The longer I research, the more I am convinced of the unstoppable power of cluster research, combined with autosomal DNA testing, when it comes to breaking through genealogical brick walls. Cluster research is also known as FAN research—genealogical research into an ancestor’s friends, associates and neighbors—and this method has proven to be very successful when the paper trail dries up, and historical records cannot be found which offer direct evidence for parentage or place of origin.

Last autumn, this combination helped me break through a long-standing brick wall, and discover the place of origin of my Causin/Cossin ancestors from Pfetterhouse, Alsace, France. Bolstered by that success, I’ve been attempting to utilize that same magic combination of FAN plus DNA research to discover the origins of my Murre/Muri ancestors, who immigrated to Buffalo, New York in 1869 from somewhere in Bavaria.

From Bavaria to Buffalo: The Joseph Murre Family

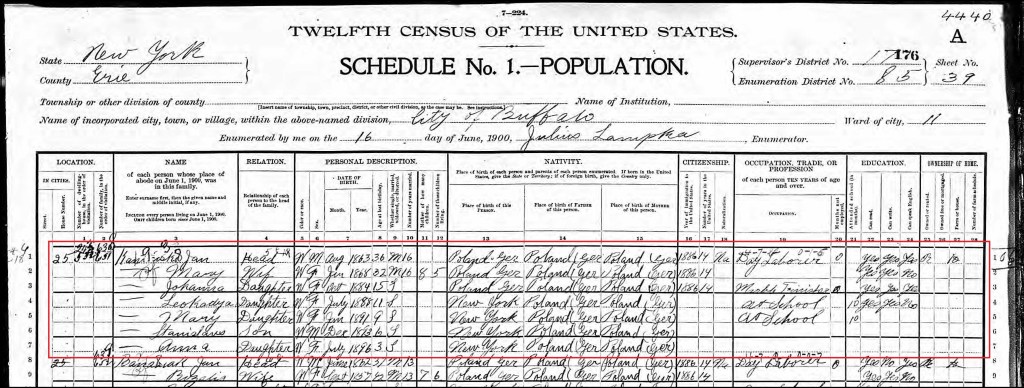

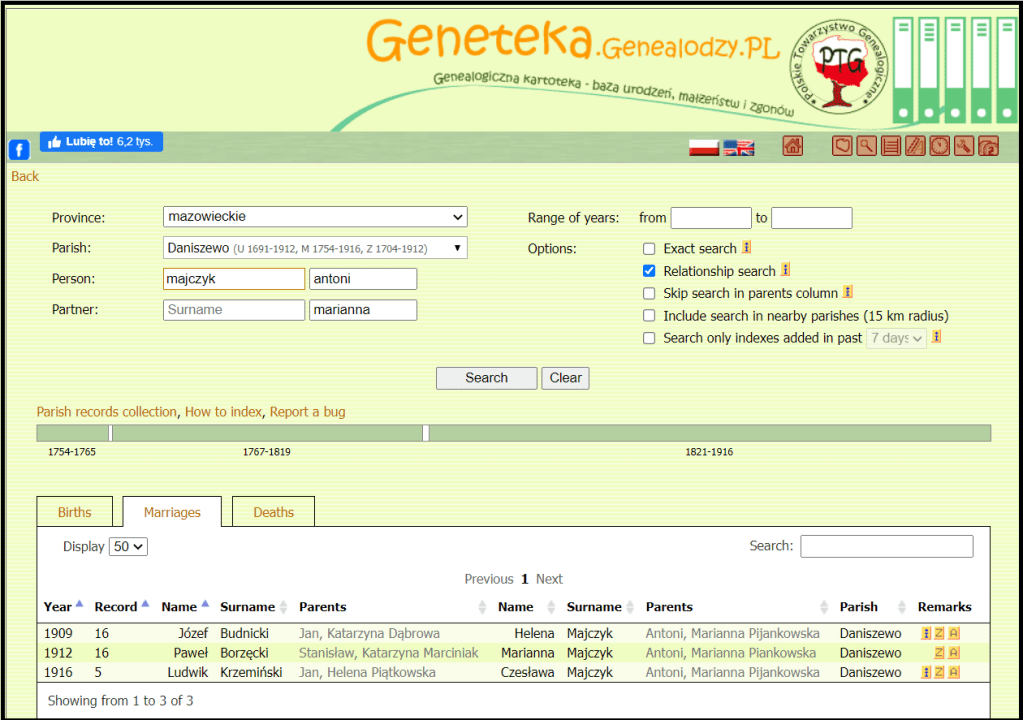

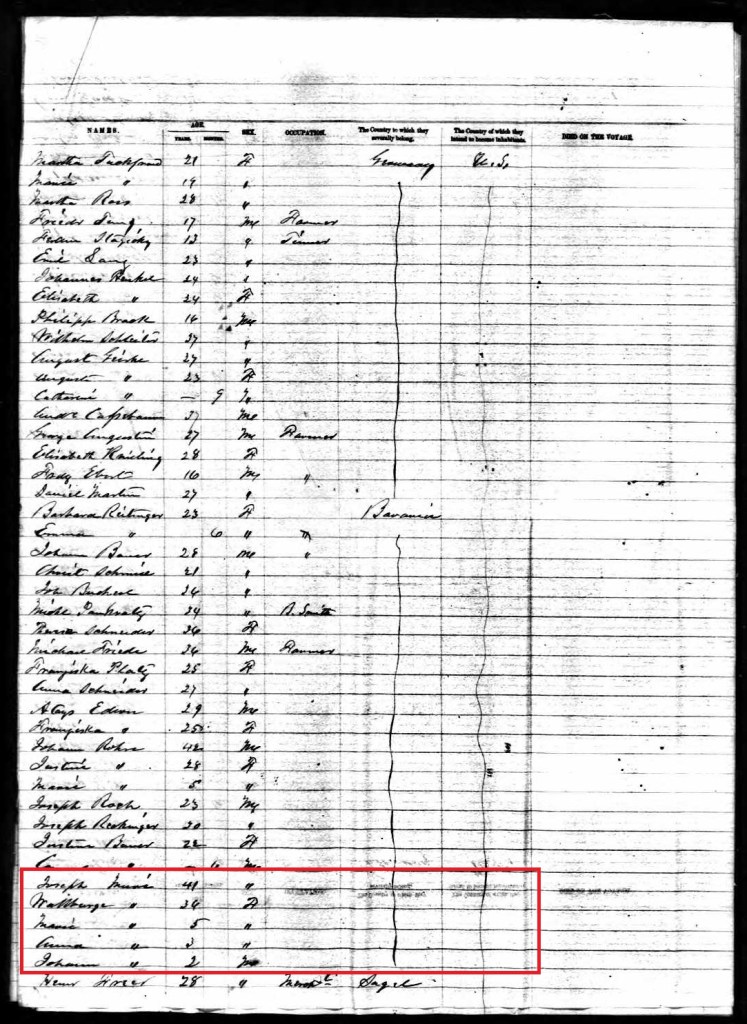

Let me start with a brief introduction to my 3x-great-grandparents, Joseph and Walburga (Maurer) Murre. Joseph Murre (or Murrÿ, Muri, Murri, Murrie, etc.) was born circa 1825 in Bavaria, Germany.1 Around 1862, he married Walburga Maurer, who was born circa 1835.2 They had at least three children while in Germany: Maria/Mary Murre, born circa 1863; Anna Murre (my great-great-grandmother), born 27 September 1865; and Johann/John F. Murre, born circa April 1867.3 The Murre family emigrated from the port of Bremen, arriving in New York on 3 April 1869 aboard the SS Hansa.4 Their passenger manifest is shown in Figure 1.

Unfortunately, the manifest does not specify a place of origin beyond simply “Bavaria,” and neither have any other records discovered to date been informative in that regard—including naturalization records and church records, which are so often helpful in identifying an immigrant’s place of origin.

Three more children were born to Joseph and Walburga Murre in Buffalo: Josephine, born in 1869, Alois/Aloysius Joseph, born in 1872, and Frances Walburga, born in 1876.5 Walburga Murre—who became known as Barbara in the U.S.—died on 18 September 1886 and is buried in the United German & French Cemetery in Cheektowaga, New York.6 Her husband, Joseph, was living in the Erie County Almshouse at the time of the 1900 census, and he died in 1905.7 He, too, is buried in the United German & French Cemetery in Cheektowaga, albeit in a different plot from the one where Walburga is buried.

While it would oversimplify the situation considerably to state that this summary is “all” that was known about the Murre/Maurer family, the fact remains that thus far, I have not identified any siblings or parents for either Joseph Murre or Walburga Maurer, nor have I been able to identify their place of origin in Bavaria.

Step 1: Use DNA to Light the Way

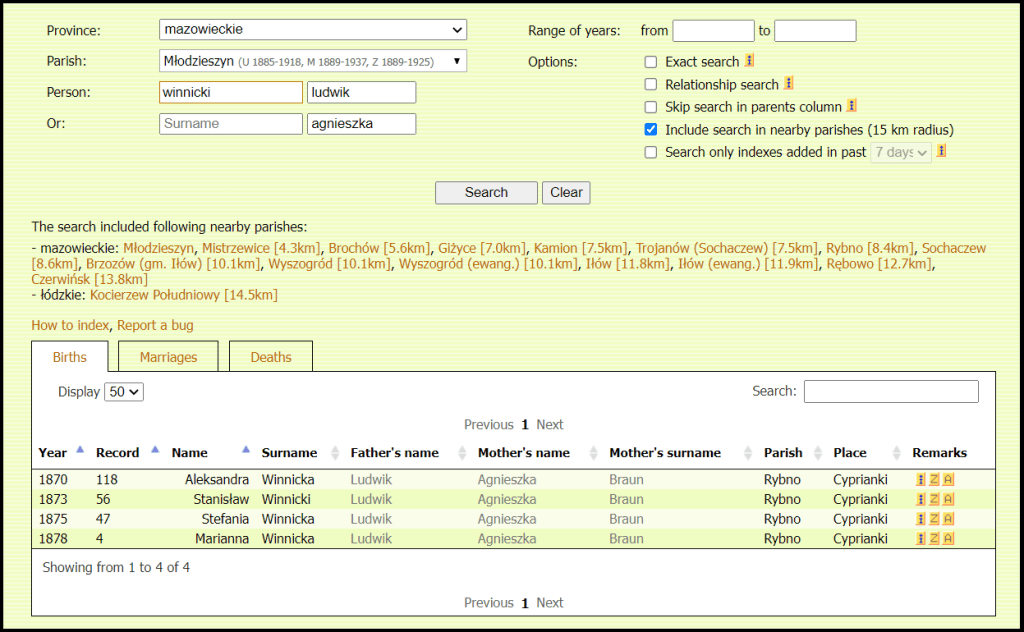

When faced with a similar research question for my Causin/Cossin line, I believe I missed an opportunity by failing to exploit genetic genealogy methodology early on in the research. Now that I’m older and wiser, I decided to tackle my Murre/Maurer origins question using genetic genealogy methods right from the start. Specifically, I began by examining the Collins-Leeds Method autoclusters of my Dad’s autosomal DNA matches, gathered from all his Ancestry DNA matches who share between 20 cM (centimorgans, a unit of genetic distance) and 400 cM of DNA with him. These autoclusters are created by the DNAGedcom Client, an app available with a subscription to DNAGedcom. The clusters are displayed in a matrix that resembles the one shown in Figure 2.

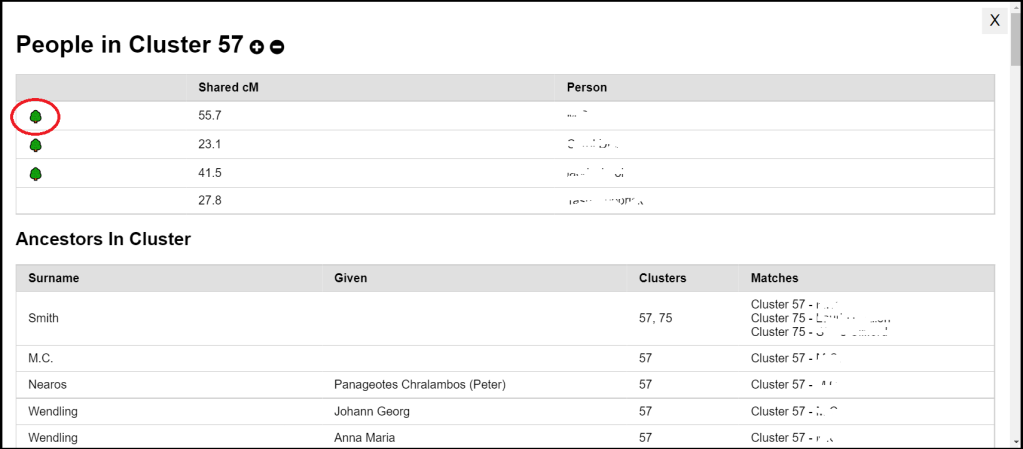

At the time I ran this autocluster analysis, Dad had 385 Ancestry DNA matches who met the specified requirements of sharing between 20 and 400 cM DNA with him. So, Figure 2 shows only a portion of the matrix, which is set up as a grid with those 385 names along the top and also along the left side. Those 385 people are organized into clusters based on common ancestry, and Cluster 57, indicated by the red arrow, is the cluster to focus on to start. Clicking the popup box, “View Cluster,” brings up the image shown in Figure 3.

The green tree icon (circled in red) indicates a DNA match with a family tree linked to his or her test results; names of matches (in the “Person” column) have been redacted for privacy. By scrolling down through the list of Ancestors in Cluster, or by examining the trees (when available), I was able to determine that two of these DNA matches are descendants of Josephine (Murre) Hummel—the sister of my great-great-grandmother, Anna (Murre) Boehringer. The third match lacks a family tree, so it’s not immediately clear how we are related; however, these initial findings imply that we must be related through DNA passed down from ancestors of either Joseph Murre or Walburga Maurer.

The fourth member of that Cluster 57, whom I’ll call L.O., is even more interesting, because her family tree indicates that she is the great-granddaughter of German immigrants Frank and Matilda Maurer of Buffalo, New York. L.O. is the DNA match who shares 41.5 cM DNA with my dad, in the list of people in Cluster 57 shown in Figure 3. At this point, I did not have any information on Frank Maurer’s ancestry. But the fact that he shared a surname with Walburga Maurer, combined with the fact that one of his descendants shares DNA with three documented descendants of hers, strongly suggested that (a) Cluster 57 is a Maurer DNA cluster and not a Murre DNA cluster, and (b) Frank must somehow be related to Walburga.

Hoping to gather more data, I examined the Collins-Leeds Method autoclusters that were generated from gathering Dad’s DNA matches who shared between 9 cM and 400 cM DNA with him. By dropping the minimum threshold for inclusion in the analysis all the way down to 9 cM, I picked up DNA matches who are related more distantly, and the total number of individuals included in the analysis jumped from 385 to 1,651. The cluster that contains the same individuals found in Cluster 57 of the previous analysis, is now numbered as Cluster 334, shown in Figure 4.

Examination of the new and improved version of that “Maurer Cluster” (Cluster 334) revealed that there’s some overlap with the adjacent Cluster 335, as well as some other DNA matches (336–342) that are more loosely related, creating a supercluster. That supercluster includes all the greyed-out boxes around Clusters 334 and 335.

Inspection of available family trees for people in the 334–342 supercluster produced the following data (Figure 5):

| Match ID | Shared cM with Dad | Pedigree notes |

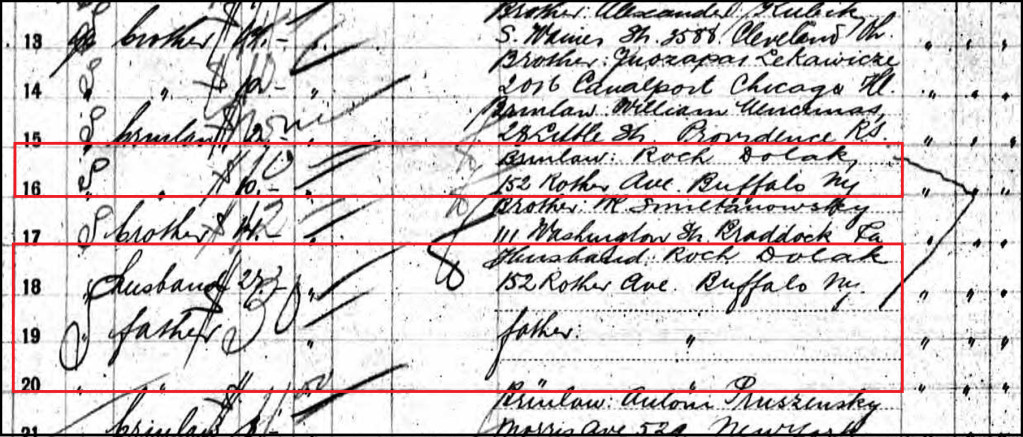

| L.O. | 41.5 cM | Granddaughter of Eleanor Maurer, daughter of Franz Maurer & Matilda Grenz |

| M.L. | 11.1 cM | Great-granddaughter of John J. Maurer, son of Franz Maurer & Matilda Grenz |

| C.M. | 11.0 cM | Grandson of Joseph J. Maurer, son of Franz Maurer & Matilda Grenz |

| R.H. | 10.8 cM | Grandson of John J. Maurer, son of Franz Maurer & Matilda Grenz |

| D.U. | 9.2 cM | Grandson of Eleanor Maurer, daughter of Franz Maurer & Matilda Grenz |

| T.M. | 10 cM | Grandson of John J. Maurer, son of Franz Maurer & Matilda Grenz |

The DNA matches summarized in Figure 5 were in addition to other DNA matches from that cluster who were already known to me as descendants of Joseph and Walburga (Maurer) Murre.

Most of these matches are in the 10 cM range, with the outlier being L.O., who shares roughly 42 cM with my dad, and this variability may be due simply to the randomness of DNA inheritance through recombination. However, other possibilities exist, such as the possibility that L.O. shares more than the expected amount of DNA with Dad because she’s also related to him in some other way, besides just the Maurer connection. That’s a question for another day, but in any case, there’s ample DNA evidence here to suggest that the genetic link between my family and all these DNA cousins lies in that Maurer DNA. Nonetheless, the precise relationship between Franz Maurer and my 3x-great-grandmother, Walburga (Maurer) Murre, remains unclear. Were they siblings, or perhaps first cousins? If we hypothesize that Franz and Walburga were siblings, then that would mean that Dad and all these great-grandchildren of Franz Maurer would be third cousins once removed (3C1R). While it’s within the realm of statistical possibility for 3C1R to share only 10 cM DNA, according to data from the Shared cM Project, a more distant relationship between Franz and Walburga is more probable.

Step 2: Research Franz Maurer’s Family in Historical Records

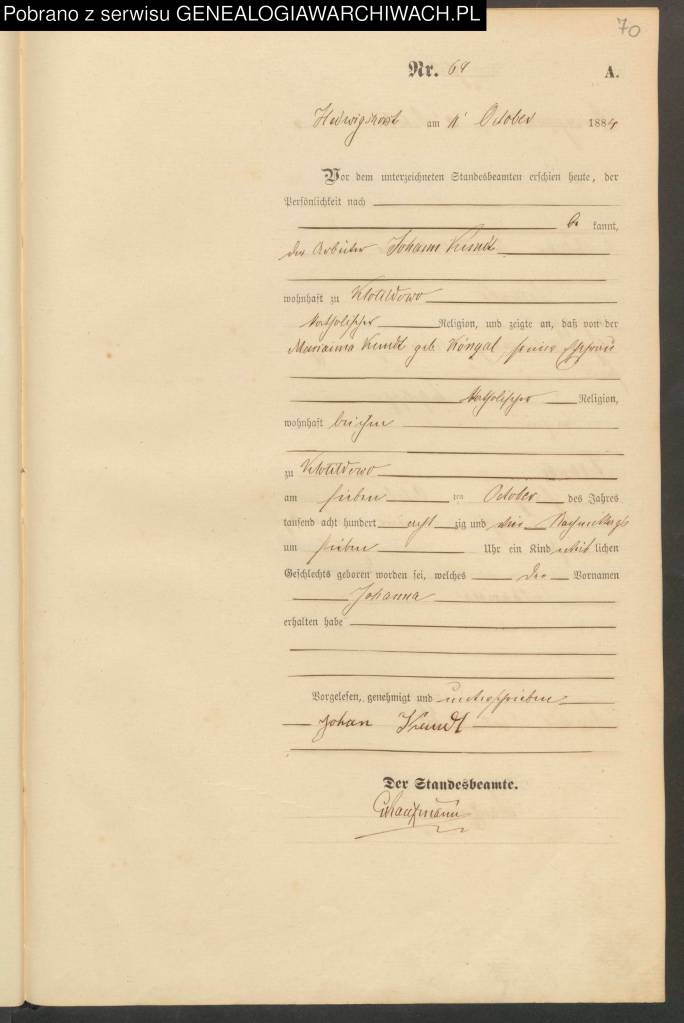

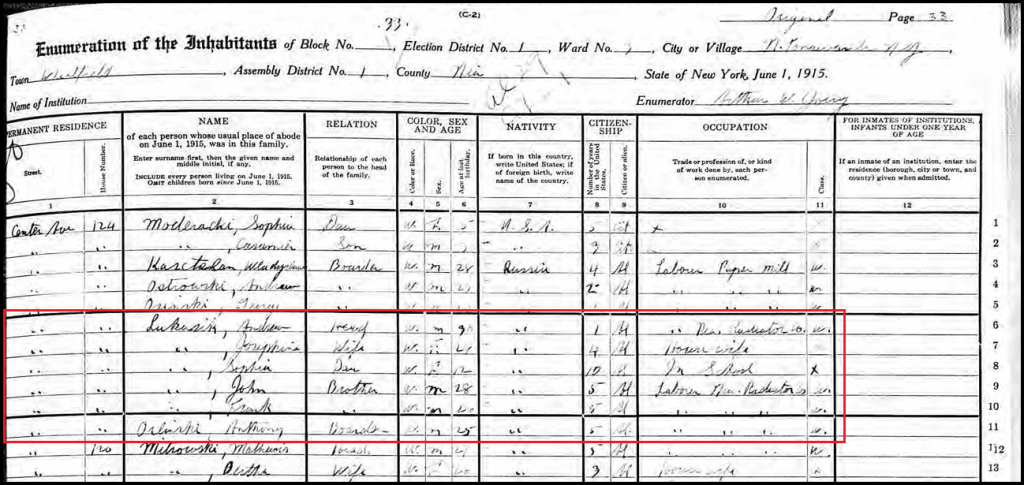

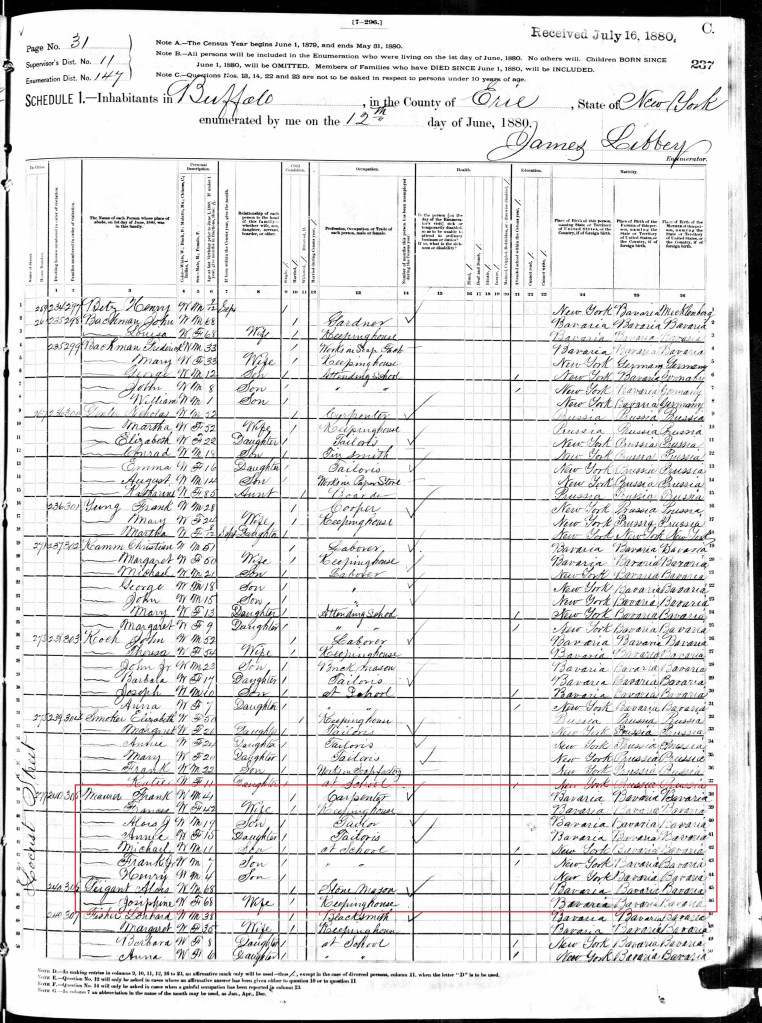

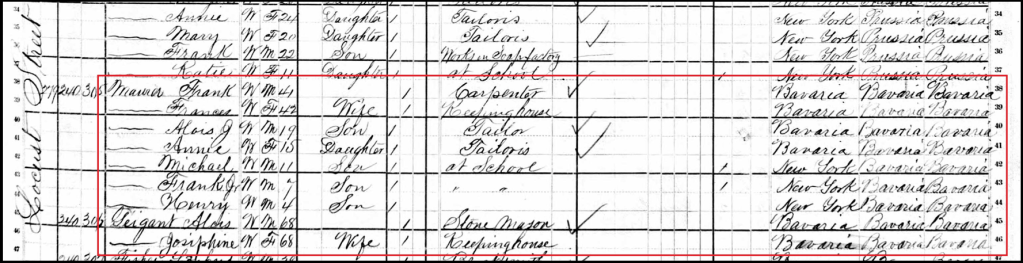

Now that we’ve identified a family of interest, who was Franz Maurer, and what evidence can be found in historical records that might offer some clues for our research question? Preliminary research indicated that Franz/Frank Maurer was born circa 1839 in Bavaria, and was married to Franziska/Frances Geigand in Germany. Figure 6 shows the family in the 1880 census.8

Franz was a carpenter, born in Bavaria, and the couple had two children while in Germany: a son, Alois, born circa 1861, and a daughter, Anna, born about 1865. They immigrated in 1867,9 and settled in Buffalo, New York, in the same parish where my Murre family would settle two years later—St. Boniface, formerly located at 145 Mulberry Street. Church records show that another son, Joseph, was born to Franz and Franziska on 18 August 1867, followed by Michael on 21 July 1869.10 Twin boys, Joannes Aloisius and Franciscus (as they were identified in their Latin baptismal records), were born on 2 February 1872,11 but they both died of smallpox that summer, which also took the life of four-year-old Joseph.12 Another son, Frank, was born on 26 June 1873, followed by Henry on 14 July 1876.13 A daughter, Francisca, born 18 August 1880,14 must also have died in infancy, because she disappears from the records. She is not, however, buried in the same cemetery plot as many of the other Maurer children who died in childhood.

On 15 April 1881, Franziska/Frances Maurer died,15 leaving behind her husband and five living children, ranging in age from about 5 years to 20 years old. Four months later, on 22 August 1881,16 Franz remarried a fellow German immigrant, 33-year-old Franziska (Eppler or Ebler) Schabel, a widow whose previous husband, Frank Schabel, died in April 1880.17 At the time of her remarriage, Frances was the mother of two children, Frank Schabel, Jr. (about age 4), and Rose Schabel, who was barely two years old.18 Although Frank Jr. retained his biological father’s surname, Rose was subsequently known as Rose Maurer, and she identified her father as Francis Maurer—not Schabel—on her marriage record.19 Although Frances was still within her childbearing years when she married Frank Maurer, no children from this marriage have been discovered thus far.

The second Frances Maurer must have died before 1888, because Franz Maurer remarried for the third time on 24 January of that year.20 Oddly, there is no evidence for Frances’ death in the Buffalo, New York, death index 1885–1891. However, there may have been a miscommunication with the civil clerks when the certificate was recorded, because there is a death certificate for a Frank Marer (sic) in that time period, which might be that of Frances, despite the masculine version of the given name.21 (Research is ongoing.)

Franz Maurer’s new bride was 34-year-old Matilda Grenz, another German immigrant, and four children were born to this couple: Joseph, on 15 January 1889; Matilda, on 30 April 1891, John, on 21 December 1892, and Eleanor, on 22 January 1897.22 Franz/Frank Maurer, Sr., died in 1910 and is buried in the United German & French Cemetery.23 In 1924, his wife, Matilda, passed away, and she is buried by his side.24

Step 3: Confirm FAN Club Membership

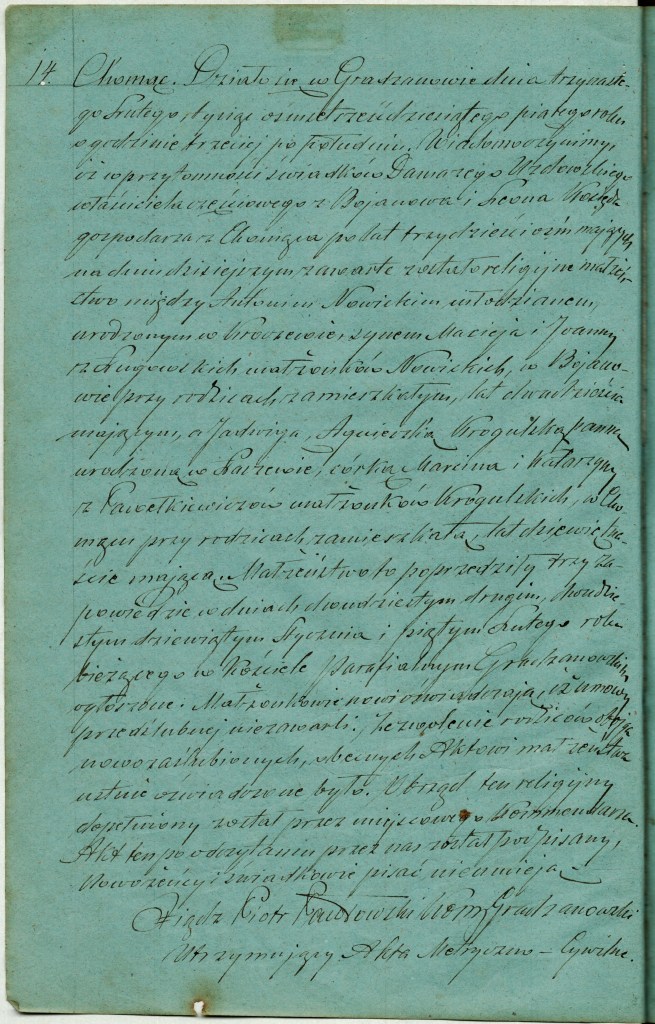

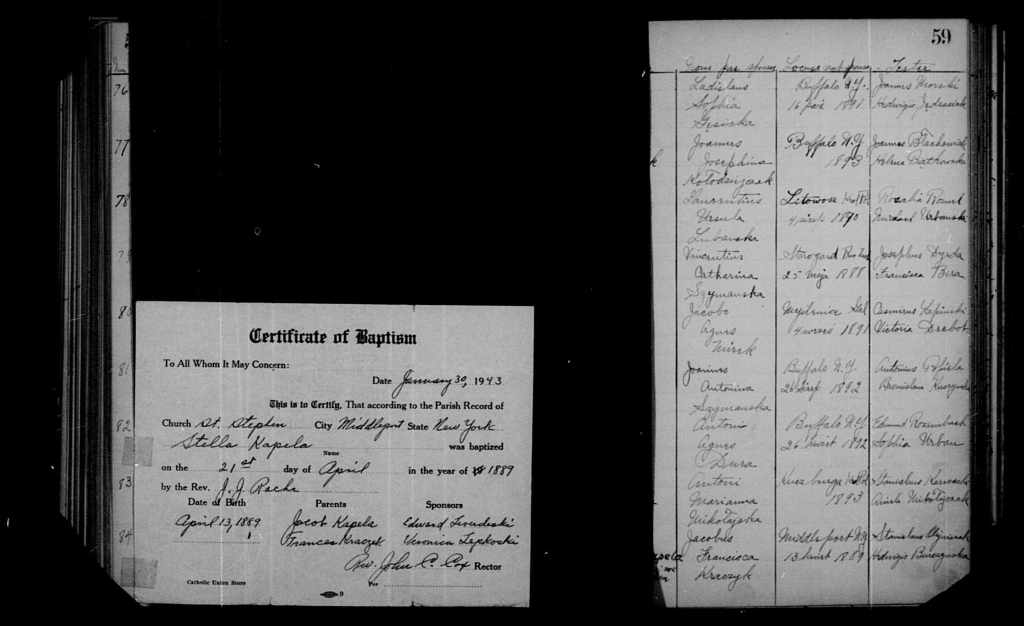

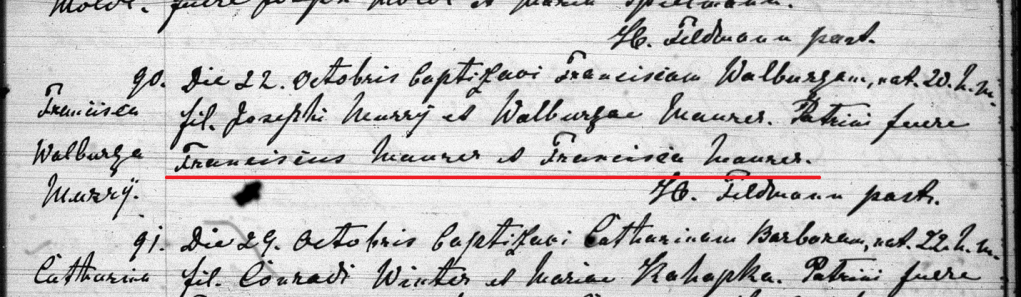

As expected, evidence from Joseph and Walburga Murre’s FAN club confirms the importance of the Franz Maurer family to my quest for the origins of my Maurer/Murre ancestors. Joseph and Walburga Murre named Franz and Franziska Maurer as godparents to their youngest child, Frances Walburga Murre, whose baptismal record from St. Boniface church is shown in Figure 7.25

Interestingly, for both of their other Buffalo-born children, Josephine and Alois Joseph, they named as godparents Alois Geigand and his wife, Josephine. Josephine Murre’s baptismal record is shown in Figure 8.26

Cemetery data from United German and French Cemetery, where Walburga and Joseph were buried, confirm the close relationship between the Maurer and Geigand families. The lot where Walburga was laid to rest was a large one, with at least 20 burials in it, owned by Alois Geigand and Frank Maurer.27 Of the twenty burials, all but four of them have been identified as descendants of Maurer or Geigand families. (Those remaining four burials may also be related, but currently their connection to these families is unclear.) The 1880 census, shown previously in Figure 6, also illustrates the strong links between the families, since they were living in the same house at 240 Locust Street at that time. A detail from this census is shown in Figure 9.

According to this census, Alois and Josephine Geigand were both 68 years old, which implies that they were born circa 1812. These ages suggest that perhaps they might be the parents of Frances (Geigand) Maurer, and I’m hoping that her burial record from St. Boniface might shed some light on that.

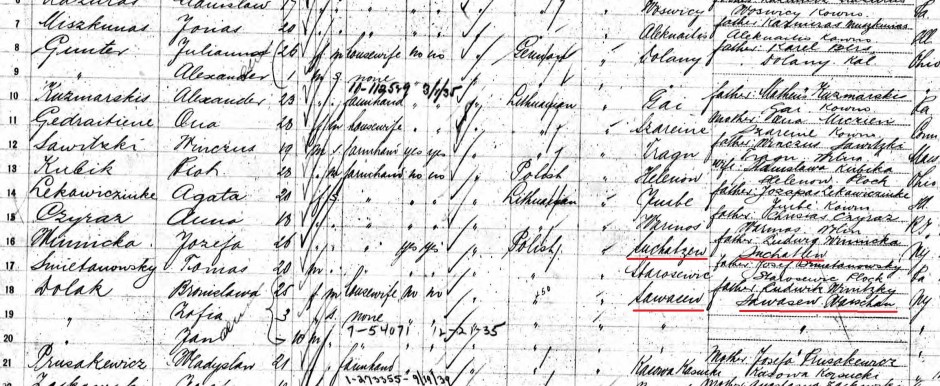

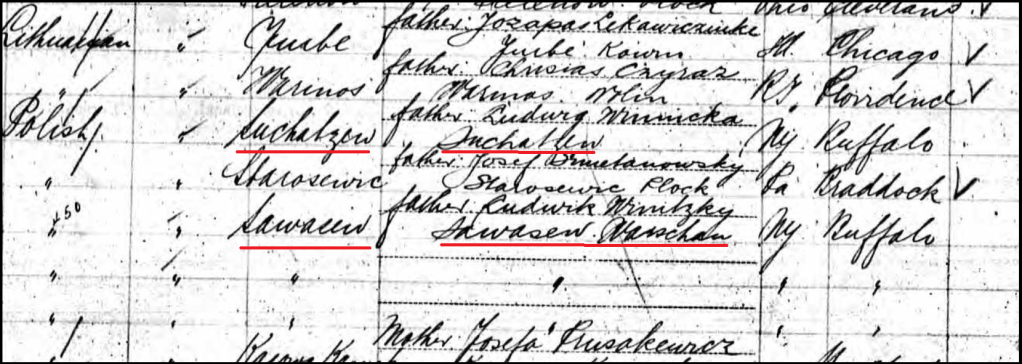

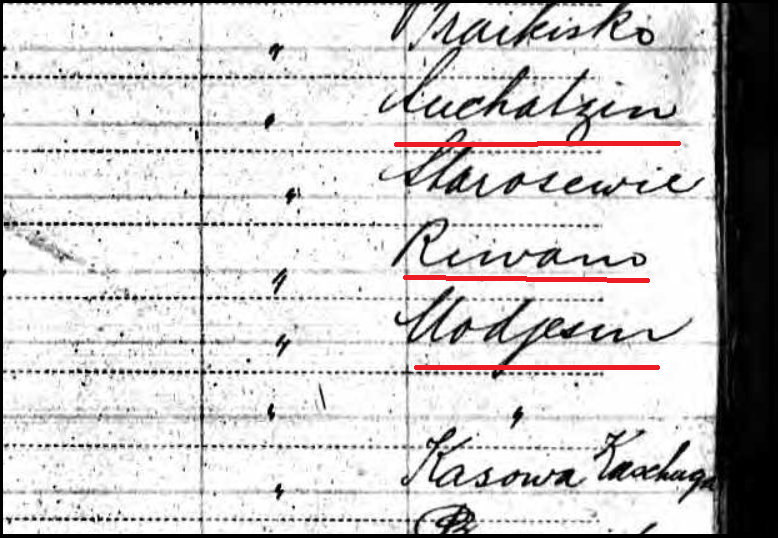

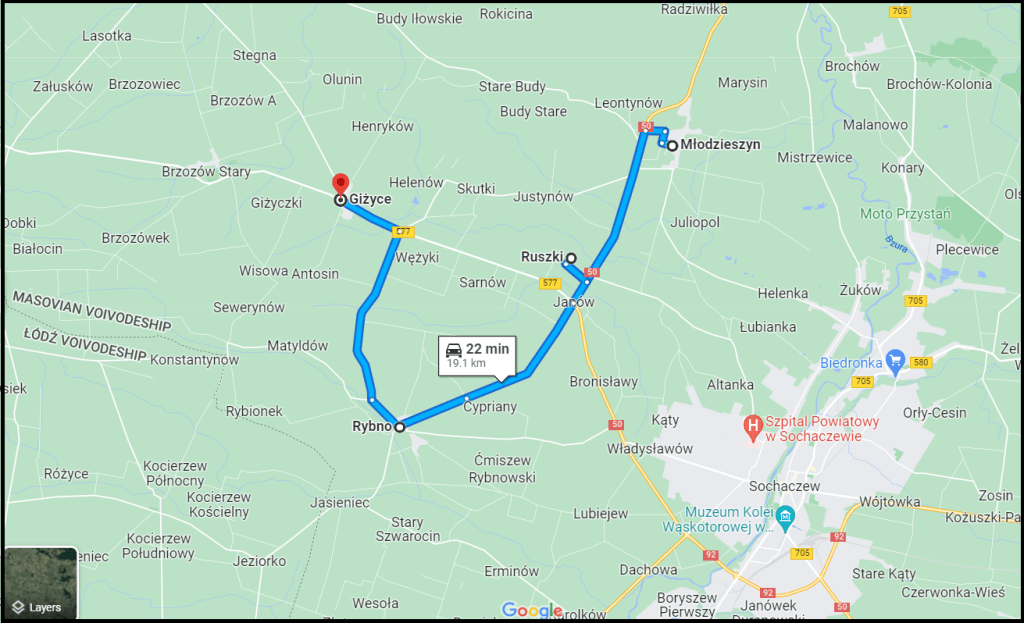

This brings us to the Hamburg emigration manifest for these folks, the document that gives me a glimmer of hope that I might be able to discover the origins of my Maurer/Murre family (Figure 10).28

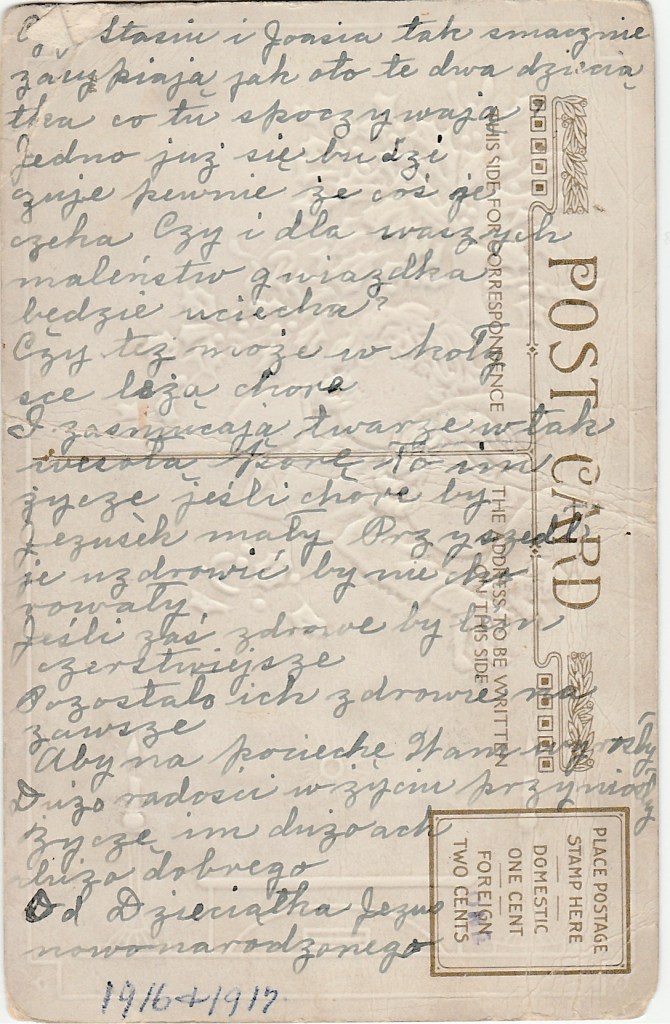

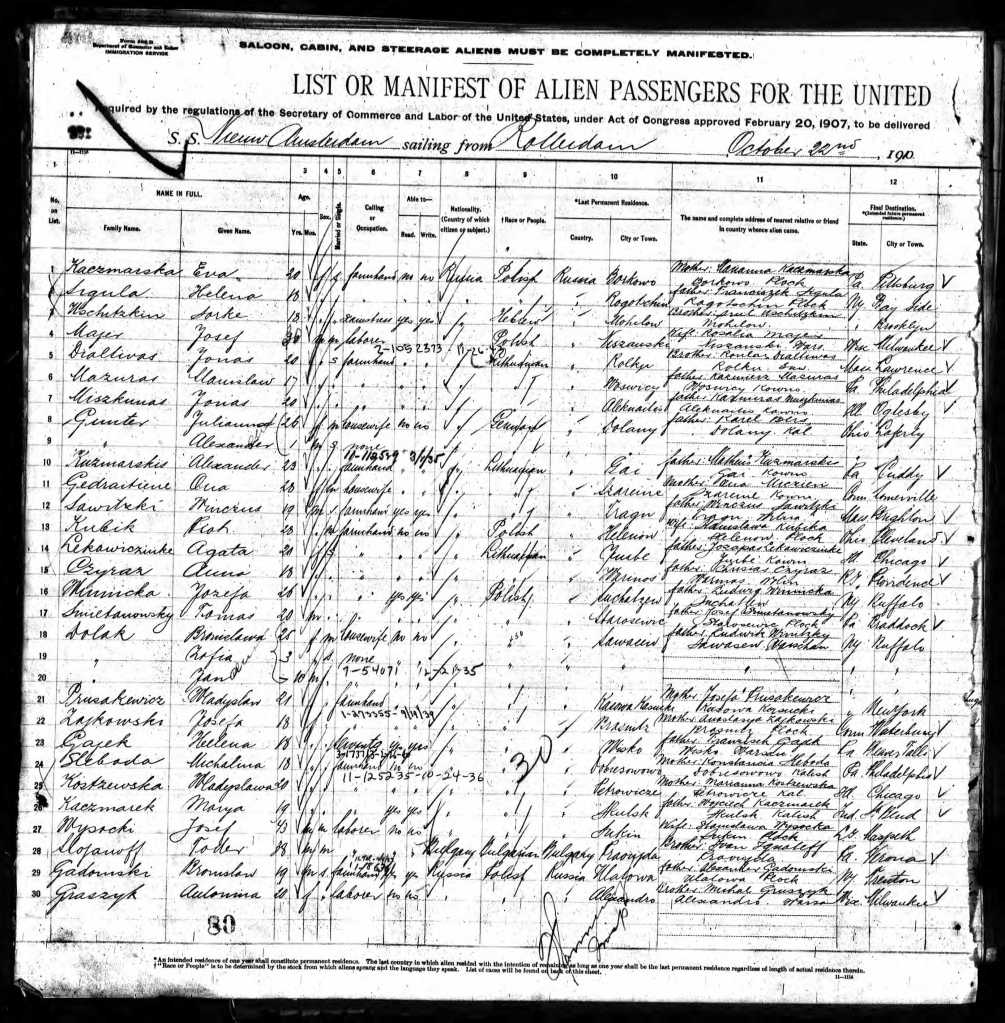

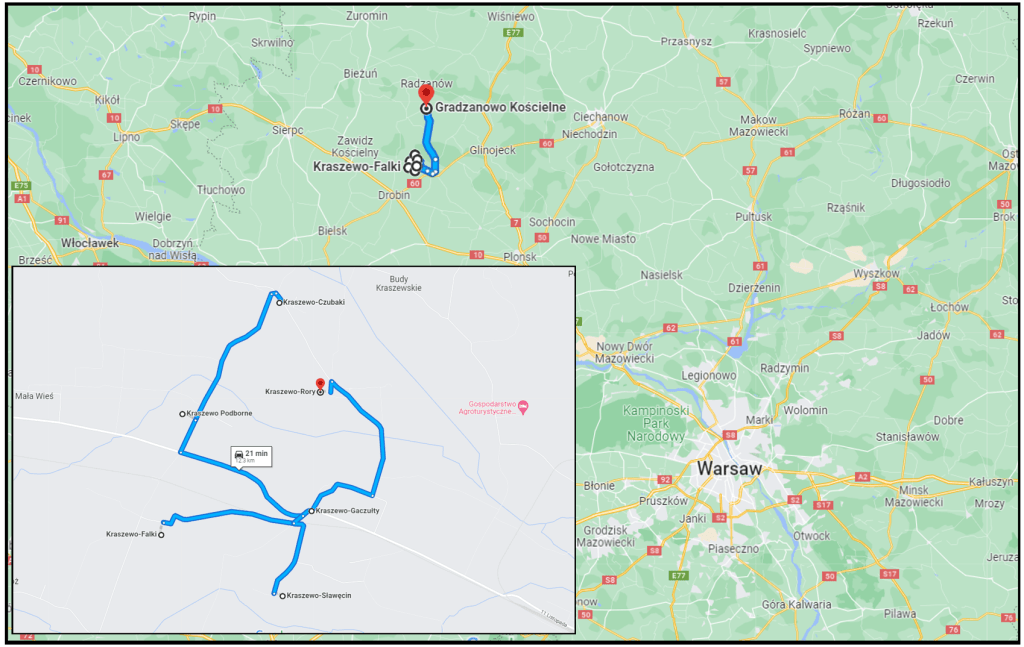

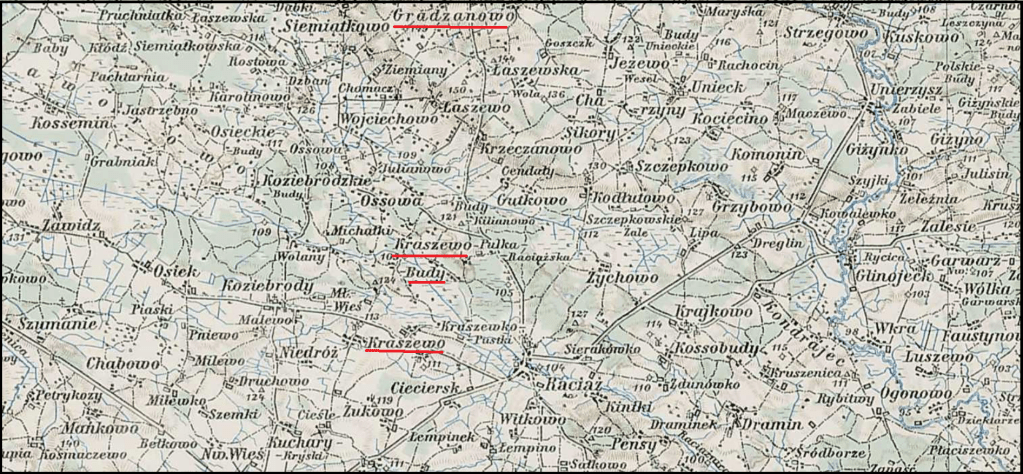

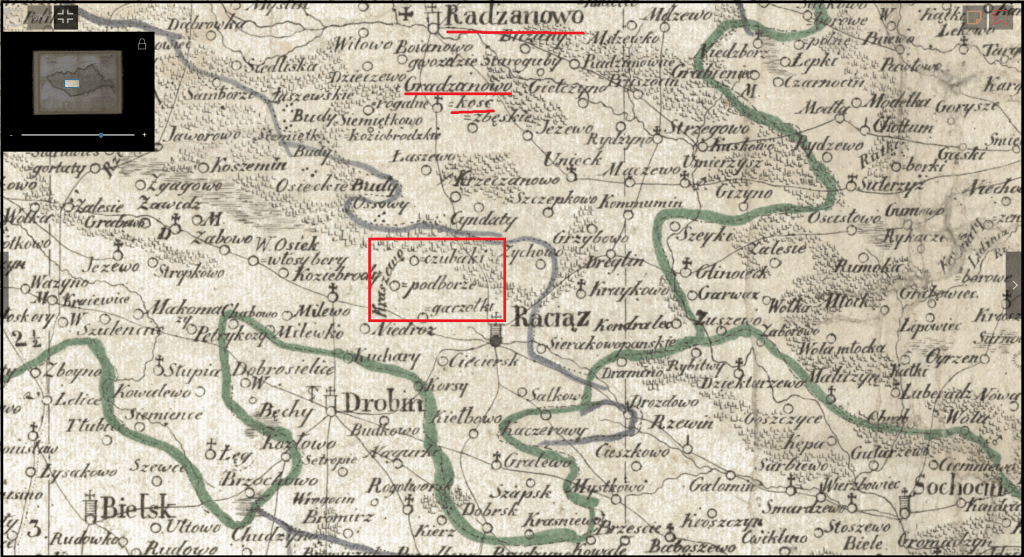

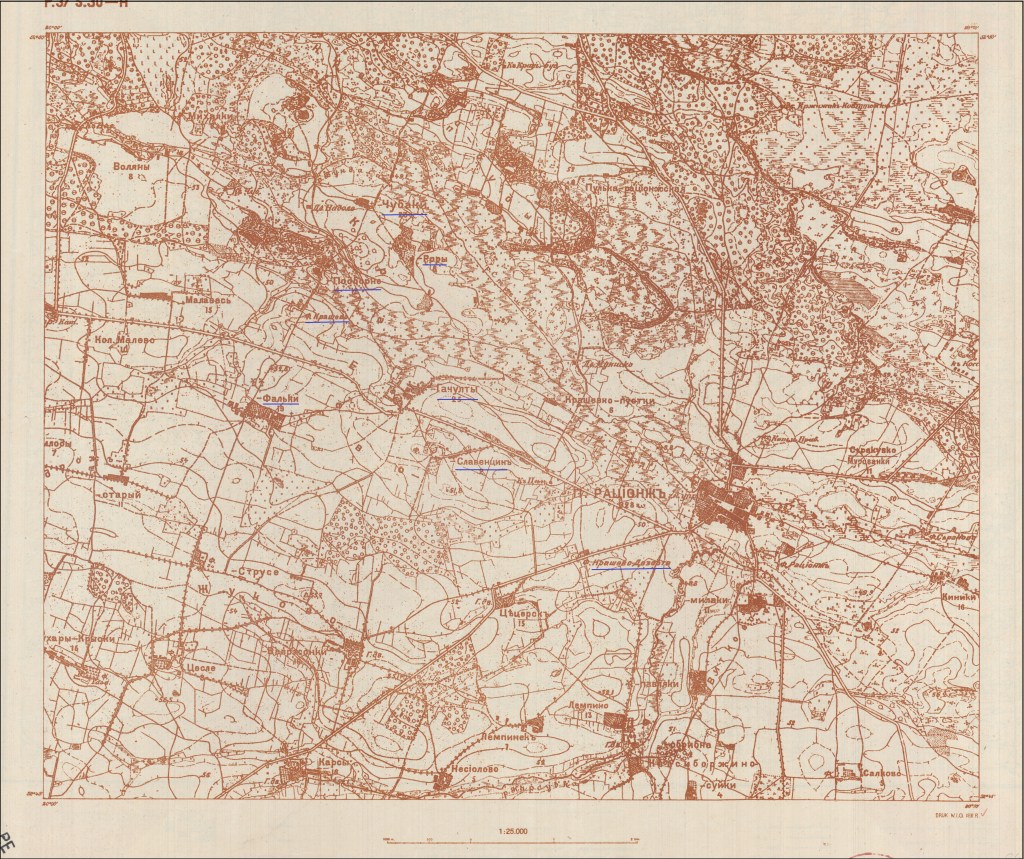

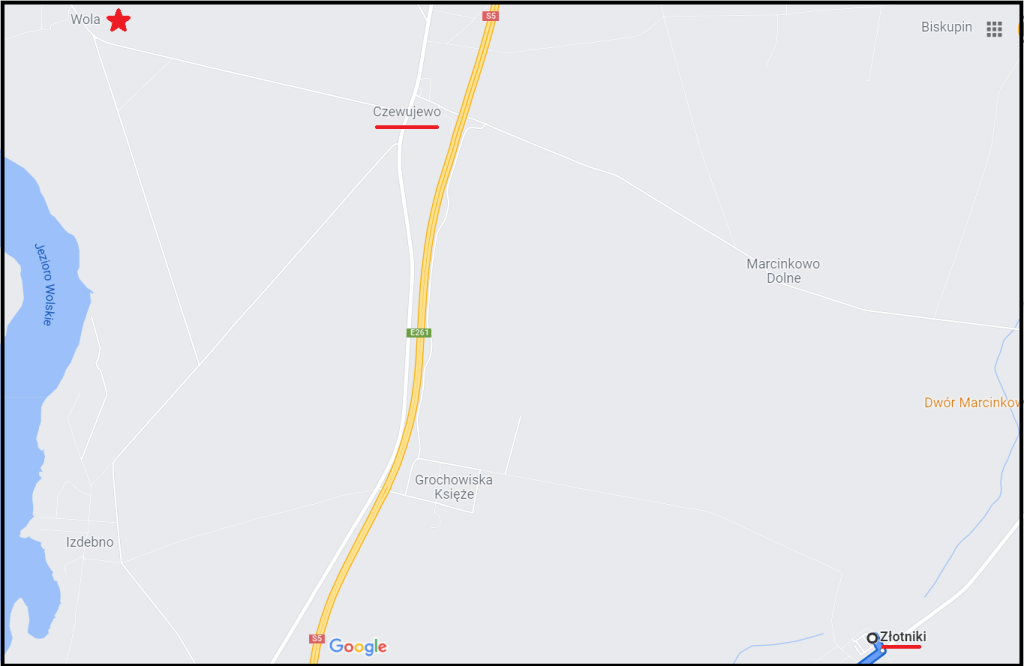

This manifest is irrefutably the correct one for these families. The names and ages of all passengers line up perfectly with data from U.S. records, confirming that 55-year-old laborer, Alois Geigand (indexed as Geigant), and his 54-year-old wife, Josephine, traveled to the U.S. with their two children, 24-year-old Georg and 17-year-old Walbur (sic), aboard the SS Victoria, departing from Hamburg on 1 May 1867. Traveling with them were the family of Franz (indexed as “Fraz”) Maurer, a 23-year-old carpenter; his wife, Franziska, and two children, Alois and Anna. Their place of origin was indexed by Ancestry as Waldmünchen, Bayern—a town in Bavaria, Germany, that’s barely two miles from the Czech border (Figure 11).

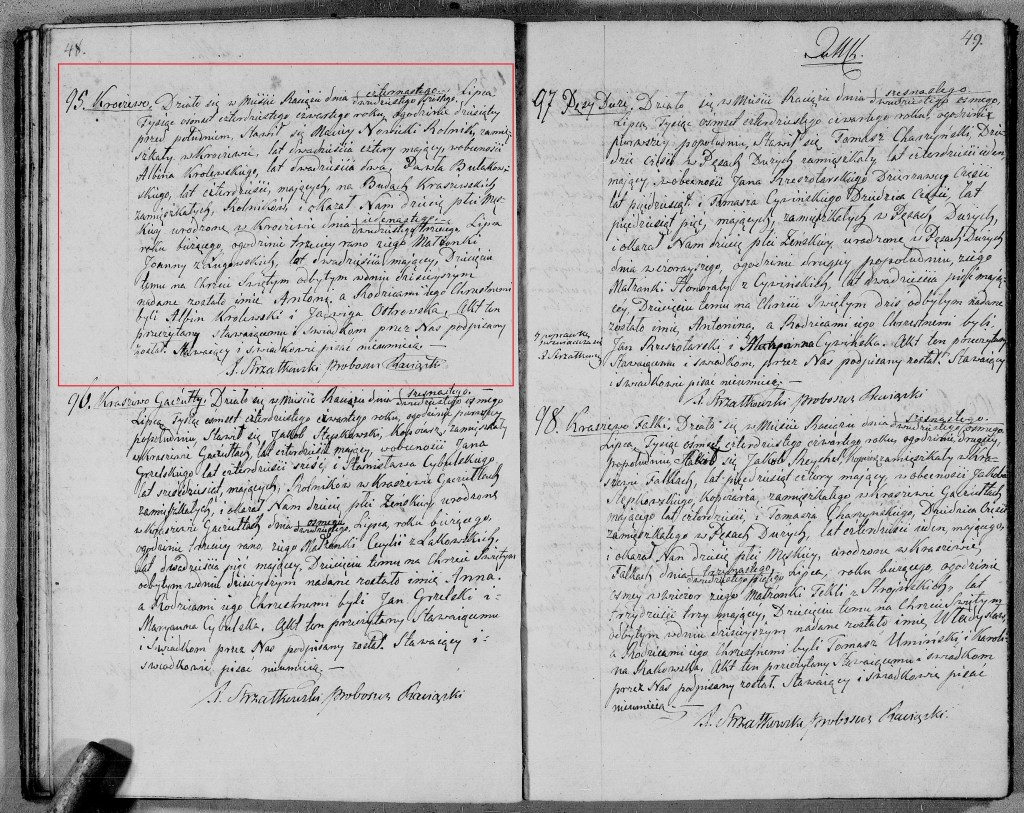

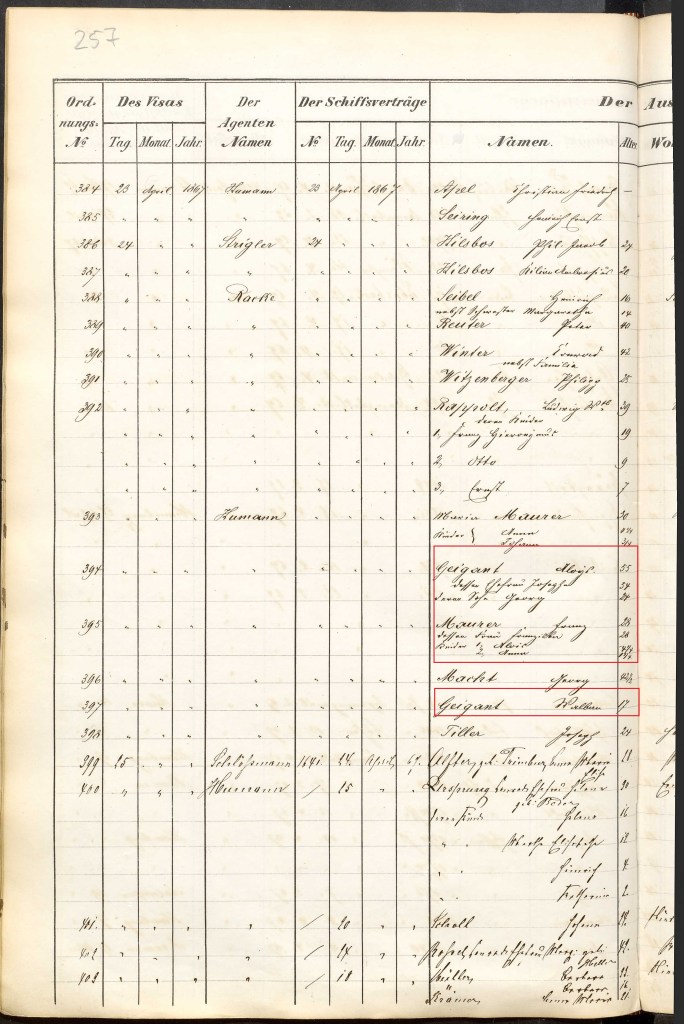

It’s always good to get more than one piece of evidence for place of origin before attempting to dive into records from Europe, and in this case, the emigration register from Mainz, Germany, provided that additional evidence (Figures 12a and b).29

Professional researcher, Marcel Elias, provided the following translation of these entries:

“Nr. 394, 24 April 1867, agent’s name Humann, Schiffsvertrag (a confirmation about booked ticket) from 24 April 1867, Names of emigrants:

Geigant Aloys, 55yo

his wife Josepha, 54 yo,

their son Georg, 24 yo

all from Waldmünchen, Bayern, Auswanderungszeugniss (approval for emigration) from Waldmünchen from 27 March 1867, heading to New York, port of departure Hamburg on April 26

Nr. 395, 24 April 1867, agent’s name Humann, Schiffsvertrag (a confirmation about booked ticket) from 24 April 1867, Names of emigrants:

Maurer, Franz, 28yo

his wife Franziska, 26 (or 28 yo)

children: Alois, 4 ¼

Anna 1 ¼

all from Waldmünchen, Bayern, Auswanderungszeugniss (approval for emigration) from Waldmünchen from 27 March 1867, heading to New York, port of departure Hamburg on April 26″

Observant readers may have noticed that there were other emigrants from Waldmünchen recorded on both the passenger manifest, as well as the emigration register. These other emigrants included group 393, consisting of 30-year-old Maria Maurer and her children, Anna and Johann, as well as 42-year-old Georg Macht. They, too, belong to the Maurer-Geigand FAN Club, and I was not surprised to discover that Maria and Georg were married at St. Boniface on 18 June 1867, less than two months after they arrived in Buffalo.30 Ship-board romance or marriage of convenience? Who knows?

Step 4: Seek Evidence for Murre/Maurer Family in Records from Waldmünchen

Unfortunately, my own ancestors, Joseph and Walburga Murre, were not found in the database of Mainz, Germany, emigration registers, which suggests that they registered in another administrative center. (They also departed from Bremen, rather than Hamburg.) So, these two pieces of evidence—the passenger manifest and the emigration register—are my best hope for tracking down my Murre family. You may also note that Ancestry indexed the last place of residence of the emigrant Maurer-Geigand clan as “Waldmühlen,” rather than “Waldmünchen,” based on the “Wohnort” column. However, the place was clearly recorded as Waldmünchen in the “Legitimationen” column in Figure 12b. This discrepancy might be concerning, apart from the fact that I also happened to find a Buffalo Evening News article from 1933 about the 60th wedding anniversary of Joseph and Anna (Pongratz) Geigand, which states that Joseph Geigand was born in Waldmünchen, Bavaria, Germany, and came to the U.S. in 1871.31 Do I know how Joseph Geigand is related to my family at this point? Heck no. Nonetheless, FAN principles would suggest that he’s got to be a part of the Maurer-Geigand FAN Club, and at this point, that’s good enough for me.

Finding my Murre family in records from Waldmünchen sounds pretty straightforward, but it’s not a slam-dunk. It may be that the Maurers were approximating their place of origin to Waldmünchen, when in fact they were from some smaller village in the vicinity. We won’t know until we try. However, trying is not something I can do on my own. FamilySearch has no scans online for Roman Catholic records from Waldmünchen, nor am I sufficiently proficient in my ability to read German. Church records from Waldmünchen are at the Bischöfliche Zentralarchiv Regensburg (diocesan archive in Regensburg), which is an archive that’s quite familiar to Marcel Elias, the professional researcher I mentioned previously. So, I handed the ball off to Marcel, and I’m awaiting his results with bated breath. Stay tuned.

Sources:

1 1900 U.S. Census, Erie County, New York, population schedule, Buffalo Ward 25, Enumeration District 222, Sheet 2A, Erie County Almshouse, line 16, Joseph Murri; digital image, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/ : 12 July 2022), citing Family History Library microfilm no. 1241033, original data from National Archives and Records Administration publication T623, 1854 rolls.

2 1870 United States Federal Census, Erie County, New York, population schedule, Buffalo Ward 7, page 73, family no. 603, Joseph Murri household; digital image, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/ : 12 July 2022), citing NARA microfilm publication M593, roll 934 of 1,761 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d; Family History Library Film no. 552433.

3 1880 United States Federal Census, Erie County, New York, population schedule, Buffalo city, Enumeration District 147, sheet 12D, family no. 120, Joseph Murry household; digital image, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com : 12 July 2022), citing NARA microfilm publication T9, roll 830 of 1,454 rolls, Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29, National Archives, Washington, D.C., Family History microfilm no.1254830; and

New York State Department of Health, Division of Vital Statistics, Death Certificates, no. 2064, Anna Mertz, 29 March 1936; Buffalo, New York, City Clerk, 1302 City Hall, 65 Niagara Square, Buffalo, New York; and

1900 U.S. Census, Erie County, New York, population schedule, West Seneca, Enumeration District 264, Sheet 28A, line 10, John Murra in Alois Klug household; digital image, Ancestry (http://search.ancestry.com : 12 July 2022), citing National Archives and Records Administration, 1900. T623, roll 1034 of 1854 rolls, FHL microfilm no. 1241034.

4 Manifest, SS Hansa, arriving 3 April 1869, lines 38-42, Muri family; imaged as “New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957,” database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/ : 12 July 2022); citing Microfilm Serial M237, 1820-1897; Line 42; List no. 292.

5 St. Boniface Roman Catholic Parish Records,142 Locust St. Buffalo, New York, microfilm publication, 2 rolls (Buffalo & Erie County Public Library : Western New York Genealogical Society, 1982), Roll 1: Baptisms (1849-1912), 1869, no. 542, baptismal record for Josephina Muri; and

Ibid., 1872, no. 977, baptismal record for Aloisius Joseph Muri; and

Ibid., 1876, no. 90, baptismal record for Francisca Walburga Murrÿ.

6 Ibid., 1886, baptisms, no. 124, record for Walburga Barbara Murry. Although it was recorded among the baptisms, the text makes it clear that this is a death record. “Walburga Barb. Murry. no. 124. Die 18a Sept. Walburga Barbara Murri quinqueqinta duos annos nata animam Deo reddidit confesso atque Viatico refecta die 20a b.m. rite sepultum est ejus corpus. Ferdinand Kolb.”; and

United German and French Cemetery Roman Catholic Cemetery, Mount Calvary Cemetery Group (500 Pine Ridge Heritage Boulevard, Cheektowaga, New York) to Julie Szczepankiewicz, Murre/Maurer/Geigand burial data, including record of lot owners for Lot 66, Section S; diagram of plot, and record of burials on lot; burial records for Walburga Barb Murri (1886) and Joseph Murre (1905).

7 Ibid., and

1900 U.S. Census, record for Joseph Murri.

8 1880 United States Federal Census, Erie County, New York, population schedule, Buffalo city, Enumeration District 147, page 31C, family no. 305, Frank Maurer household; digital image, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/1716337:6742 : 12 July 2022), citing NARA microfilm publication T9, roll 830 of 1,454 rolls, Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

9 Manifest, SS Victoria, departing 1 May 1867 Hamburg to New York, p328, nos. 46-49, Franz Maurer family (indexed as Fraz); imaged as “Hamburg Passenger Lists, 1850-1934,” Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com : 12 July 2022), citing Staatsarchiv Hamburg; Hamburg, Deutschland; Hamburger Passagierlisten; Volume: 373-7 I, VIII A 1 Band 021 A; Page: 327; Microfilm No.: K_1712.

10 “New York Births and Christenings, 1640-1962”, database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FDT1-CXT : 12 July 2022), Joseph Maurer, born 18 August 1867; and

Ibid., Michael Maurer, born 21 July 1869.

11 Ibid., Joannes Aloisius Maurer, born 2 February 1872; and

Ibid., Franciscus Maurer, born 2 February 1872.

12 United German and French Cemetery Roman Catholic Cemetery, record of burials for Lot 66, Section S.

13 “New York Births and Christenings, 1640-1962”, database, Franciscus X. Maurer, born 26 June 1873; and

Ibid., Henricum Aloysium Mauerer, born 14 July 1876.

14 Ibid., Francisca Maurer, born 19 August 1880.

15 Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/79956024/franziska-mauerer : accessed 12 July 2022), memorial page for Franziska Mauerer (28 Feb 1838–15 Apr 1881), Find a Grave Memorial ID 79956024, citing United German and French Cemetery, Cheektowaga, Erie County, New York, USA ; Maintained by Phyllis Meyer (contributor 47083260).

16 “New York Marriages, 1686-1980”, database, FamilySearch ( https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:F6S7-SJ6 : 12 July 2022), Franciscus Maurer and Francisca Schable, 22 August 1881.

17 1880 U.S. Census, Erie County, New York, mortality schedule, Buffalo city, Enumeration District 141, sheet 1, line 19, Frank Schabel, died April 1880; imaged as “U.S., Federal Census Mortality Schedules, 1850-1885,” Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/ : 12 July 2022), citing New York State Education Department, Office of Cultural Education, Albany, New York; Archive Roll No. M10.

18 1880 United States Federal Census, Erie County, New York population schedule, Buffalo city, Enumeration District 141, Sheet 93A, household no. 249, Francis (sic) Schabel household; digital image, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/ : 12 July 2022), citing NARA microfilm publication T9, roll 829 of1,454 rolls.

19 Roman Catholic Church, Our Lady of Lourdes parish (Buffalo, Erie, New York, USA), Marriages, 1883-1907,1903, no. 22, Joannes C. Bauer et Rosa K. Maurer, 17 June 1903; digital image, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G928-9NHL : 12 July 2022), “Church records, 1850-1924,” Family History Library film no. 1292741/DGS no. 4023115, image 1048 of 1740.

20 “New York Marriages, 1686-1980”, database, Franz Maurer and Matilda Grenz, 24 January 1888.

21 City of Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, Death Index, 1885-1891, p. 486, Marer, Frank, unknown date (bet. 1885-1891), Vol. 10, p 62; digital image, Internet Archive (https://archive.org/ : 12 July 2022), image 549 of 990.

22 “New York Births and Christenings, 1640-1962”, database, Joseph Maurer, born 15 January 1889; and

“U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007,” database, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/ : 12 July 2022), Matilda Catherine Maurer, born 30 April 1891, SSN 058342914; and “New York Births and Christenings, 1640-1962”, database, Martinam Maurer, born 30 April 1891. Matilda’s baptismal record identifies her as Martina, with the same date of birth, but I believe they are the same individual.

“New York Births and Christenings, 1640-1962,” database, Johannem Maurer, born 21 December 1892; and

“New York Births and Christenings, 1640-1962”, database, Elleonoram Maurer, born 22 January 1897.

23 Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/79897696/frank-x-maurer : accessed 12 July 2022), memorial page for Frank X. Maurer (1839–1910), Find a Grave Memorial ID 79897696, citing United German and French Cemetery, Cheektowaga, Erie County, New York, USA ; Maintained by DPotzler (contributor 47357059).

24 Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/79896453/matilda-r-maurer : accessed 12 July 2022), memorial page for Matilda R. Grenz Maurer (1853–19 Mar 1924), Find a Grave Memorial ID 79896453, citing United German and French Cemetery, Cheektowaga, Erie County, New York, USA ; Maintained by DPotzler (contributor 47357059).

25 St. Boniface Roman Catholic Parish Records,142 Locust St. Buffalo, New York, 1876, no. 90, baptismal record for Francisca Walburga Murrÿ.

26 Ibid., 1869, no. 542, baptismal record for Josephina Muri.

27 United German and French Cemetery Roman Catholic Cemetery, record of lot owners and record of burials on Lot 66, Section S.

28 Manifest, SS Victoria, families of Franz Maurer and Alois Geigant.

29 “Mainz, Germany, Emigration Register, 1856-1877,” database and images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/ : 12 July 2022), Franz Mauer family (Ordnungs no. 395), Aloys Geigand family (Ordnungs no. 394), and Walbur Geigand (Ordnungs no. 397), Auswanderungszeugniss [approval for emigration] from Waldmünchen from 27 March 1867, schiffsverträge [shipping contract] 24 April 1867, citing Auswanderungsregister 1856-1877, Stadtarchiv Mainz, Germany, Serial no. 395, Identification no. 1632, reference no. 70 / 1358.

30 “New York Marriages, 1686-1980,” database, Maria Maurer and Georgius Macht, 18 June 1867.

31 Buffalo Evening News (Buffalo, New York), 21 April 1933 (Friday), p 21, col 2, “Married 60 Years,” anniversary announcement for Joseph and Anna (Pongratz) Geigand,” digital image, Newspapers (https://www.newspapers.com/ : 12 July 2022).

© Julie Roberts Szczepankiewicz 2022