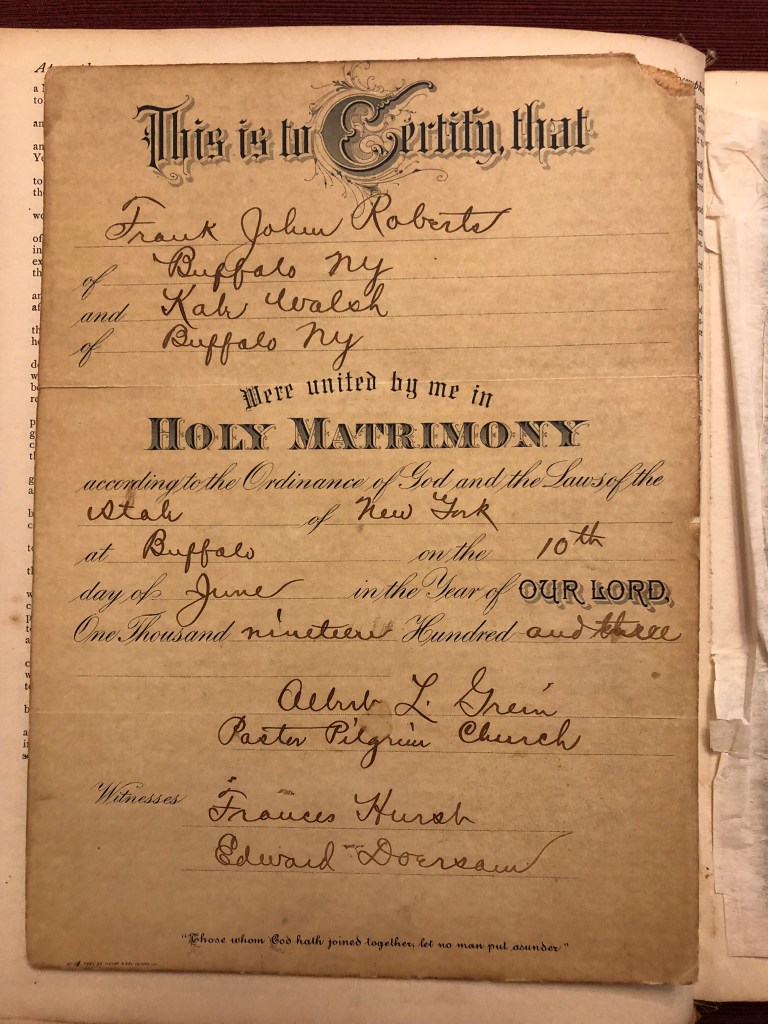

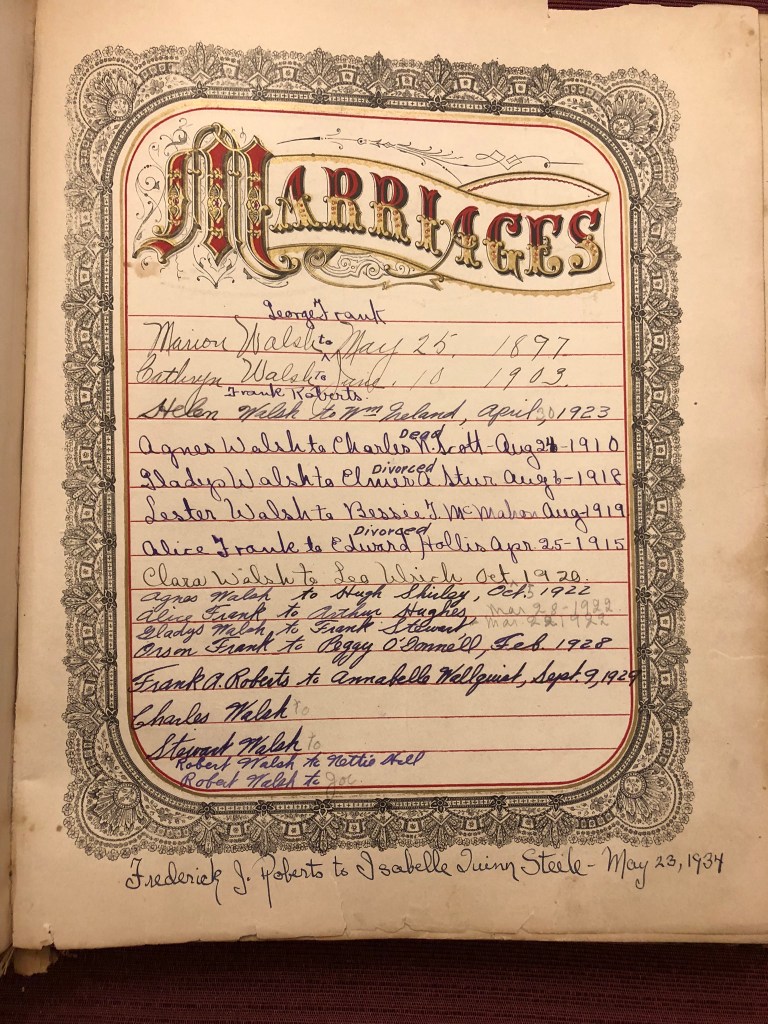

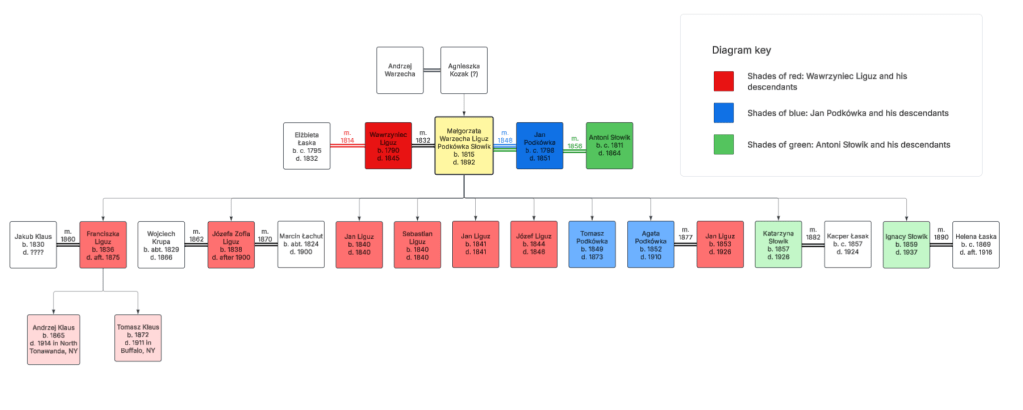

Jan Podkówka must have died before 27 January 1856,[38] because that was when Małgorzata married a third time, to another widower, Antoni Słowik.[39] Here, at last, is the answer to the mystery found in the Buffalo church records regarding the identification of Andrzej and Tomasz Klaus’s mother as Słowik rather than Liguz. Figure 6 shows a simplified version of Małgorzata’s family tree.

At the time of her marriage to Antoni Słowik, Małgorzata was a 41-year-old mother of eight children, four of whom were still alive. Franciszka Liguz and Józefa Zofia Liguz were ages 20 and 18, respectively, while Tomasz Podkówka and Agata Podkówka were 7 and nearly 4 years old, respectively. Antoni and Małgorzata had two children together prior to his death on 4 April 1864:[40]

- Katarzyna Słowik, born 14 February 1857 in Borki,[41] died 25 April 1902 in Delastowice;[42]

- Ignacy Słowik, born 28 July 1859 in Borki,[43] died 5 October 1937 in Maniów.[44]

It’s unclear why Andrzej and Tomasz Klaus would have reported their mother’s maiden name as Słowik rather than Liguz, and why Andrzej would have reported her given name as Anna, rather than Franciszka. It may have been a simple misunderstanding of the question, providing her name at the time of their marriages, rather than her maiden name. It’s also possible that an error was introduced during recopying of the church books from St. Stanislaus in Buffalo; the fact that all the church records from St. Stanislaus appear to be in the same handwriting suggests that these are not original records.

Widowed for the third time at the age of 49, Małgorzata never remarried after Antoni’s death in 1864. Her oldest child, Franciszka, had been married for four years by the time her stepfather, Antoni Słowik, died. Małgorzata’s second child, Józefa Zofia (known as Zofia), had married Wojciech Krupa on 27 July 1862, so she, too, was living independently.[45] Tomasz Podkówka, age 14, was old enough to be a help to his mother, along with his younger sister, Agata Podkówka, age 12. Katarzyna and Ignacy Słowik were only 7 and 5 when their father died, and once again, it’s unclear how Małgorzata managed to support her family following her husband’s death, although it’s probable that she relied on assistance from additional family members.

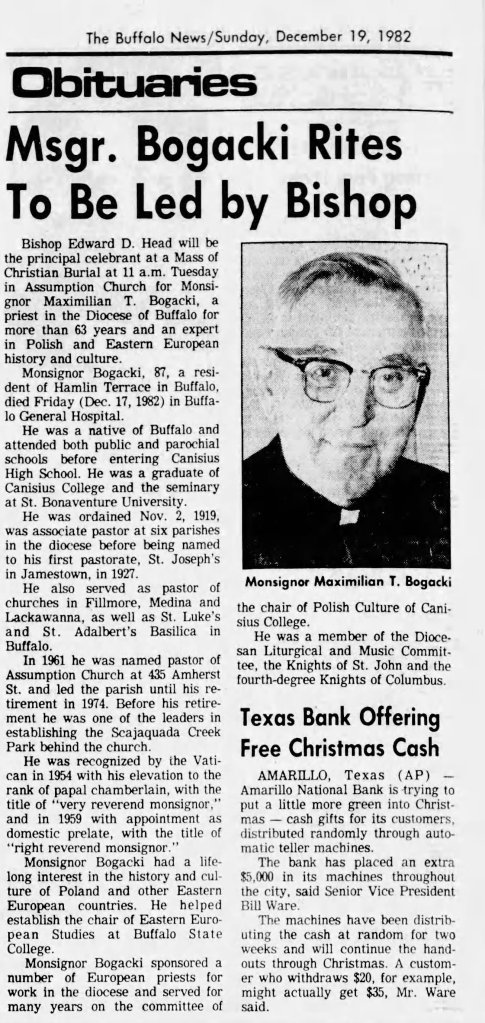

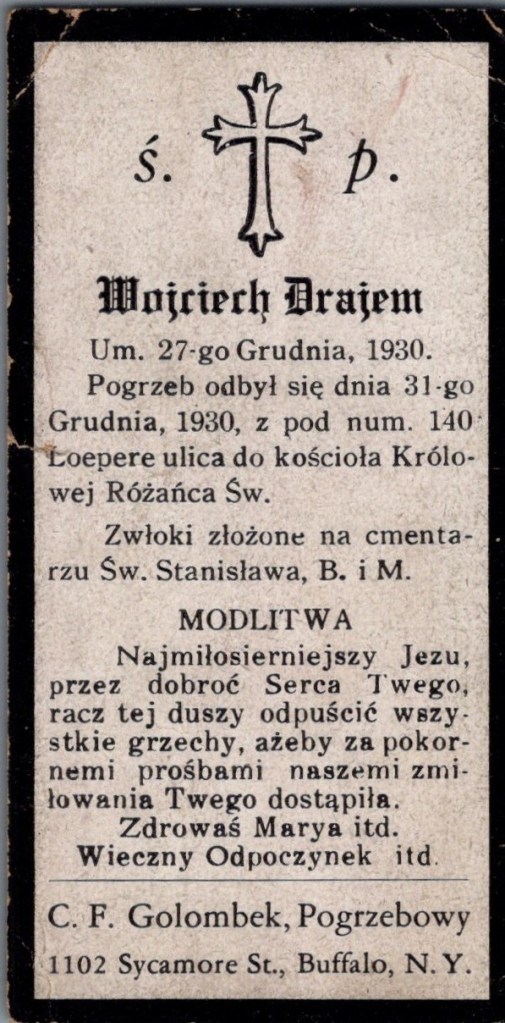

Małgorzata Warzecha Liguz Podkówka Słowik died at the age of almost 77 on 7 January 1892, having outlived all three husbands, and five of her ten children.[46] Her death record, shown in Figure 7, identified each of her previous husbands. At the time of her death, Małgorzata was living in house number 33 in Borki, and further research may identify the owner of that home.

Researching Małgorzata’s life revealed more than just names and dates—it uncovered a narrative of resilience, adaptation, and change. Her multiple marriages and the resulting blended family echo the complex structures many genealogists discover in their own research. Many questions still remain, but this is the nature of genealogical research; our ancestors left behind breadcrumbs, not roadmaps, and it’s up to us to piece together their stories with patience and persistence.

© Julie Roberts Szczepankiewicz 2025

[1] Julie R. Szczepankiewicz, “And the Walls Came Tumbling Down: New Discoveries in My Klaus Family Research, Part I,” From Shepherds and Shoemakers (https://fromshepherdsandshoemakers.com/), published 8 August 2017, accessed 12 March 2025.

[2] Roman Catholic of St. Stanislaus, Bishop & Martyr (Buffalo, Erie, New York, USA), Marriages, Vol. II (1891-1931), p. 1, 1891, no. 26, Klaus-Łączka, 21 January 1891; digital image, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4N-64SL-7?i=1407&cat=23415 : accessed 15 March 2025).

[3] Ibid., p. 62, 1900, no. 77, Klaus-Rak, 20 November 1900; digital image, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4N-64QV-L?i=1468&cat=23415&lang=en : accessed 8 August 2017).

[4] Roman Catholic Church of St. Mary Magdalene (Szczucin, Dąbrowa, Małopolskie, Poland), Maniów, Akta małżeństw [Marriage records], 1860, 16 September, Klaus-Liguz; FamilySearch Library, film no. 1958428 Items 7-8.

[5] Roman Catholic Church, Sanktuarium Matki Bożej Fatimskiej – Różańcowej (Borki, Szczucin, Dąbrowa, Małopolska, Poland), Baptisms, 1860, no. 20, Joannes Klaus; parish archive. Mother was recorded as “Francisca nata Laurentio Liguz et Margaretha Warzecha.”

[6] Pennsylvania, USA, Death Certificates, 1920, no. 60801, John Klaus, died 13 May 1920; imaged as, “Pennsylvania Death Certificates, 1906-1966,” database, Ancestry, (http://ancestry.com : 13 March 2025).

[7] Roman Catholic Church, Sanktuarium Matki Bożej Fatimskiej – Różańcowej (Borki, Szczucin, Dąbrowa, Małopolska, Poland), Baptisms, 1863, unnumbered entries in chronological order, Josephus Klaus, born 26 February 1863. Mother was recorded as “Francisca nata Laurentio Liguz et Margaretha Warzecha.”

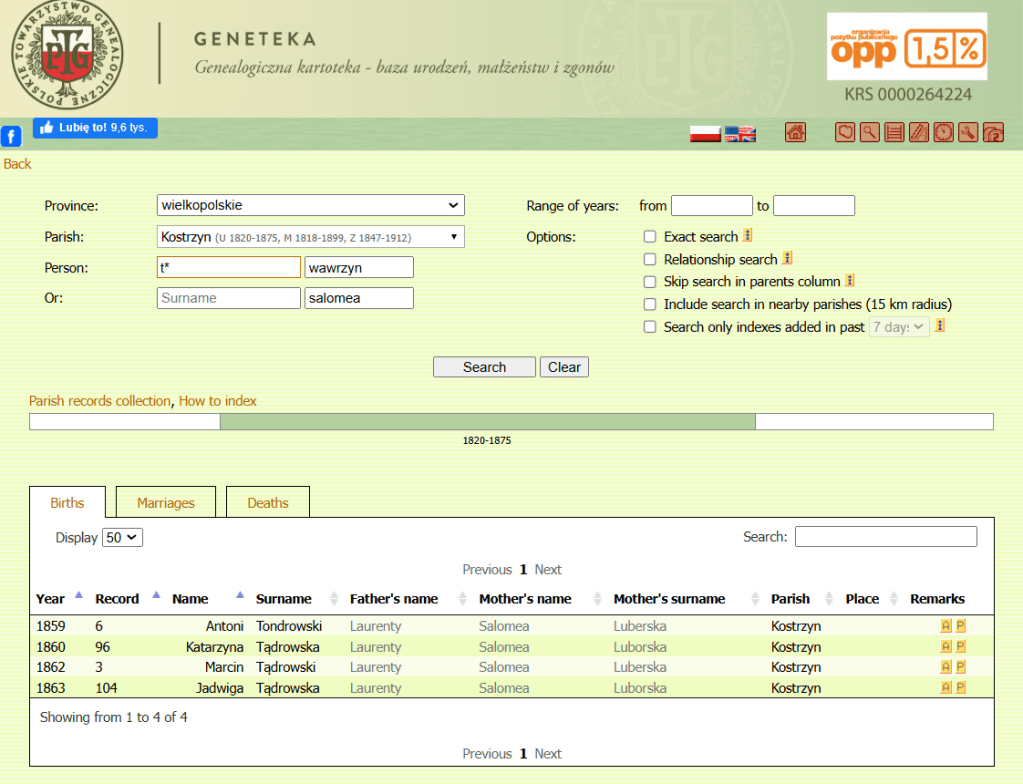

[8] Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne [Polish Genealogical Society], Geneteka, database (https://geneteka.genealodzy.pl/ : accessed 15 March 2025), search result for Klaus deaths in Podkarpackie, 1874, no.4, Józef Klaus, son of Jakub Klaus and Franciszka Liguz, parish Książnice-Wola Mielecka, died in Wola Mielecka on 12 January 1874 at the age of 7 years, source: parish archives, indexed by Krzysztof Gruszka.

[9] Roman Catholic Church, Sanktuarium Matki Bożej Fatimskiej – Różańcowej (Borki, Szczucin, Dąbrowa, Małopolska, Poland), Baptisms, 1865, no. 37, Andreas Klaus, born 25 November 1865. Mother was recorded as “Francisca nata Liguz fil: Laurentii et Margarethae natae Warzecha.”

[10] North Tonawanda City Clerk (North Tonawanda, Niagara, New York, USA), Death Certificates, 1914, no. 82, Andro Klaus, 14 June 1914.

[11] Roman Catholic Church, Sanktuarium Matki Bożej Fatimskiej – Różańcowej (Borki, Szczucin, Dąbrowa, Małopolska, Poland), Baptisms, 1867, no. 20, Michael Klaus, born 1 September 1867. Mother was recorded as “Francisca nata Liguz fil. Laurentii et Margarethae natae Warzecha.”

[12] Ibid., 1870, no.18, gemini, Paulus, Petrus Klaus, born 28 May 1870. Mother was recorded as “Francisca filia Laurentii Liguz et Margaritha Warzecha.”

[13] Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne [Polish Genealogical Society], Geneteka, database (https://geneteka.genealodzy.pl/ : accessed 13 March 2025), search result for Klaus deaths in Podkarpackie, 1879, no. 7, Paweł Klaus, son of Jakub Klaus and Franciszka Liguz, parish Książnice-Wola Mielecka, died in Wola Mielecka on 14 March 1879 at the age of 8 years, source: parish archives, indexed by Krzysztof Gruszka.

[14] See note 12.

[15] Ibid.; a cross next to Petrus’ name indicates that he died, and the date “22/7 1870” is recorded under his name.

[16] Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne [Polish Genealogical Society] Geneteka, database (https://geneteka.genealodzy.pl/ : accessed 15 March 2025), search result for Klaus births in Podkarpackie, 1872, no. 23, Tomasz Klaus, son of Jakub Klaus and Franciszka Nygus [sic], parish Książnice-Wola Mielecka, born in Wola Mielecka on 3 September 1872, source: parish archives, indexed by Krzysztof Gruszka, accessed 15 March 2025.

[17] Roman Catholic Church of Corpus Christi (Buffalo, Erie, New York, USA), “Deaths, 1902-1916,” p. 68, 1911, no. 139, Thomas Klaus, 28 December 1911; Polish Genealogical Society of New York State.

[18] Ibid., 1875, #23, Helena Klaus, son of Jakub Klaus and Franciszka Nygus [sic], parish Książnice-Wola Mielecka, born in Wola Mielecka on 25 September 1875, source: parish archives, indexed by Krzysztof Gruszka.

[19] Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne [Polish Genealogical Society], Geneteka, database, (https://geneteka.genealodzy.pl/ : accessed 13 March 2025), search result for Klaus deaths in Podkarpackie, 1878, no. 28, Helena Klaus, daughter of Jakub Klaus and Franciszka Liguz, parish Książnice-Wola Mielecka, died in Wola Mielecka on 15 August 1878 at the age of 3 years, source, parish archives, indexed by Krzysztof Gruszka.

[20] Roman Catholic Church of St. Mary Magdalene (Szczucin, Dąbrowa, Małopolska, Poland), Maniów, Liber Baptizatorum, 1836, unnumbered entries in chronological order, Francisca Liguz, 6 February 1836; FamilySearch Library film no. 1958427, items 12-14.

[21] Ibid., Maniów, Akta małżeństw, 1832, Liguz-Warzechow, 28 May 1832; FSL film no.1958428, items 7-8.

[22] See note 20.

[23] Roman Catholic Church of St. Mary Magdalene, (Szczucin, Dąbrowa, Małopolskie, Poland), Liber Baptizatorum, Maniów, 1838, no. 2, Josepha Sophia Liguz, born 11 January 1838; FamilySearch film no. 1958427, Items 12-14.

[24] Ibid., 1840, no. 2, Joannes Liguz, born 01 January 1840; FamilySearch film 1958427, Items 12-14.

[25] “Poland, Church Books, 1568-1990,” database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6VQ2-VSPW?lang=en : accessed 13 March 2025), Joannes Liguz, died 4 January 1840.

[26] Ibid.,1840, no. 3, Sebastianus Liguz, 01 January 1840; FamilySearch film 1958427, Items 12-14.

[27] Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne [Polish Genealogical Society], Geneteka, database, (http://geneteka.genealodzy.pl/ : accessed 13 March 2025), search result for deaths in Malopolska, 1840, no1, Sebastian Liguz, son of Wawrzyniec and Malgorzata, Parish: Szczucin, Place: Maniów, Remarks: 1 day [old], date of death: 2 January 1840, Source: parish archive, Indexed by Marc68.

[28] Roman Catholic Church, St. Mary Magdalene parish (Szczucin, Dąbrowa, Małopolskie, Poland), Liber Baptizatorum, Maniów, 1841, no. 12, Joannes Liguz, 13 June 1841; FamilySearch film no. 1958427, Items 12-14.

[29] “Poland, Church Books, 1568-1990,” database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6VQ2-4HM9?lang=en : accessed 13 March 2025), Joannes Liguz, died 8 September 1841 in Borki, son of Laurentii Liguz and Margaretha Warzczonka.

[30] Roman Catholic Church, St. Mary Magdalene parish (Szczucin, Dąbrowa, Małopolskie, Poland), Liber Baptizatorum, Maniów, 1844, unnumbered entries in chronological order, Josephus Liguz, 2 March 1844, FamilySearch film no.1958427, Items 12-14.

[31] “Poland, Church Books, 1568-1990,” database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6VQ2-QZJW?lang=en : accessed 13 March 2025), Josephus Liguz, died 16 May 1846, son of Laurentii Liguz and Margaretha Marzcrzona [sic].

[32] William F. Hoffman and Jonathan D. Shea, In Their Words: A Genealogist’s Translation Guide to Polish, German, Lain, and Russian Documents: Volume III: Latin (Language & Lineage Press, 2018), p. 272.

[33] Roman Catholic Church, St. Mary Magdalene parish (Szczucin, Dąbrowa, Małopolskie, Poland), Liber Matrimoniorum [Book of marriages], Maniów, 1848, Joannes Podkówka and Margaretha Ligus, nee Warzecha, 1 November 1848; FamilySearch film no. 1958428, Items 7-8.

[34] Ibid., Liber Baptizatorum, Maniów, 1849, no. 18, Thomas Podkówka, 5 November 1849; FamilySearch film no. 1958427, Items 12-14.

[35] Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne [Polish Genealogical Society], Geneteka, database, Geneteka.genealodzy.pl, (http://geneteka.genealodzy.pl/ : accessed 14 March 2025), search result for Podkówka deaths in Malopolskie, 1873, no. 57, Tomasz Podkówka, son of Jan and Malgorzata Warzecha, Parish: Szczucin, Place: Maniów, Remarks: 25 years [of age], died 16 November 1873, source: parish archive, indexed by Marc68.

[36] Roman Catholic Church, St. Mary Magdalene parish (Szczucin, Dąbrowa, Małopolskie, Poland), Liber Baptizatorum [birth records], Maniów ,1852, no. 5, Agatha Podkówka, 1 February 1852; FamilySearch film no. 1958427 Items 12-14.

[37] Roman Catholic Church, St. Mary Magdalene Parish (Szczucin, Malopolskie, Poland), “Akta stanu cywilnego Parafii Rzymskokatolickiej w Szczucinie,” Ksiega Aktów Zgonów od 1890 – 1913 [Book of Death Certificates from 1890 – 1913], p. 140, Maniów, 1910, no. 6, Agata Liguz, died 6 March 1910; digital image, Szukajwarchiwach (https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl : accessed 16 March 2025), reference code 33/630/0/-/3, image 74 of 123.

[38] Roman Catholic Church, St. Mary Magdalene parish (Szczucin, Dąbrowa, Małopolskie, Poland), Akta małżeństw [Marriage records] 1786-1866, 1856, Maniów, unnumbered entries in chronological order, Antonius Słowik and Margaretha Podkowka, 27 January 1856; FamilySearch film no. 1958428, Item 3.

[39] There is no clear match in Geneteka for a death record for Jan Podkówka. An online conception date calculator indicates that Agata Podkówka would have been conceived between 20 April 1851 and 27 April 1851. That suggests that Jan Podkówka died between 20 April 1851 and 26 January 1856.

The only death for a Jan Podkówka in Małopolskie that comes close is that of Jan Podkówka, who died in Maniów on 1 December 1851. He was age 52, which suggests a birth circa 1799, consistent with his age at the time of his marriage to Małgorzata (Warzecha) Liguz, but he was reported to be the husband of Katarzyna, not Małgorzata. If this death record is the correct one for Jan Podkówka, husband of Małgorzata, then it’s curious that Agata Podkówka’s baptismal record from February 1852 did not mention that her father was deceased. However, it’s noteworthy that Jan and Małgorzata’s marriage record, and the birth record for their son Tomasz, indicate that he was living in house number 34 in Maniów. Agata’s birth record (presumably made after Jan’s death) indicates that she was born in house number 19 in Maniów, consistent with the prediction that Małgorzata would have had to move in with other family members after Jan’s death.

[40] Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne [Polish Genealogical Society], Geneteka, database, (http://geneteka.genealodzy.pl/ : accessed 17 March 2025), search result for Antoni Slowik in Małopolskie, Deaths, 1864, no. 4, Antoni Slowik, parish: Szczucin, place: Borki, remarks: house no. 33, 58 years, husband of Malgorzata Warzecha, died 4 April 1864; source: parish archive, indexed by Marc68.

[41] Ibid., search result for surnames Slowik and Warzecha in Małopolskie, Births, 1857, no. 5, Katarzyna Slowik, daughter of Antoni and Malgorzata Warzecha, parish: Szczucin, place: Borki, remarks: house number 33, date of birth, 14 February 1857, source: parish archive, indexed by Marc68.

[42] Roman Catholic Church, St. Mary Magdalene Parish (Szczucin, Małopolskie, Poland), “Akta stanu cywilnego Parafii Rzymskokatolickiej w Szczucinie,” Ksiega Aktów Zgonów od 1890 – 1913 [Book of Deaths from 1890 – 1913], p. 184, Delastowice, 1902, no. 2, Catharina Lasak, died 25 April 1902; digital image, Szukaj w Archiwach (https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl : accessed 17 March 2025), reference code 33/630/0/-/3, scan 96 of 123.

[43] Polskie Towarzystwo Genealogiczne [Polish Genealogical Society], Geneteka, database, (http://geneteka.genealodzy.pl/ : accessed 17 March 2025), search result for surnames Slowik and Warzecha in Małopolskie, Births, 1859, no. 11, Ignacy Slowik, son of Antoni and Malgorzata Warzecha, parish: Szczucin, place: Borki, house no. 33, remarks: house no. 33, date of birth, 28 July 1859, source: parish archive, indexed by Marc68.

[44] Ibid., search result for Ignacy Slowik in Małopolskie, Deaths, 1937, no. 7, Ignacy Slowik, parish: Szczucin, place: Maniów, remarks: age 78, husband of Helena Łaska, date of death, 5 October 1937, source: parish archive, indexed by Marc68.

[45] Ibid., search result for Zofia Liguz in Malopolskie, Marriages, 1862, Wojciech Krupa, son of Walenty and Marianna Krzyzek, and Zofia Liguz, daughter of Wawrzyniec and Malgorzata Warzecha, parish: Szczucin, remarks: groom’s age, 33, bride’s age, 24; place: Borki, date of marriage, 27 July 1862.

[46] Roman Catholic Church, St. Mary Magdalene parish (Szczucin, Dąbrowa, Małopolskie, Poland), Księga Aktów Zgonów [Book of death certificates], 1890-1913, 1892, no. 1, Margaritha Liguz Podkówka Słowik nee Warzecha; imaged as “Akta stanu cywilnego Parafii Rzymskokatolickiej w Szczucinie, 1890-1932,” Szukaj w Archiwach (https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/en/jednostka/-/jednostka/19224209 : 5 April 2024), Sygnatura 33/630/0/-/3, scan 5 of 123.